|

Concern over historic wetlands loss led to a national goal of no net loss (NNL) of wetlands acres and their environmental services. In support of the NNL goal, the US Army Corps of Engineers (Corps), under authority granted by Section 404 of the Clean Water Act, reviews permits to discharge fill material into wetlands. A permit review process called sequencing requires a permit applicant (permittee) to first demonstrate to a regulator that they have applied all practical means to avoid and minimize the filling in of wetlands areas as part of a development project. Then the NNL goal requires permittees to provide replacement wetlands — ecologically successful restoration of former or degraded wetlands or creation of new wetlands from uplands — to offset the adverse environmental effects of the permitted wetlands filling (see Shabman, Stephenson, & Shobe, 2002, for a discussion of offset programs in air and water pollution control programs).

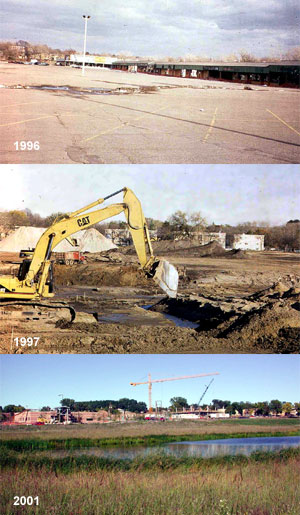

When the replacement requirement was first established, permittees were expected to provide replacement wetlands (or wetlands "credits") that were similar to the types of wetlands filled ("in-kind"), and that were located on or adjacent to the area of the fill ("on-site"). However, over time, program evaluations consistently found that inferior wetlands restoration and creation practices often were employed by permittees who had little skill (or interest) in wetlands restoration. Even when state-of-the-art practices were applied, the on-site and in-kind requirement often prohibited long-term ecological success, especially for replacing lost habitat services (e.g., wetlands hydrology was compromised by surrounding development). Meanwhile, because limited agency resources for monitoring and enforcement had to be scattered among many small wetlands credit projects, the quality of the credits was not assured; in fact, some required credit projects were never undertaken. These problems motivated interest in new approaches — generally called "wetlands mitigation banking" — for securing ecologically viable credits. One approach to mitigation banking relies on third parties (neither the regulator nor the permittee) to produce wetlands credits that can be used as offsets. Third-party wetlands mitigation banking often has been cited as a successful application of market-like environmental policy. After reviewing the experience with wetlands mitigation banking, we will conclude with a comment on whether this regulatory innovation fits the definition of market-like environmental policy.

Mitigation Banking in Brief

The single-user wetlands mitigation bank leaves the responsibility for credit production with the permittee. Under this mitigation option, a large land developer or a state Department of Transportation that expected to receive multiple future permits develops one large credit project in advance of and located away from ("off-site") their anticipated fills. The credits, once certified by the Corps, are deposited into a "bank account" that is drawn upon as future fills are permitted. The off-site location and large size of these credit projects increases the chance of ecological success and allows the Corps to better target its limited monitoring and enforcement resources.

Cases where investment in a single-user wetlands bank was not an option because of the small size of wetlands fills (e.g., parts of an acre) or the infrequent nature for a user led to the development of fee-based programs. In a fee-based program, permittees pay a fee to a third party, certified by the Corps, who produces wetlands credits in one or more off-site locations. Once the fee is paid, the third-party provider accepts financial and legal responsibility for the success of the credits. In an in-lieu fee (ILF) program, wetlands credit production occurs when a new project is initiated, while in a cash donation program the fees are used to expand an ongoing wetlands restoration project beyond its original scope. In either case, credit production does not begin until adequate funds are collected. Because fee-based providers are typically government agencies or nongovernmental conservation organizations that have the mission of wetlands restoration and creation, there is some confidence in the quality of the credits that will be produced. Nevertheless, fee-based programs have been criticized for inadequate credit production practices and for setting fees that either may not recover the costs of producing credits, or that may be so high that they discourage use of the program. Also, there is a temporal loss of wetlands acres and services while sufficient fees are being accumulated (see Scodari & Shabman, 2001, for a review of in-lieu fee programs).

Fee-based programs established a precedent for transferring legal and financial responsibility from permittees to third-party credit providers in return for cash payments. That precedent generated incentives for the development of commercial wetlands mitigation banks in which private entrepreneurs make investments in wetlands credit production and then earn a return on those investments by selling the resulting credits to permittees. In developing federal guidance for certification and use of commercial wetlands banks, regulators faced a tension between ensuring high-quality credits and the financial viability of commercial wetlands bankers. The former could be guaranteed by requiring wetlands credits to be produced and certified before they could be sold. However, it may take five or more years before ecological success can be fully judged, and a private investor typically cannot wait that long to begin accumulating returns. Thus, commercial wetlands banks were allowed to engage in limited "early" credit sales (i.e., before the credits have been certified as fully successful) in return for the posting of financial assurances that would be released when credit success was assured. This compromise facilitated the development and use of commercial wetlands mitigation banks that have produced high-quality credits and reduced time lags for securing offsets.

Regulatory Conditions and Commercial Mitigation Banking

Currently, commercial wetlands banks provide only a relatively small fraction, perhaps 10-20%, of all wetlands credits, and there are very few areas where robust credit markets have developed. This situation can be traced to the rules governing when wetlands permits are required and the separate certification rules for commercial wetlands banks that raise costs of credit production and create demand uncertainty.

First, consider investor costs. In addition to investment costs, there are considerable administrative costs to becoming certified as a commercial wetlands bank; the approval process may stretch over several years. These costs and time delays serve as barriers to entry and must be added to credit prices when a prospective banker does successfully navigate the certification process. These increased costs restrict supply of salable credits and at the same time reduce the quantity of credits likely to be demanded by permittees. (For a discussion of these and other regulatory conditions on credit prices, see Shabman, Scodari, & Stephenson, 1998.)

A number of factors work together to create significant credit demand uncertainty. There is market uncertainty about whether future land development in an area will intersect with wetlands and thus require fill permits. But even when permit demand can be predicted, the credit requirements that will be placed on permittees — and the resulting demand for credits — is highly uncertain. In fact, regulatory factors are the greatest source of wetlands credit demand uncertainty. Perhaps most important, the sequencing process continues to give regulatory preference for on-site credits. Only after regulators have determined that on-site credit production is impractical or environmentally undesirable can credits from a third-party credit provider be used as wetlands credits. Then, commercial wetlands banks often must compete with ILF and cash donation programs that do not have equivalent regulatory approval or upfront investment costs. For example, ILF and cash donation programs are not typically required to post financial assurances and do not need to reflect the opportunity cost of capital in credit fees, because they accumulate funds before they undertake credit production. The result is that permittees will favor fee-based credit options over commercial wetlands banks when those alternatives are available. Finally, uncertainty about the future of the regulatory program contributes to credit demand uncertainty. For more than 30 years, administrative and court decisions have rearranged the basic structure of the federal permit program. These changes include matters as basic as what constitutes wetlands, what constitutes fill, and what types of fills are significant enough to warrant sequencing review. These shifting regulatory principles create uncertainty about future permit demand as well as the kinds of credits that may be required or allowed as offsets.

Nonetheless, some commercial wetlands credit production has occurred in many areas of the county since the mid-1990s, indicating that the private sector will provide up-front capital for wetlands credit production if there is an opportunity to profit from such investments. Explicit or tacit understandings with prospective permittees and regulators have offered reasonable assurances that there would be a demand for some of the credits produced, and the allowance for early credit sales (with financial assurances) has helped to ensure a competitive return on investments. It is in such situations that commercial wetlands banks have developed. But, as noted, the amount of credits now supplied by commercial wetlands banks is small relative to other mitigation options, and there are very few areas with multiple commercial wetlands banks competing for business. Moreover, commercial wetlands banks must set credit prices to recover not only the costs of credit production but also the costs of gaining bank certification and the risk costs associated with future demand uncertainty. As a result, the credit prices charged by commercial wetlands banks may exceed what many permittees are able to pay.

A New Form of Mitigation Banking

The private sector has demonstrated the capacity to provide quality-assured wetlands credits, in advance of fill impacts, for use as offsets. To tap this potential of the private sector and to assure that credit prices paid by permittees reflect the full cost of credit production, a new form of mitigation banking is being discussed and developed. Called a credit resale program, the approach is now in the early stages of application in the North Carolina Ecosystem Enhancement Program (NCEEP). For a further description of the NCEEP, see Shabman and Scodari (2004).

Three interrelated components characterize a wetlands credit resale program. First, funds to capitalize the program are provided to a government agency that has the mission of securing wetlands credits for permitted fills. Second, that agency uses some of the funding for planning to predict the near-term wetlands credit needs of permittees by type and location. Third, the mitigation agency is given the authority to act as both a purchaser and reseller of credits. In that role, the agency uses a competitive bidding (Request for Proposal or RFP) process to build an inventory of quality-certified credits from private sector suppliers. The bidding process can encourage vigorous competition among wetlands credit providers on both quality and price. The winning bidders immediately begin credit production and are paid by the agency on a defined schedule tied to credit development milestones, the posting of financial assurances, and the attainment of performance criteria. The RFP stipulates credit certification requirements, and the defined payment schedule eliminates credit demand uncertainty, for the winning bidders. The agency then resells the wetlands credits it has purchased to future fill permittees at prices that recover the full costs of securing the credits. As the credit inventory is depleted, new RFPs are issued. If properly designed and administered, this approach can secure the supply, quality, and price advantages of a competitive market for wetlands credits (numerous credit sellers competing for the business of permittees).

Experience to date with the NCEEP wetlands credit resale program suggests two design considerations for helping such a program work as envisioned. First, the RFP application process can be costly, although not as costly as the process for getting certified as a commercial wetlands bank. Over time, qualified credit suppliers will need to be the winning bidders on some number of RFPs, or they will not be able to remain in the credit provision business. Thus, the credit resale program will need to issue a significant number of RFPs and then spread the work in some fashion among qualified bidders. However, there will not be enough permitted wetlands fills in one place to assure this result. Extending the program to providing other forms of mitigation credits (e.g., stream restoration, nutrient reduction, etc.) required by different pollution control programs could add to the number of RFPs issued in any year. Also, expanding the wetlands credit resale program concept regionally and across the nation could increase the likelihood that multiple credit providers would be able to prosper.

Second, wetlands offset requirements, and the resulting RFPs for wetlands credits, should be defined in terms of categories of wetlands services (that include hydrology, water quality, and habitat) rather than in terms of the wetlands asset (i.e., wetlands area and aggregate services). The water quality and hydrologic services of wetlands are watershed-location dependent, and if lost to a permitted fill, often must be replaced on or nearby the fill site. However, the values of wetlands habitat services to people and wildlife are less site-dependent, and since wetlands habitat services that are replaced on-site can often be compromised by surrounding development, these services are better secured at off-site locations. In the current wetlands mitigation program, a continuing tension over which services to favor has led to the requirement that wetlands credits be located in the same (usually small) watershed area as the fill permits. However, limiting the location of credits to small watersheds has led to thin markets in wetlands commercial banking (often only one certified bank in many areas). A similar problem would confront a credit resale program in which the RFP process was focused on a very limited geographic area, because this would constrain the possible sites in a watershed where land is suited for a winning wetlands project. As the availability of suitable lands for credit production becomes more limited, it is less likely that competition for credit contracts can be fostered. If offset requirements were stated in terms of wetlands services rather than for the wetlands asset, then a credit resale program could issue RFPs for wetlands habitat services at larger eco-region scales. This would increase the pool of land parcels that would be suitable sites for credit production, thus making for more robust competition for credit supply contracts.

If the wetlands credit resale approach was used to secure offsets for only the habitat services lost to permitted fills, regulators would still need to secure offsets for any lost hydrologic and water quality services. In determining any needed offsets for site-dependent hydrologic and water quality services, regulators would appropriately consider whether nonwetlands alternatives required by other regulatory programs could provide the necessary offsets. Site design changes (e.g., low-impact development), stormwater ponds, pervious pavement, riparian buffers, and a host of other methods can be substitutes for the water quality and hydrologic services of wetlands and can be implemented on or near the sites of permitted fills. A variety of local and state regulatory programs currently require actions to mitigate for the hydrologic and water-quality effects of land development. Recognition of nonwetlands programs would require wetlands regulators to coordinate with the relevant nonwetlands programs. The responsibility for assuring this coordination could fall to the mitigation agency charged as the credit reseller. (See Scodari & Shabman, 2001, for further discussion of the logic of this approach.)

Discussion

Commercial wetlands mitigation banking and ILF programs are often cited as examples of market-like environmental policy. The reasons for this perception are understandable. A discharger releases a pollutant (fill) into the environment (wetlands) and in turn must pay a price (credit fee) to make that discharge. This appears to be an application of the market-like concept of an effluent discharge fee. Or the permittee must bear the cost of securing an offsetting credit (a manufactured wetland) from another entity, so the NNL goal is met if they make a discharge. This appears to be an application of market-like concepts of cap and trade.

However, the reality does not match the perception. Wetlands mitigation requirements and mitigation credit options are not examples of market-like programs. The polluters (permittees) do pay when they make a discharge, but the discharger does not have discretion on when it is in their interest to avoid the wetlands and when it is in their interest to pay the fee (bear the cost of an offset) and make the discharge. Regulators require permit applicants to do everything the regulator deems practical to avoid wetlands impacts, and regulators determine what kind of offsets will be required and where they can be located. In this regard, the wetlands offset program is like any other offset program. Regulatory reviews drive the permittee towards zero discharge, and then require offsets for the discharges that remain. Wetlands offset requirements are thus best understood as a permit condition tied to a traditional command and control regulatory program.

As with other offset programs, regulators need to have offsets available in a timely fashion and in sufficient quality and quantity to meet the environmental goal — in this case, NNL of wetlands. It was in seeking to meet these needs that the wetlands mitigation program has experimented with different forms of wetlands mitigation banking — some of which have been understood as drawing on the logic of markets. Certainly encouraging private investors to compete for the right to sell wetlands credits is an application of a market-like idea. In the case of commercial wetlands banking, there is a perception that credit prices are being set by a competitive buying and selling. They are not. And it might seem logical that ILF rates are tied to a market price from a competitive credit sales program. They are not.

The wetlands credit resale program is an emerging idea that can use competitive bidding to meet the particular challenge of securing offsets for the wetlands regulatory program. However, unless permittees make the choice about when it is best to avoid making the discharge and when it is best to make the discharge and buy wetlands credits, the wetlands regulatory program should not be viewed as an application of market-like environmental policy. This observation is not offered as a recommendation to change the current practice of wetlands permitting. It is only offered to make the point that applications of market-like environmental policy are rare; at times, what appears to be a market-like policy may not be that at all. That said, as the wetlands credit resale idea suggests, the benefits of competition — certainly an idea derived from the logic for markets — still has much to contribute to the design of wetlands mitigation programs.

For More Information

Scodari, P., & Shabman, L. (2000). Review and analysis of in-lieu fee mitigation in the CWA Section 404 Permit Program. Fort Belvoir, VA: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Institute for Water Resources. Available on the World Wide Web: http://www.iwr.usace.army.mil/iwr/pdf/IWRReport_ILF_Nov00.PDF.

Scodari, P., & Shabman, L. (2001). Rethinking compensatory mitigation strategy. National Wetlands Newsletter, January-February, pp. 3-5.

Shabman, L., Stephenson, K., & Scodari, P. (1998). Wetlands credit sales as a strategy for achieving no net loss: The limitations of regulatory conditions. Wetlands, 18(3), 471-481.

Shabman, L., Stephenson, K., & Shobe, W. (2002). Trading programs for environmental management: Reflections on the air and water experience. Environmental Practice, 4,153-162.

Shabman, L., & Scodari, P. (2004). Past, present, and future of wetlands credit sales (Discussion Paper 04-48). Washington, DC: Resources for the Future. Available on the World Wide Web: http://www.rff.org/Documents/RFF-DP-04-48.pdf.

|

|

Other articles in this theme:

|

|