According to U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates, approximately 48 million Americans become ill from foodborne diseases each year; 3,000 of these cases are fatal (CDC, 2018). In response, the U.S. Congress approved the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) on January 4, 2011, which gave the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) unprecedented powers to prevent, rather than react to, future foodborne outbreaks. Regulations concentrated on the “five recognized pathways of contamination,” specifically water, soil amendments, animals, equipment/building sanitation, and worker health and hygiene.

The FSMA includes several rules, but two are of particular interest to stakeholders in the specialty crop industry, especially direct marketers, as these science-based standards cover produce that is normally consumed in its raw state, such as lettuce, apples, and berries. The Produce Safety Rule targets all farms that grow produce. The Preventive Controls Rule targets facilities that process human food but could potentially impact direct-marketing produce farms that participate in processing activities such as drying fruit. After the passage of FSMA, these rules were published online to allow for public comments, which were then incorporated into the final regulations. The Preventive Controls Rule was officially passed in October 2015 and the Produce Safety Rule in January 2016.

In accordance with a congressional mandate, the original FDA publication of the Produce Safety Rule contained a qualified exemption for small, direct-marketing farms, where small was defined as having less than $500,000 in gross sales. The published rules proposed an additional exemption for all “very small farms,” defined as those with food sales of less than $25,000. Small, exempt farms were also given a longer timeline in which to meet the less burdensome labeling standards required of them. Under the proposed Preventive Controls Rule, very small businesses, with sales under $25,000, would have until 2018 to comply with the Preventive Controls Rule and 2019 for the Produce Safety Rule, with deadlines moved up by one year for small businesses (over $25,000 and up to $250,000).

A variety of produce and small-farm organizations responded to these proposed rules with significant concerns, as direct-marketing farmers tend to have lower earnings relative to those marketing through traditional outlets (Park, Mishra, and Wozniak, 2014). First, stakeholders wanted to ensure that common direct-marketing practices, such as using products from neighboring farms in a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) operation, would not cause a farm to be reclassified as a facility (National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition, 2014). The proposed regulations also did not specifically exempt direct-marketing platforms, such as farmers’ markets, from additional facilities requirements, despite congressional intentions (National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition, 2014). Further, the gross sales used to qualify for an exemption were for all food produced, rather than just produce sales, decreasing the number of small produce operations that would be exempt. Using data from the FDA and the USDA, the Farmers Market Coalition estimated that small farms would spend 60% of their profits complying with the proposed Produce Rule regulations (Farmers Market Coalition, 2013).

When the final Produce Safety Rule was released, farms were given between two and four years to adhere to the standards, dependent on their sales. Additionally, direct-marketing farms with less than $500,000 per year in food sales would still receive a qualified exemption with reduced requirements, and all farms with annual produce sales less than $25,000 were fully exempt. Under a qualified exemption, farms must still maintain all recordkeeping elements and follow specific labeling requirements. The FDA maintained its ability to remove an exemption if there was a food outbreak investigation directly linked to the farm or the FDA found it necessary for any reason related to public health. Small businesses ($250,000–$500,000 in produce sales) would have until 2019 to comply and very small businesses ($25,000–$250,000) had until 2020. In their final Preventive Controls Rule, the FDA explicitly exempted farms that do nonfarming processing activities to sell directly to consumers, including activities such as CSAs and roadside stands.

Though the final Produce Safety Rule addressed stakeholder comments regarding compliance costs, the publication also stated that “because small farms will bear a large portion of the costs, FDA concludes that the final rule will have a significant impact on a substantial number of small entities” (80 FR 74353). Specifically, these cost estimates include $2,885 for very small farms and $15,265 for small farms (Collart, 2016), which is not insignificant given that the average direct-marketing farmer has direct-to-consumer sales of $9,063 (USDA, 2014). The closure of direct-marketing operations is problematic as direct marketing has the potential to both increase small farm incomes (Detre et al., 2011) and stimulate the local economy (O’Hara and Shideler, 2018). Certain consumers also receive benefits as they perceive locally grown produce to be of superior quality and nutrition (Onozaka, Nurse, and Thilmany McFadden, 2010). Additionally, policy makers have recognized the ability of direct marketing to increase fresh food access in underserved communities, including when Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) redemptions are allowed at farmers’ markets. As such, it is important to understand how direct-marketing farmers may react to the new FSMA regulations.

We surveyed California direct-marketing farmers on their reactions to and perceptions of FSMA, specifically their worries and possible actions they might take as a result. We recruited farmers through Local Harvest, an online database where direct-marketing farms can advertise themselves, including location and contact information. We contacted 1,187 farms in California by email in 2016 and asked for their participation in an online survey, resulting in 67 usable responses. All questions were initially piloted with direct-marketing farmers in Columbus, Ohio, and San Luis Obispo, California.

The demographics of direct-marketing respondents reflect national trends, though a greater percentage of the sample was female. Compared to the 2012 USDA Agricultural Census, 52% of the sample had one operator, relative to 49% nationwide; 51% participated in a profession other than farming, compared to 52% nationally. The USDA’s 2015 Local Food Marketing Practices Survey found that 38% of those involved in direct-marketing decisions were women, compared to 50% in the respondent sample (USDA, 2016); 13% of the sample was under 35 years of age, which is slightly larger than the USDA value of 9%.

Table 1 reports respondent beliefs regarding FSMA. For each question, we report the number of farmers who answered that question (N), as well as the percentage of those respondents that selected each response (%). Nearly 39% of the sample were not familiar with the FSMA. Survey respondents were given information about the legislation, including that it was a federal law, incorporated some degree of exemptions for direct-marketing operations, and was still in the revision process. We report results for both the total sample as well as those farmers who already knew about the regulations. Across the board, respondents generally felt that the act was unnecessary, and they were skeptical of its ability to improve food safety outcomes. Despite this, there was a reluctance to advocate for extensive exemptions, with only 36% of respondents suggesting exemptions for direct-marketing farms, relative to 61% for small farms; the values were slightly higher among farmers who were already familiar with FSMA. The average respondent defined small farms as having a gross annual sales threshold of $354,310, which is actually lower than the final FDA value of $500,000. Farmers were then asked to select all their potential concerns about, and responses to, the legislation. Farmers were most worried about compliance costs and accompanying paperwork. The most common response to FSMA was to not expand rather than reduce production.

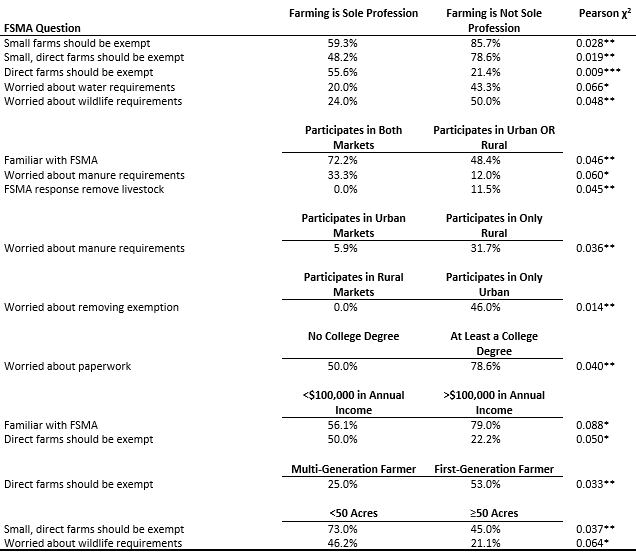

We performed subsequent analyses to better understand how different types of farmers perceived FSMA. Table 2 reports all the categories that were significantly different from each other, using Pearson χ2 tests. Farmers were first categorized by professional diversification and type of market participation. There appear to be several differences between farmers who earned income from professions other than farming and those that did not. A higher percentage of respondents whose sole profession was farming believed all direct-marketing farms should be exempt from FSMA, while a higher percentage of those who had a second profession instead suggested exemptions for only small farms and small farms that participate in direct-marketing. Additionally, those who participated in professions other than farming worried about the water and wildlife requirements at a greater rate than those for whom farming was the sole profession. A greater percentage of farmers who sold in both urban and rural markets were familiar with FSMA and worried about the manure requirements, while a smaller percentage intended to remove livestock in response to the policy, relative to farmers who sold solely in rural or solely in urban areas. This difference in concerns about manure requirements appears to be driven by rural marketers, who worried at a greater rate than those who participated in urban markets. Conversely, a greater percentage of urban marketers were worried about the FDA’s ability to remove the direct-marketing exemption.

Note: Only significantly different results are reported. *,**,*** denote significance at the 10%, 5% and

1% level, respectively.

Education also impacted farmer perceptions, as 79% of those with a college degree were concerned about the FSMA paperwork requirements, relative to 50% of those with no college degree. A greater percentage of higher-income respondents were familiar with FSMA, while a lower percentage believed that all direct-marketing farms should be exempt from the regulations. Over half of first-generation farmers believed that all direct-marketing farms should be exempt from the regulations, compared to 25% of those that came from farming families. There were slight differences between large and small farms, with a greater percentage of owners of farms less than 50 acres in size suggesting that small, direct-marketing farms should be exempt and worrying about the wildlife requirements of the bill.

The biggest takeaway is how unconcerned farmers appear to be about the FSMA, despite an overall negative view of it. Nearly 39% of the sample was not familiar with FSMA, which subsequent analysis showed did not differ by farm size, suggesting that being exempt is not an explanation for this finding. While the smallest farms have until 2020 to comply with FSMA, there is still a surprising lack of knowledge about it. Higher rates of higher-income farmers and those that sold in both urban and rural areas were familiar with FSMA, potentially because those that travel to urban markets were more likely to have higher-income operations and also be more concerned with food safety. It is also possible that urban marketing leads to increased interaction between farmers and thus information sharing, a relationship that could warrant further study. Less than 20% of the sample felt that additional food safety regulations were needed, and this belief did not differ by type of farmer; this is in line with the attitudes expressed during interviews that foodborne illness outbreaks were primarily a problem for large-scale operations.

Turning to the types of farms that should be exempt from FSMA, there was significant disagreement across farmer categories. For instance, while 61% of the total sample thought there should be exemptions for small farms, 85.7% of those that participated in other professions believed that smaller farms should be exempt. The difference between dedicated farmers and those with a second job is even starker when it comes to exemptions for small, direct-marketing farms. This result is surprising, as only 28% of those with a second profession had farms of fewer than 50 acres. Additionally, this pattern changes when it comes to direct-marketing farms of any size, where dedicated farmers were more likely to call for an exemption. While farm size had little impact on attitudes toward FSMA, a greater percentage of those with smaller farms believed that small, direct-marketing farms should be exempt. Greater rates of those that made less than $100,000 and first-generation farmers believed that all direct-marketing farms should be exempt, although 78% and 75% of them, respectively, had farms of less than 50 acres in size. In general, the preference for exemptions did not seem to be tied to respondents’ self-interest.

A greater percentage of farmers who also had other professions were concerned about water and wildlife, as were respondents with smaller operations, perhaps because those aspects are harder to monitor for someone off the farm or with fewer resources. Rural marketers were more worried about manure requirements, urban marketers about the FDA’s ability to remove exemptions, and college graduates about paperwork, demonstrating the disparate ways in which this legislation could impact direct-marketing farms.

Overall, it would appear that direct-marketing farmers have concerns about the proposed regulations and expect to either reduce or not expand their operations as a result. The finding that nearly 40% of the sample was unfamiliar with the regulation highlights the need for increased information availability, with an emphasis on the relevant requirements and paperwork expectations. This is an excellent opportunity for collaborations with extension and outreach coordinators as the compliance dates for these operations near (between 2019 and 2020 for qualified exempt farms).

80 FR 74353. 2015. Standards for the Growing, Harvesting, Packing, and Holding of Produce for Human Consumption. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2018. “Foodborne Illnesses and Germs.” CDC Food Safety. Available online at https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/foodborne-germs.html.

Collart, A.J. 2016. “The Food Safety Modernization Act and the Marketing of Fresh Produce.” Choices 31(1): 1–7.

Detre, J., T. Mark, A. Mishra, and A. Adhikari. 2011. “Linkage between Direct Marketing and Farm Income: A Double-Hurdle Approach.” Agribusiness 27: 19–33.

Farmers Market Coalition. 2013. “On Food Day, Stand Up for Your Farms and Food!” Available online at https://farmersmarketcoalition.org/on-food-day-stand-up-for-your-farms-and-food/.

National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition. 2014. “Direct Marketing.” Available online at http://sustainableagriculture.net/fsma/who-is-affected/direct-marketing/.

O’Hara, J.K., and D. Shideler. 2018. “Do Farmers’ Markets Boost Main Street? Direct-to-Consumer Agricultural Production Impacts on the Food Retail Sector.” Journal of Food Distribution Research 49(2): 19–37.

Onozaka, Y., G. Nurse, and D. Thilmany McFadden. 2010. “Local Food Consumers: How Motivations and Perceptions Translate to Buying Behavior.” Choices 25(1): 1–6.

Park, T., A.K. Mishra, and S.J. Wozniak. 2014. “Do Farm Operators Benefit from Direct to Consumer Marketing Strategies?” Agricultural Economics 45(2): 213–224.

Ribera, L.A., F. Yamazaki, M. Paggi, and J.L. Seale Jr. 2016. “The Food Safety Modernization Act and Production of Specialty Crops.” Choices 31(1):1–7.

Uematsu, H., and A.K. Mishra. 2011. “Use of Direct Marketing Strategies by Farmers and Their Impact on Farm Business Income.” Agricultural and Resource Economics Review 40(1): 1–19.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2014. Farmers Marketing. 2012 Census of Agriculture Highlights ACH12-7. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service, August.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2016. Direct Farm Sales of Food: Results from the 2015 Local Food Marketing Practices Survey. 2012 Census of Agriculture Highlights ACH12-35. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service, December.