The fair trade movement was created to promote the ethical exchange of goods from production to shelf. At its core, fair trade is meant to benefit the producers; typically, the poorest farmers and laborers in developing countries. Although some critics argue that the system may cause more damage than good, producers who adhere to fair trade guidelines generally receive higher compensation than if they were to sell in conventional markets. Fair trade supply chains tend to be shorter, and consumers who purchase fair trade products typically pay more than for conventional substitutes (Nelson and Pound, 2009). To qualify for fair trade certification, producers must meet standards managed by private third party certification organizations. These standards vary, based on the product, region, and third party system in ways that might not be fully understood by consumers.

Source: Fair Trade Annual Report (FLO-I).

Various Years

The fair trade certification industry is complex. Dozens of certifying bodies are responsible for labeling claims. The largest governing body is The Fairtrade Labeling Organizations International (FLO-I), which serves as an umbrella organization for several groups. In 2012, the main North American member—Fair Trade USA—left FLO-I to pursue its own standards. This impacted FLO-I and perhaps the United States and Canadian markets—but in which ways?

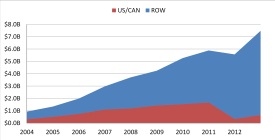

Total global fair trade sales have been increasing. In 2011, global retail sales topped $6.7 billion, an eight-year compound annual growth rate of ~25% (Figure 1). While the United States and Canada accounted for sales of more than $1.7 billion in 2011, this is still a relatively under-developed market compared to the EU. In 2011, before Fair Trade USA left FLO-I, the U.S. market share was 25% compared to the EU's 65% (FLO-I Annual Report). For the first time, 2012 saw a decline in the value of FLO-I-certified sales as Fair Trade USA increased its share of the market.

Mintel’s Global New Product Database (www.gnpd.com) reports food and beverage product innovations launched globally. Of the 3,227 fair trade-certified products from 1999-2012, 632 (20% of the global total) were launched in the United States and Canada compared to 2,595 across 40 other countries (Rest of the World (ROW), Figure 2).

The top two fair trade categories in both the United States/Canada and the ROW are the same; combined, hot beverages and chocolate confectionery account for nearly 60% of all certified food and beverage innovations. Tea and coffee typically consist of a single (hot beverage) ingredient sold in a semi-processed form at the consumer level. Chocolate bars and powders contain multiple ingredients, but the majority of the product value comes from the cocoa beans and sugar. This leads to a question of how the chocolate bar contents of cocoa and sugar (imported fair trade ingredients) as opposed to dairy (domestic ingredients) are separated and covered by more complex fair trade standards, processing requirements, and label claims.

| U.S./Canada | ROW | |||

| Organic | 469 | 38.80% | 1359 | 50.10% |

| Kosher | 267 | 22.10% | 105 | 3.90% |

| Environment | 179 | 14.80% | 490 | 18.00% |

| All-Natural | 74 | 6.10% | 59 | 2.20% |

| Premium | 73 | 6.00% | 236 | 8.70% |

| Vegan | 62 | 5.10% | 76 | 2.80% |

| Charity | 53 | 4.40% | 96 | 3.50% |

| Vegetarian | 25 | 2.10% | 257 | 9.50% |

| Animal | 6 | 0.50% | 37 | 1.40% |

| TOTAL | 1208 | 100% | 2715 | 100% |

Fair trade products are typically connected to several other agricultural issues such as social, ethical, or environmental aspects of sustainability (Arnould, Plastina, and Ball, 2009).

In order to communicate these and to differentiate supply chains, it is common for fair trade items to use multiple positioning claims. Consumers may be interested in a subset of these topics, or to purchase by the fair trade claim alone. The nine most common claims including ethical production practices, naturalness, and religious/personal beliefs are reported in Table 1. Such claims appear to be the norm in the United States and Canada, with the 632 fair trade products making 1,208 “Fair Trade +” claims (compared to 2,715 claims for the 2,595 ROW products).

Within the U.S. and Canadian markets, organic, kosher, and environmental consciousness are the top three claims made on fair trade products. In total, they account for three quarters of all claims made. In the ROW, the top three claims are organic, environmental consciousness, and vegetarian. Over 10% more products claim to be organic in the ROW than in the U.S./Canada market. This could mean that consumers in the ROW value fair trade + organic more than U.S./Canadian shoppers. Similarly, over 22% of the claims made on U.S./Canada products were kosher compared to the ROW’s 4%. This implies that kosher holds more value in the U.S./Canada fair trade market. In several key product categories, around half of all fair trade items also make an organic claim. Yet in the United States and Canada, this is less frequent. Consider this aspect alongside the question “does organic mean local?” If consumers hold the belief that organic foods are more likely to be locally sourced, then a claim of fair trade ingredients may be misaligned with their (prior) beliefs. The United States and Canada have public organic standards with formal certification and audit procedures making the claim more rigorously managed than other nations. At the very least it is a more complex fair trade + claim, so it is interesting that it is most common.

Claims aren’t limited to one per product; more often than not, multiple claims exist on a fair trade product label. Ten percent of the U.S./Canadian fair trade products made no other claim, compared to 30% of those in the ROW. But at the other extreme, 11% of North American products (2% ROW) made four claims in addition to fair trade. These “fair trade +” claims combine a message about sourcing with other environmental, social, or ethical attributes. Multiple-claim usage can be interpreted several ways, but expansion of reach seems to be the most logical explanation from a marketing perspective. By utilizing multiple claims on a package, a firm expands its target market of shoppers. A fair trade + organic claim theoretically meets the wants of both the fair trade shopper and the organic shopper. One claim may influence the purchase, even if the other does not.

No national government controls the fair trade industry. It is a self-regulating market primarily governed by the FLO-I, which is a non-profit group that sets minimum standards for all member organizations. The FLO-I is a democratic body operated by global representatives of fair trade markets, each of whom are voted in for tri-annual terms. In the 1999-2012 timeframe, FLO-I certified a vast majority (~94%) of all food and beverage fair trade products introduced to the global market. A few smaller groups (Oxfam, Institute for Marketecology, Bio Equitable, Tradecraft, and Ecocert) are active in the certification market, mostly in the EU.

Given Fair Trade USA’s decision to end FLO-I membership and its desire to offer different ingredient and sourcing standards, the scope of the fair trade market has changed. Fair Trade USA announced a goal of doubling the impact of fair trade for farmers by 2015 through its “Fair Trade for All” program. The decision was controversial because Fair Trade USA adopted new standards that loosened certification requirements compared to FLO-I.

Fair Trade USA’s new standards increased the breadth of its producer network by allowing coffee plantations to earn certification, which are barred by the FLO-I. Critics argue Fair Trade USA made the changes to standards in the pursuit of revenue, while Fair Trade USA defends its stance as enhancing market access for a larger group of producers. Since 2012, Fair Trade USA has been the dominant fair trade-certifier in North America. In response, FLO-I is making efforts to regain market share through the formation of Fairtrade America.

Certification organizations typically enforce a “quamvis” (as much as possible) rule for multi-ingredient food and beverage products. If there is limited supply of a fair trade version of a particular ingredient, a conventional substitute can be used. Some certifiers offer adaptations of their fair trade seal to be used in this situation, notably Fair Trade USA (Figure 3). An open question is, will consumers notice the difference between a 100% fair trade product and one that is labeled as containing fair trade ingredients? Firms can choose to highlight which ingredients are fair trade. Compare this to the FLO-I which states that 100% of any ingredient that can be fair trade-certified, must be fair trade-certified. Under this standard, a chocolate bar must have fair trade cocoa and fair trade sugar. However, if FLO-I determines that fair trade milk does not have a high enough supply, a conventional form can replace it (Table 2). To further complicate the composite goods market, in 2014 FLO-I launched the Fairtrade Program Mark which recognized that “some companies…want to source 10 percent, 30 percent or even all of their overall volumes of an individual ingredient on Fairtrade terms” (Fair Trade Program Marks, 2014). This program offers businesses an alternative to creating and marketing traditional 100% fair trade-certified products. Instead, the Fairtrade Program is a sourcing initiative complete with its own certification seals (Figure 4). A company looking to ethically source ingredients sets quotas through the program and is allowed to distribute the ingredients across any number of products. In turn, these products are allowed to bear the Fairtrade Program Mark. Just as Fair Trade USA’s divestiture and adjusted standards widened its market, FLO-I is betting its Fairtrade Program will do the same. It will be interesting to see how it affects the U.S./Canada market.

| FLO-I Affiliates |

Fair Trade USA |

|---|---|

| 100% of any ingredient that can be fair trade certified, must be fair trade certified. |

100% of the ingredient commonly associated with a product must be fair trade certified. For example, a chocolate bar must contain 100% fair trade Certified cocoa. |

| Any product may carry the fair trade mark if more than 50% of its total ingredients (calculated by dry weight) are sourced from fair trade certified producer organizations. | For any individual fair trade certified ingredient used in the product, 100% of that ingredient must be certified. For example, if a product contains fair trade certified vanilla extract, all of the vanilla extract in the product must be fair trade certified. |

| If the total fair trade certified ingredient content is less than 50%, the product may still be eligible if it has one significant fair trade ingredient that represents more than 20% of the product’s dry weight. | The product must contain at least 20% fair trade certified content in total, and all ingredients that can be fair trade certified must be fair trade certified, if the ingredient is commercially available. |

| http://www.fairtrade.org.uk/what _is_fairtrade/fairtrade_certification _and_the_fairtrade_mark/ composite_products.aspx |

http://www.fairtradeusa.org /certification/producers /ingredients |

Third party certification organizations provide these types of ingredient labels for two reasons. First, these labels allow composite good food manufacturers to tap into the fair trade market. This provides opportunities for other (minor ingredient) fair trade producers (e.g., honey and vanilla). Second, such labels are an attempt to minimize consumer confusion. A unique label that claims to only have a certain amount of fair trade ingredients should be transparent. This is critical when a composite good has a very low content of fair trade ingredients. A similar process for labeling multi-ingredient organic food and beverages is now in place in the United States (Van Camp et al., 2010).

Firms in the United States and Canada are growing the number of fair trade food and beverage products launched, following a similar trend in the rest of the world. However, North America still lags behind the EU, in particular, in terms of consumption. Explorations of the demand side of consumer segmentation and behavior trends may offer some insight into this difference. Age, gender, location, and socioeconomic status are all likely determinants of an ethical/sustainable consumer. Consumer knowledge of fair trade food and beverage products and brands may be lower in the United States and Canada, suggesting the need for educational and informational campaigns. On the supply side, observation of the influence of fair trade + claims and the role of third party certification organizations are revealing and perhaps of concern if not aligned with what consumers understand fair trade to mean.

Fair trade is an emerging market in the United States and Canada, with no signs of slowing. The fastest growing categories are also the largest. The product innovation data suggest the importance of hot beverages and chocolate confectionary products. Aiding growth, a small number of fair trade wine, honey, and produce items have emerged in the North American market. However, similar to trends in the U.S. organic market, further growth will likely center on multi-ingredient items (e.g., chocolate) which do not contain 100% fair trade content. Efforts to develop supply chains to ensure a growing proportion of these ingredients are fair trade (where possible) are to be commended. Yet, transparent communication to consumers of the current state, challenges, and successes will require close attention. Broader sourcing standards, whether solely permitting cooperatives or also allowing small producer groups to be eligible to supply fair trade ingredients, is a nuanced discussion, but one likely to be important to some consumers and one where it appears certification organizations don’t yet agree.

Arnould, Eric, Alejandro Plastina, and Dwayne Ball. 2009. "Does Fair Trade Deliver on Its Core Value Proposition? Effects on Income, Educational Attainment, and Health in Three Countries." Journal of Public Policy & Marketing. 28(2): 186-201.

“Fair Trade for All.” 2014. Fair Trade USA. Available online: http://fairtradeusa.org/fair_trade_for_all.

[GNPD] Global New Products Database. (2014). Frontpage. Mintel International Group Ltd. Available from: http://www.gnpd.com/sinatra/gnpd/frontpage/.

Nelson, Valerie and Barry Pound. 2009. The Last Ten Years: A Comprehensive Review of the Literature on the Impact of Fairtrade. Natural Resources Institute, University of Greenwich, U.K. Available online: http://www.fairtrade.org.uk/resources/natural_resources_institute.aspx.

Stanton, John, Neal Hooker, and Ekaterina Salnikova. 2011. "A Comparison of Process and Ingredient Claims on US and EU Food." Romanian Distribution Committee Magazine. 3(3): pp 8-11.

The Fairtrade Labeling Organizations International. 2014. “Fair Trade Program Marks.” Available online: http://www.fairtrade.net/1065.html.

The Fairtrade Labeling Organizations International. Various Years. “Fair Trade Annual Report.” Available online: http://www.fairtrade.net/annual-reports.html.

Van Camp, Debra, Pauline Ie, Noah Muwanika, Neal H. Hooker, and Yael Vodovotz. 2010. "The Paradox of Organic Ingredients." Food Technology. November: pp. 20-29.