Tax matters for American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) farmers and ranchers have long been an issue. In recent years, however, they have surfaced as a bigger problem. The tax environment in Indian Country is underpinned by virtue of Indian lands belonging in the federal estate. The increased use of tax returns in the USDA program eligibility determination, the USDA’s targeting of a larger number of AI/AN participants, and the Internal Revenue Service’s (IRS) increased use of Form 1099 have increased the complexities that can arise for an individual AI/AN producer.

There are many factors, such as income tax exemption and land ownership, that complicate federal income and self-employment (SE) taxes for AI/AN farmers and ranchers within Indian Country (defined by 18 United States Code [U.S.C.] 1151). However these factors extend beyond just tax issues by limiting tribal producers’ access to many of the common USDA programs. For example, the Risk Management Agency’s (RMA) Adjusted Gross Revenue (AGR) and AGR-Lite programs require a federal income tax return (Schedule F) to participate, but if the AI/AN producer’s income was not subject to federal taxes, tax returns probably do not exist. Without a tax return, the producer cannot present a legally acceptable method of verifying income to qualify for the programs. Agricultural income verification through filing a Schedule F is also required for many of the other USDA agencies’ programs.

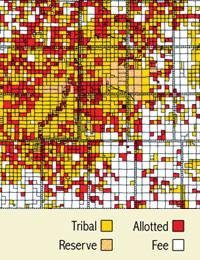

Determining precisely what income is or is not subject to taxes adds to the confusion about program eligibility and non-filing issues for AI/AN producers. In many cases, lands under the AI/AN producer’s control have different ownership, such as USDA-Bureau of Land Management (BLM), private/fee simple, or state (Figure 1). In these cases, income derived from the mix of lands will have different tax profiles. This complexity is exacerbated by not having adequate access to agricultural and tribal tax issues training for professional tax preparers working within Indian Country. In some of the more remote areas of reservations, very few options for professional tax preparation exist at all, let alone easy access to tax preparation training. There are a few exceptions. When the communities have access to either the Federally Recognized Tribal Extension Program (FRTEP) or the 1994 tribal institution with an active extension component, either can coordinate training for tribal agricultural producers or point them to other resources such as RuralTax.org, a website created by extension specialists with information on agriculture tax issues. However, the FRTEP is limited in its geographic scope to less than 30 reservations, but it is affiliated with the 1862 land-grant colleges with their long-running Extension programs. As for the 32 1994 tribal colleges, not all of them have an active Extension component so, when possible, FRTEP agents work with tribal college personnel to deliver programs.

Clear IRS guidelines are lacking on how AI/AN producers can correctly address tax-reporting requirements, including determining what income is subject to income and SE taxes. A lack of clarity surrounding these issues combined with obscure federal tax rules for income from trust lands can place AI/AN agricultural producers at both legal and financial risk.

The following sections present some of the issues associated with agricultural tax matters on tribal lands: Land Ownership, Rights and Taxes, and Form 1099 reporting and tax implications when dealing with USDA programs.

Indian land ownership has arisen from treaties, executive orders, and court decisions which distinguish it from non-Indian, fee-patent or fee-simple owned, off-reservation land. Because American Indian reservations contain land with multiple types of ownership, it is not always an easy task to determine the actual classification of each parcel of land. However, knowing the correct land classification where agricultural activity occurs is essential in understanding the potential management and taxation issues.

There are three main classes of land tenure in Indian Country: 1) tribal trust, 2) allotted, and 3) fee simple. Nash and Burke (2006) define each of these as follows. Tribal trust is land owned by either an individual Indian or a tribe, the title to which is held in trust by the federal government. Most trust land is within reservation boundaries, but trust land can also be off-reservation or outside the boundaries of an Indian reservation. Allotted land was originally outside of treaty reservations and the federal government distributed it under the Dawes (General Allotment) Act between 1887 and 1934 to individual Indians, generally in 40-, 80-, or 160-acre parcels. Similar to tribal trust lands, all of these allotments were held in trust for individuals by the United States. That is, the legal title was held by the United States and the allottee was given beneficial title—the right to live on, use, and profit from the allotment. Finally, fee simple land status is when the owner holds title to and control of the property and may make decisions about using or selling the land without government oversight. Fee simple is how land is typically held by most non-tribal agricultural producers. There is considerable fee simple land within many reservations, a result of the General Allotment Act wherein lands in excess of that allotted to individuals were declared surplus and converted to fee simple title and sold to non-Indians.

When tribal lands are co-mingled with the other types of land classes, there are legal and tax compliance issues. In cases where trust and allotted lands cross over county and state lines or when tribal agricultural activities occur on a checkerboard of types of land ownerships (Figure 1), correct handling of the agricultural operation’s tax obligations are vague with only rare clarity being provided by the IRS or courts. Recent trends only strengthen the need to address these issues including the increase in USDA programs targeting tribal producers and the growing interest in tribes’ development of farms and ranches both on and off their reservations.

Finally, each of the potential land managers (individual, tribal, city, county, state, or federal) make it difficult for Indian tribes to assert regulatory and legal control and to foster new agricultural development on their lands (Indian Land Tenure Foundation, 2012c). Land in Indian Country may also have fragmented ownership where many people own an undivided share of a particular parcel. In some cases, the land is highly fractionated having 100 or more co-owners of the same parcel of land (Goetting and Ruppel, 2009).

Indian tribes have special legal status as sovereign nations under the U.S. Constitution and, as such, they retain the power of self-government within their tribal territories (Hiller, 2005). Federal policies—such as the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 and the Indian Self-Determination and Educational Assistance Act of 1975—have reaffirmed Indian tribes’ rights to govern themselves and manage their own lands and resources. Among these rights are exemption from most state and some federal taxation for both the tribe and individuals.

The General Allotment (Dawes) Act of 1887 states that Indian allottees are to receive their allotments “free of any charge or encumbrance”; however, the IRS’ interpretation of this was very narrow. It was not until 1956 that further clarification was provided in Squire v. Capoeman, 351 U.S. 1 (1956). The courts stated that not only is Indian land exempt from taxation, but so, too, is any income “directly derived” from that land. Further, IRS revenue ruling 67-284 established five factors to be used in determining income exemption: 1) land must be held in trust by the United States; 2) land is restricted and allotted for an individual Indian, not the tribe; 3) income must be directly derived from the land, 4) the statute, treaty, or authority evinces Congressional intent that the allotment be used to protect the Indian; and 5) language of the authority indicates clear Congressional intent that the land is not to be taxed until it is conveyed in fee simple to the allottee (Nilles, 2012).

The IRS recognizes that tax issues related to tribal governments can be complex and has sought assistance from individuals and various Indian Tribal Governments (ITG) to work with the tribes on tax issues. However, it typically only works with the ITG and not individual AI/AN agricultural producers. Additionally, there are no IRS publications illustrating tax rules and conditions as to when income is exempt from income and SE taxes. IRS Publication 225: Farmer’s Tax Guide and the RuralTax.org website both discuss the tax treatment of farm income and expenses, and help both agricultural producers and their tax professionals correctly report farm income and expenses. The situation that arises when some or all of the income is exempt from taxes is more complicated and has less IRS guidance. The 2010 Tax Guide for Native American Farmers and Ranchers, published by the Intertribal Agriculture Council and USDA-RMA, attempts to provide some guidance, but in the absence of clear IRS guidance, it only states opinions.

One vague area of tax treatment is how to treat expenses related to raising an agricultural product that is further refined or processed by AI/AN agricultural producers when their farm income is already exempt. For example, if wool from a farmer’s sheep is used to create a rug to sell, can the producer deduct the value of the wool or any of the expenses of raising and shearing the sheep? One school of thought suggests that if the farmer is exempt from taxes, the farmer would not have recorded the expenses on his or her tax return and, therefore, cannot record them as expenses in rug production. This seems illogical as it would cause a farmer who is exempt to pay more income tax than a farmer who is not. The IRS cannot issue clear guidance on this point because it is not part of the Internal Revenue Code and, therefore, educational programs can only discuss options for the farmer.

The lack of records, inconsistency in how to treat tribal farm/ranch income, and uncertainty about the land ownership were all part of the lead up to a recent lawsuit between AI/AN producers and the USDA.

In 2011, a settlement was reached on the Keepseagle v. Vilsack (1999) class action lawsuit that claimed the USDA denied thousands of AI/AN farmers and ranchers the same opportunities to get farm loans or loan servicing that were given to non-Indian farmers and ranchers. The plaintiffs also claimed that the USDA did not do outreach to AI/AN farmers and ranchers or provide them with the technical assistance they needed to prepare applications for loans and loan servicing. The total settlement was for $760 million. (Keepseagle v. Vilsack Settlement, 2011).

From the settlement, qualifying class members received up to $50,000 or more and forgiveness of outstanding USDA loans. Although substantial effort was put towards explaining the settlement and getting individuals to sign up, only 5,191 individuals did so and only $340 million of the $760 million was sent out in the form of payments, taxes, and debt relief. Although there are many reasons for the low sign-up rate, anecdotal evidence suggests the sentiment among many of the AI/AN producers is that they are exempt and, therefore, do not qualify for many USDA programs or assistance, including the settlement.

Many efforts are underway to overcome the issues leading up to the lawsuit. USDA agencies such as the National Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), the Farm Service Agency (FSA), Rural Development, RMA, and the regional centers for Risk Management Education (RME) have made a concerted effort to reach out to AI/AN producers not only through educational programs, but also through grant funds programs. Although AI/AN producer participation in these programs has been improving, it still remains quite low.

For example, the NRCS Environmental Quality Improvement Program (EQIP) has a provision which allows for a 90% cost share for AI/AN producers or other socially disadvantaged producers compared to the regular rate of a 75%. Yet even with this increased cost coverage, there is reluctance by AI/AN producers to participate. In a 2009 study on the participation rates by targeted farmers, Nickerson and Hand found that although AI/AN producers qualify for the higher 90% payment rates, farms on reservations are less likely to be enrolled in EQIP than are non-reservation ones. In this study, reservations accounted for about 9.3% of the farms and 7.7% of operated farmland in comparison states, but only about 4.2% of the EQIP contracts and 6.2% of the EQIP funding.

Other agencies also have AI/AN producers and socially disadvantaged producers targeted for assistance. These include the RMA’s Outreach Assistance Program and USDA’s National Institute for Food and Agriculture’s Beginning Farmers and Ranchers Development Program. The Western RME center, in collaboration with the FRTEP agents, developed guidelines for their advisory board, assisting it in key considerations when reviewing grants from or targeting AI/AN. While all of these efforts are improving the farm and ranch management skills of the AI/AN producers, the core underlying issues of complex land ownership and tax codes remain.

In some situations, current efforts can even compound the problems. Educational programs can be conducted without a full understanding of the underlying issues and give AI/AN agricultural producers flawed guidance. Educational programs or a liaison committee can talk about FSA loan programs and what the qualifications are, but cannot fix the problem of the lack of ability to verify income through a tax return and provide land with an unencumbered, fee title as collateral.

There is currently an increased interest in farming and agriculture, as seen by the “local food” movement. This movement, coupled with strong commodity prices, has created a resurgence of agriculture in Indian Country. Programs to support agricultural activities as part of community development are being implemented and more are being considered. While this is helping to preserve and expand on Indian heritage, it is also putting increased pressure on the issues related to the federal taxation and variations in land ownership.

Some recent issues have further impeded compliance with federal taxation for AI/AN producers. Two separate but related events occurred in the mid- to late-2000s which resulted in an increased use of Form 1099 (more specifically, Form 1099-G that is sent by a government agency such as the USDA to report program payments to the program recipients and to the IRS).

The tax gap is the difference in the amount actually paid in federal taxes and what should have been paid. In a three-year study by the National Research Program, 2001 tax returns were audited to discover the significance of the tax gap. Preliminary findings in 2005 estimated there was over $312 billion in unpaid taxes. Under-reporting of taxes owed accounted for more than 80% of the tax gap, primarily from the understating of income. Income is more likely to be reported when a third-party either withholds income for taxes or reports that income to the IRS. The study showed that less than 1.5% of wages and salaries are misreported; this group, notably, had third-party withholding (IR-2005-38).

In 2006, the U.S. Department of the Treasury released a report on strategies for reducing the tax gap. One was for the IRS to improve document matching and become better at detecting unreported income. The IRS has acted on this and continues to become more sophisticated at matching information from Form 1099s to specific lines on IRS forms. The report also concluded that “about 54% of net income from proprietors (including farms), rents, and royalties is misreported,” and then called for increased information reporting.

At the same time the research on the tax gap was being released, the U.S. House of Representatives re-instituted pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) in 2007 and the U.S. Senate adopted a similar rule for fiscal year 2008. PAYGO requires that any increases in mandatory spending must be offset or paid for by a tax increase or a cut in other mandatory spending areas. With PAYGO in place, Congress viewed a potential decrease in the tax gap as a source of additional tax revenue that could pay for other programs. While PAYGO was not enforced due to economic issues, it did provide an incentive for Congress to mandate that the IRS close the tax gap.

The IRS increased its ability to automatically match revenue reported on Form 1099-Gs from recipients of government program payments such as the EQIP to an individual’s tax return. The IRS automatically assesses additional taxes owed and notifies the taxpayer. However, no clear guidance was issued on how to correctly file a tax return that reported the income from the Form 1099-G received when the recipient was exempt from federal taxes. AI/AN producers who are exempt may have never filed a tax return. Even though they may not owe any taxes on the EQIP payment, the IRS cannot distinguish an exempt taxpayer and attempts to match the return to the 1099-G received. In the absence of a return, the IRS assesses interest and penalties.

Because USDA employees are not tax professionals, they cannot warn program recipients of the need to file a return reporting the amounts from Form 1099s even if they are exempt from federal taxes. As a result, some AI/AN farmers who subsequently applied and were approved for an additional USDA program did not receive the funds from that program. These funds were essentially garnished and applied towards the taxes that had been assessed by the IRS for the previous government program payment received.

The situation has been several hundred years in the making and will not be easy to remedy. This article presents only a brief outline of some of the problems; the situation is complex and involves the interaction of many government agencies and other groups. As such, possible solutions will need to be carefully considered. In many cases, there is no legal remedy as laws have not been developed to fully embrace the legal framework of co-sovereignty within the borders of the United States. Below are a few potential solutions.

In order to unravel the underlying issues, clear IRS rulings and guidance are needed on how to achieve tax compliance when some or all of an AI/AN producer’s land is exempt from taxes. For this to happen, Congress would have to pass legislation making these unique exemptions part of the Internal Revenue Code.

Until such time, education will be required to keep the affected people aware of how to work around the problems already in existence and those that continue to arise. To accomplish this goal, resources will need to increase for both the number of educators within Indian Country and the educational materials required to provide information to the AI/AN producers on how to best address their individual tax issues.

Given that the congressional and treaty issues will take an enormous amount of effort and time to be implemented, possible partial, less-complex solutions need to be explored which can minimize the negative impacts of the issues. Getting around the fear by some AI/AN agricultural producers to actually file a tax return when they have never done so is key. The development of a program or law allowing for new filers without fear of past audits could encourage increased participation in filings.

All AI/AN recipients of agriculture program payments should receive information indicating they need to file a tax return. Including a listing of resources available to assist them with their reporting could mitigate reporting errors. This approach can be accomplished within the USDA, rather than through any additional laws.

Finally, the ability of the AI/AN producer to verify his or her farm or ranch income and expenses through a third-party certification in order to qualify for many of the USDA programs may increase participation and minimize the need for additional laws or changes in the existing laws.

The intent of this discussion is to begin the dialogue and introduce some of the key issues as well as provide possible short-run, partial solutions. This article is not meant to advocate for any particular solution or determine which problems are the most troubling. There are groups working within Indian Country—such as the Intertribal Agriculture Council, the Federally Recognized Tribal Extension Program, 1994 tribal colleges, the Intertribal Tax Alliance, and the Indian Land Tenure Foundation—that can advocate for AI/AN producers on these issues.

There are additional issues with land ownership in Indian Country such as fragmentation, property and other types of taxes, and so on. These are beyond the scope of this paper, but may be part of conversations as solutions are sought. There is not an easy fix, but there are options available.

Atkinson, K.J., and Nilles, K.M. (2008). Tribal business structure handbook. The Office of the Assistant Secretary-Indian Affairs, U.S. Department of Interior.

General Allotment Act (or Dawes Act, or Dawes Severalty Act of 1887), February 8, 1887 (24 Stat 388, Ch. 119, 25 USCA 331), 49th Cong. Sess II, Chp. 119, pp. 388–391.

Goetting, M. and Ruppel, K. (2009). Partitioning an allotment. Fact Sheet #11. Available online: http://www.montana.edu/indianland/factsheets/factsheet11.pdf

Hiller, J.G. (2005). Is 10% good enough? Cooperative Extension work in Indian Country. Journal of Extension 43(6).

Housing Assistance Council. (1999). Cost based appraisals on Native American trust lands: a longitudinal analysis. Available online: http://www.ruralhome.org/storage/documents/nativeamericanappraisals.pdf.

Indian Land Tenure Foundation. (2012a). Checkerboarding. Available online: http://www.iltf.org/land-issues/checkerboarding.

Indian Land Tenure Foundation. (2012b). Fractionated ownership. Available online http://www.iltf.org/land-issues/fractionated-ownership.

Indian Land Tenure Foundation. (2012c). Sovereignty & jurisdiction. Available online: http://www.iltf.org/land-issues/sovereignty-and-jurisdiction.

Indian Tribal Governments. 2013. Available online: http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-tege/itg_specialists.pdf.

Intertribal Ag Council & USDA Risk Management Agency. (2010). 2010 Tax Guide for Native American Farmers and Ranchers. Available online: http://www.indianaglink.com/IAC-TaxGuide.pdf

IR-2005-38. New IRS study provides preliminary tax gap estimate Available online: http://www.irs.gov/uac/New-IRS-Study-Provides-Preliminary-Tax-Gap-Estimate.

Keepseagle v. Vilsack Settlement. (2011). Available online: http://www.indianfarmclass.com/.

Nash, D., and Burke, C. (2006). Passing title to tribal land and federal probate of American estates. Report December 2006, p. 3.

National Archives Library Information Center. (2013). Indians/Native Americans. Available online: http://www.archives.gov/research/alic/reference/native-americans.html.

Nickerson, C., and Hand, M. (2009). Participation in conservation programs by targeted farmers: beginning, limited-resource, and socially disadvantaged operators’ enrolment trends. USDA Economic Information Bulletin 62. Available online: http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/150252/eib62.pdf.

Nilles, K.M. (2012). Taxation and reporting of ranching income in Indian Country. Holland and Knight, LLP. Presented at the 2012 National Intertribal Tax Alliance Conference, Tulsa, Ok, May 26, 2012.

Tribal Energy and Environmental Information Clearinghouse. (2013). Tribal and Indian land. Available online: http://teeic.anl.gov/triballand/index.cfm.

University of Oklahoma Law Center. (2013). Tribal constitutions, treaties and codes across the United States. Available online: http://thorpe.ou.edu/const.html.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2012). About USDA – A quick reference guide. Available online: http://www.usda.gov/documents/about-usda-quick-reference-guide.pdf

U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Reclamation. (2007). Chapter 5: Indian trust assets and trust lands. New Melones Resource Management Plan Environmental Impact Statement Resource Inventory Report.

U.S. Department of Treasury Office of Tax Policy. (2006). A comprehensive strategy for reducing the tax gap. Available online: http://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Documents/otptaxgapstrategy%20final.pdf.

Western Center for Risk Management. (2012). Considerations for grant proposals involving Native American farm & ranch families.

Zelio, J. (2005). Piecing together the state-tribal tax puzzle. The National Conference of State Legislatures. Available by request at http://www.ncsl.org/issues-research/tribal/state-tribal-relations-publications.aspx#PS