On December 17, 2014, U.S. President Barack Obama and Cuban President Raul Castro simultaneously announced that discussions to resume diplomatic relations would commence. This was a watershed event, as it represented a new level of interaction between the governments of the neighboring countries that had been limited for more than 50 years. In the summer of 2015, the negotiations were successfully concluded, and the “Interest Sections”—offices operated by the United States in Havana and by Cuba in Washington, D.C., under the auspices of the Swiss Embassies in both countries—became formal Embassies, launching a new era of relations.

While this is a striking departure from U.S. policy on the diplomatic front, it did not materially change U.S.-Cuba trade relations because the U.S. embargo remains in place. The 1996 Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act—the Libertad Act, or Helms-Burton legislation—codified the embargo into law, thus a lifting of the embargo now requires House, Senate, and Presidential approval (Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act, 1996). The prospects for such a development in the present political climate would appear uncertain in the near term.

Nevertheless, important developments have been taking place on U.S.-Cuban trade since 2000, when the U.S. Congress passed and then President Bill Clinton signed the Trade Sanctions Reform and Export Enhancement Act (TSRA, 2000) which allowed U.S. firms to sell food and agricultural products and medicine to Cuba for the first time in nearly 40 years. Under the TSRA, U.S. farmers, ranchers, and food processors have been major players in Cuba’s food import market, shipping over $5 billion worth of food and agricultural products to Cuba; in fact, from 2003 through 2010, the United States was Cuba’s most important supplier of imported food products. However, after peaking at nearly $700 million in 2008, the value of U.S. food and agricultural exports to Cuba has been declining while Cuban purchases of imported food products from other countries have been generally increasing for the last seven years.

But how will the new diplomatic dynamic affect future U.S. food and agricultural product sales to Cuba? Understanding the current situation in Cuba’s agricultural sector—including Cuba’s food import patterns and the shifting historical role of the United States as a supplier, as well as relevant third-country policy developments—offers insights on likely U.S.-Cuba trade relations.

Cuba is a large island with over 15.5 million acres of arable land (Anuario Estadistico de Cuba, 2015). In addition, Cuba has a warm tropical climate with no freeze risk, good soils, generally good rainfall patterns—although drought is a periodic problem, including for the last several years—and a strong, historical agricultural tradition. Thus Cuba would appear to have very significant agricultural production potential.

However, in 2007 Cuban Vice-Minister of Economy and Planning Magalys Calvo made a surprising public statement, acknowledging that Cuba imported “84% of the basic foodstuffs distributed to the Cuban people” (Granma, 2007). While subsequent reports have suggested that the actual percentage is somewhat lower, Cuba remains heavily reliant on imported food products. For the past two years, Cuba’s has spent nearly $2 billion annually on food imports, which represents a significant burden on the Cuban economy.

While Cuba had been producing and exporting sugar since earliest colonial times, it wasn’t until the 1830s that sugar began to dominate the island economy (Jenks, 1928). In the late 1950s, Cuba was an important supplier of sugar to the U.S. market. Between 1956 and 1958, Cuba supplied an average of over 2.8 million tons of sugar to the United States per year, which is very nearly as much as the average total U.S. imports of sugar from all foreign suppliers for the three-year period of 2012 to 2014 (Zahniser et al., 2015).

Following Fidel Castro’s rise to power in 1959, in the following year, the United States placed an embargo on trade with Cuba and Cuba’s access to the U.S. sugar market was lost, along with other special trading arrangements. In response, Castro began to speak about diversifying Cuba’s agricultural economy away from the sugar monoculture. However, the Soviet Union quickly stepped in and offered to pay Cuba high, preferential prices for its sugar.

By the late 1980s, Cuba was producing nearly 8.5 million tons of sugar per year, which made it the third largest sugar producer in the world after Brazil and India, and the largest sugar exporter in the world. With the Soviets paying Cuba prices that were sometimes as much as 11 times higher than the world sugar price (Bain, 2005), Cuba’s sugar industry was driving the entire Cuban economy, generating approximately 85% of Cuba’s total export earnings. These sugar purchases formed the basis for Soviet subsidies that totaled over $6 billion per year by the late 1980s (Sweig, 2016). Cuba used the proceeds from its sugar exports to purchase needed food imports.

This sweet deal ended for Cuba with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. Without a preferential market for its sugar exports, Cuba had to begin selling its sugar on the world market at world market prices. The collapse in the value of its sugar exports severely restricted Cuba’s ability to import inputs of critical importance to the functioning of Cuba’s agricultural sector and, indeed, all sectors of commerce, and industry, and these developments threw the entire Cuban economy into a tailspin.

Following the loss of the Soviet-subsidized purchases, Cuba was not competitive selling sugar at world market prices. Thus the Cuban sugar industry began a slow and inexorable decline that bottomed out with the 2010-2011 sugar harvest totaling only 1.1 million tons, less than 15% of its volumes from the late 1980s and the lowest production volume in more than a century.

As the economic impact of the loss of Soviet subsidies set in, Cuba was without access to external or internal sources of capital to invest in refocusing its agricultural production. Furthermore, production of food crops in Cuba declined due to a lack of inputs, leading to Cuba being even more heavily dependent on imported food products to satisfy domestic demand.

Shortly after the loss of Soviet subsidies, Venezuela began to provide financial assistance to Cuba, and this support increased significantly following the election of Hugo Chávez as President of Venezuela in 1999. Venezuela’s support takes the form of crude oil and related sales to Cuba; in exchange for these oil shipments, Cuba sends doctors, nurses, and teachers to work in Venezuela at terms of trade very favorable to Cuba. With the Venezuelan economy experiencing its recent downturn driven largely by low oil prices, Venezuelan oil shipments to Cuba have been declining, with ominous consequences for Cuba’s economic situation.

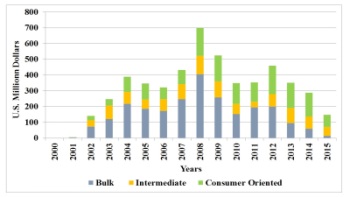

Source: USDA-FAS GATS

The U.S. government’s TSRA legislation of 2000 was passed as a humanitarian gesture, albeit with two key constraints. Sales had to be on a cash basis and since U.S. and Cuban banks could not conduct business directly with one another, all letters of credit had to be processed through third-country banks thus adding to the transaction costs. Arrangements for direct banking transactions are presently being negotiated. Further, only one-way trade was allowed—U.S. firms could ship to Cuba, but Cuba could not ship any products to the United States.

In November of 2001, Hurricane Michelle imposed significant damage to agriculture and infrastructure across a large portion of Cuba. Despite previous protest of the TSRA terms, the Cuban government indicated that it now wanted to purchase food products from the United States, reportedly to replace crops in the field and stored food products that were destroyed or damaged by the storm.

After not having shipped any products to Cuba in almost 40 years, U.S. agribusiness firms and shipping companies responded rapidly to this opportunity, delivering over $4.5 million of food and agricultural products to Cuba in the last six weeks of 2001 (Figure 1).

Clearly Cuba was doing more than replacing lost crops and food stocks after the storm as Cuba’s purchases of food and agricultural products from the United States grew to reach a peak of nearly $700 million in 2008.

After growing steadily from 2001 through 2004, U.S. agricultural sales to Cuba declined in 2005 and 2006, largely as a result of an announcement by the U.S. government in late 2004 that it was going to reassess the specifics of the “cash sale” terms under which U.S. firms had been selling to Cuba. In 2004, the United States supplied an estimated one-third of Cuba’s total food supply. This heavy reliance on a supplier whose policies were in flux was perceived by Cuban government officials to be risky, thus driving the decision to decrease purchases from the United States in 2005 and again in 2006. But when the new U.S. cash sale terms were announced in late 2006, the Cuban government found them to be acceptable and increased its purchases from the United States in 2007 to $440 million—a level even higher than that of 2004.

U.S. food and agricultural exports to Cuba peaked in 2008 at nearly $700 million. However, 2008 was a year of particularly high global commodity prices. An analysis of the trade data indicates that only about 20% of the increase in value between 2007 and 2008 was driven by increases in the volume of purchases, with the balance due to higher commodity prices (USDA-FAS GATS and authors’ calculations).

In 2009, Cuba’s purchases from the United States began to decline again as other countries offered Cuba larger lines of credit for its food purchases, in some cases with extended payment terms of as long as 12 to even 24 months. This declining trend in Cuba’s food and agricultural purchases from the United States continued through 2015 when the value fell to $149 million.

The composition of Cuba’s purchases from the United States has shifted significantly over time. What is evident in Figure 1 is Cuba’s shift away from purchasing bulk grains from the United States, with shipments collapsing from over $400 million in 2008 to only $15 million in 2015.

Since 2009, when U.S. bulk commodity sales to Cuba began to decline, the largest single commodity that Cuba has been purchasing from the United States has been poultry meat—a consumer oriented product. Cuba generally purchases lower value leg quarters, and they are able to obtain very favorable prices from U.S. suppliers. Another advantage for Cuba in purchasing these products from the United States is the quick transportation time because of the geographic proximity, which is a benefit for a highly perishable commodity like poultry meat. Poultry meat exports have increased their share of total U.S. exports to Cuba from 20% in 2008 to over 50% in each of the past two years.

Cuba’s purchases of food and agricultural products from the United States through the first quarter of 2016 declined 30% from 2015 levels, suggesting continued decreases for 2016. However, since April, Cuba’s purchases from the United States have increased to the point where, through the first eight months of 2016, the value of Cuba’s purchases from U.S. firms increased by 11% over the same period in 2015 (USDA-FAS GATS, 2016). The majority of the growth in U.S. sales to Cuba experienced since April of 2016 is in exports of bulk commodities such as corn and soybeans.

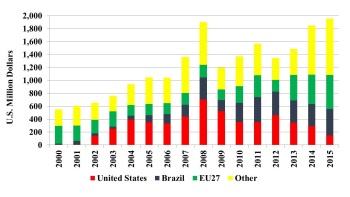

Source: GTIS (various years).

Figure 2 depicts Cuba’s overall food and agricultural imports, broken down by country or region. The red bar at the bottom of the stacked bar graph is U.S. food and agricultural sales to Cuba. What is particularly noteworthy is that the decline in the value of U.S. food exports to Cuba since 2008 has occurred at a time when Cuba’s food purchases from other countries have been increasing to the point where Cuba purchased almost $2 billion worth of food and agricultural products in each of the past two years. This shift has resulted in the U.S. share of Cuban food imports decreasing from over 40% in 2004 to less than 8% in 2015 (GTIS).

Between 2003 and 2013, the United States was Cuba’s most important supplier of imported food products in every year but 2011, when Brazil edged narrowly ahead of the United States. Since 2013, Brazil has been Cuba’s most important supplier of imported foods.

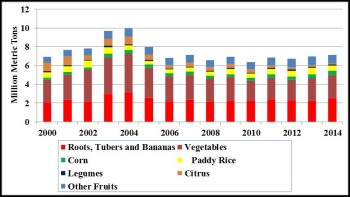

Source: Annario Estadistico de Cuba (various years)

Despite having very significant agricultural production potential, Cuba’s agricultural sector remains stagnant (Figure 3). The only agricultural commodity that has managed to achieve any notable increase in output over the past five years is its sugar industry, but the growth in Cuba’s production of sugar has been driven by Brazilian investment (Israel, 2012). Thus foreign investment would appear to be crucial to boosting Cuba agricultural output.

In fact, in 2014, Cuba’s Vice-President and economy and planning czar Marino Murillo and Minister for Foreign Trade and Investment Rodrigo Malmierca both publicly stated that “Cuba needs from $2 billion to $2.5 billion a year in direct foreign investment to advance its socialist socioeconomic model” and to meet GDP growth goals (Associated Press, 2014; Trotta, 2014). Thus foreign investment is critical to the entire Cuban economy, but foreign investment flows into Cuba are well short of meeting this goal.

With licensing and approval from the U.S. government, it is now possible for U.S. firms to invest in Cuba, and earlier this year the Starwood Hotel chain>—parent corporation of the Sheraton Hotel brand, and now part of Marriott—received authorization to manage the state owned Gran Caribe Inglaterra Hotel and the military owned Gaviota 5th Avenue Hotel in Havana under what was reported to be a multimillion dollar arrangement (Fortune, 2016; Starwood, 2016). Such projects are typically joint ventures in which the Cuban government is the majority partner, and not all investors are comfortable with this sort of arrangement. Nevertheless, firms from other countries have been investing in Cuba for over 20 years in a wide range of industries including hotels, nickel mining and agriculture with varying levels of success. But lack of access to the U.S. market for Cuban goods because of the embargo makes investments in agricultural or manufacturing operations less attractive due to the lack of “effective demand” in Cuba as measured by the ability to pay, where average state salaries in Cuba are only $25 to $30 per month. While Cuba’s foreign investment laws are gradually evolving, they have not yet reached what most would consider to be international standards (Whitefield, 2015).

In its 2011 Communist Party Congress, the Cuban government adopted a series of unprecedented—since the 1959 Revolution—market-oriented policy adjustments for the agricultural sector and, in fact, for most sectors of the Cuban economy (Lineamientos, 2011). In the ensuring years, relatively few of these policy changes have been implemented effectively. In Cuba’s subsequent Party Congress in April of 2016, much time was spent discussing methods to more effectively implement the changes mandated in 2011 (Whitefield, 2016). Given all of these factors, the prospects for any substantial increase in production or productivity for Cuba’s agricultural sector do not appear promising in the near term.

Complicating the food situation further, the explosion of tourist travel to Cuba—including American citizens on “People-to-People” trips following the recent relaxation of some restrictions on U.S. travel to Cuba—has resulted in a rapid increase in the demand for food in tourist hotels and the expanding number of Cuba’s private restaurants, known as paladares. This increase in demand has brought about significant food price increases, exacerbating food access challenges for Cuban consumers on their limited incomes. In fall of 2015, the Cuban government acknowledged this problem and implemented policies to make food more readily available to the Cuban people at prices more in line with their limited purchasing power (Café Fuerte, 2016).

Between Cuba’s stagnant agricultural output and the increased demand for food due to the rise in tourists visiting the island, Cuba is expected to remain heavily reliant on imported food products in the short- to medium-term. The mix of imported commodities will continue to cover a wide range of products, from rice and other grains to feed the Cuban people, to high value products to meet the demands of the tourist trade.

Because of cash flow and balance of trade challenges facing the Cuban government, the lure of extended credit terms received from other countries appears to be driving Cuba’s purchasing decisions. This being the case, the cash payment regulations of the TSRA are likely to continue to be a major hindrance to U.S. suppliers regaining a significant portion of their lost market share in Cuba.

One of the limitations faced by Cuban farmers is the shortage of fertilizers and other agrichemicals. The Cuban government prides itself on its commitment to organic agricultural practices and, indeed, Cuba may be the largest experiment in organic, or at least low input agriculture in the world. That said, an increase in the availability of agrichemical inputs—organic or traditional—could make an important contribution to improving Cuba’s agricultural yields which for some crops are only 25 to 30% of typical U.S. yields (Anuario Estadistico). Cuban can legally import fertilizers from the United States under the TSRA, although not pesticides, but has chosen to import only very small volumes. Similarly, Cuba has not imported much in the way of agrichemical inputs from any foreign suppliers since the loss of its preferential trading relationship with the former Soviet Union. Cuba has reportedly obtained organic certification for exports of honey, coffee, cacao, and some citrus products to Europe.

Finally, another challenge that Cuba faces is their dual currency system. The Cuban Convertible Peso—CUC— is tied to the U.S. dollar at one-to-one, although there is a tax of 10% to 13% charged for exchanging dollars for CUCs. Meanwhile, the Cuban Peso—CUP, or moneda nacional— exchanges at a rate of 24 or 25 CUP to 1 CUC. In 2013 the Cuban government announced its plan to eliminate the dual currency system, although the process has not been launched and it is unclear when it will be implemented. CUCs cannot be exchanged outside of Cuba.

In recent years, Brazil has become increasingly involved with Cuba. This involvement goes well beyond the aforementioned foreign investment in Cuba’s sugar industry and food sales, and includes a $680 million investment in infrastructure at Cuba’s new commercial port at Mariel. However, the current economic and political situation in Brazil suggests that further government support for and economic assistance to Cuba may not be forthcoming, at least in the short run.

Because of their geographic proximity, the United States and Cuba had historically been important trading partners until the Cuban Revolution of 1959. In fact, in 1942 USDA economist P.G. Minneman (1942) observed that “with no other country does the United States have as close economic relations as with Cuba.”

Deere (2015) presents a thorough analysis of the extensive U.S.-Cuban ties and relationships in agricultural investment and trade from 1902 to 1962. Under a scenario of resumed trade and commercial relations—that is, a lifting of the embargo—it is conceivable and perhaps even likely that the United States could reacquire a particularly important role as an economic and trading partner for Cuba. And following a lifting of the U.S. embargo, Cuba could become an important competitor in the U.S. winter vegetable and fruit markets, potentially altering the competitive structure of the winter fresh produce industry in ways not unlike the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) did over two decades ago. In the meantime, Cuba is likely to remain heavily reliant on imported food products as it struggles to revive its flagging agricultural sector.

The role that the United States will play as a supplier of food to Cuba remains unclear. Given recent trends, the prospects for U.S. suppliers recovering a substantial share of Cuba’s food import market do not look promising because of the specific provisions of the TSRA prohibiting credit sales. Legislative initiatives at various stages of development could change this dynamic. But despite the resumption of diplomatic relations and regardless of legislative initiatives which may be passed, given the hostile approach of the United States toward Cuba for the past half century, one should keep in mind that suspicion and caution still characterize the Cuban government’s view of the aims and intent of the U.S. government in its dealings.

Anuario Estadistico de Cuba. 2015. Oficina Nacional de Estadística e Información. República de Cuba.

Associated Press. 2014. “Cuba Moves to Attract More Foreign Investment. New York Times. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/30/world/americas/cuba-moves-to-attract-more-foreign-investment.html?_r=0.

Bain, M.J. 2005. “Cuba-Soviet Relations in the Gorbachev Era.” Journal of Latin American Studies 37(4):784.

Café Fuerte. 2016. “Cuba Cuts Prices by 20% on Food Products. Available online: http://www.havanatimes.org/?p=118290.

Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity (Libertad) Act of 1996 (Helms–Burton Act). 1996. Pub. L. 104–114, 110 Stat. 785, 22 U.S.C. §§ 6021–6091.

Deere, C.D. 2015. “The ‘Special Relationship’ and the Challenge of Diversifying a Sugar Economy: Cuban Exports of Fruits and Vegetables to the United States, 1902 to 1962.” Working Paper #1, Cuba-US Agricultural Research Working Paper Series. University of Florida. Available online: http://www.latam.ufl.edu/media/latamufledu/website-pdfs/WP1_Deere_-Special-Relationship_-REV-March-2016_WO.pdf

Fortune. 2016. “This New Luxury Hotel in Havana Is Making U.S.-Cuba History.” Reuters. Available online: http://fortune.com/2016/06/28/sheraton-hotel-havana-cuba/.

Granma. 2007. “Cuba to Increase Food Production.” Granma, Official Newspaper of the Communist Party of Cuba. Available online: http://www.granma.cubaweb.cu/2007/feb26economiacuba.htm.

Global Trade Information Services (GTIS). “Annual Module.” N.D. Available online: https://www.gtis.com/annual/.

Israel, E. 2012. “Brazil to Breathe Life into Faded Cuban Sugar Sector.” Reuters.com. Available online: http://af.reuters.com/article/energyOilNews/idAFL2E8CUA7620120130.

Jenks, L.H. 1928. Our Cuban Colony—A Study in Sugar. New York, NY: Vanguard Press.

Lineamientos de la Política Económica y Social del Partido y la Revolución. 2011. “VI Congreso del Partido Comunista de Cuba.” Available online: http://www.juventudrebelde.cu/file/pdf/suplementos/lineamientos-politica-partido-cuba.pdf.

English Translation:

Guidelines for Economic and Social Policy of the Party and the Revolution. 2011. “Sixth Congress of the Communist Party of Cuba.” Official Cuban translation in English Available online: http://www.cuba.cu/gobierno/documentos/2011/ing/l160711i.html.

Minneman, P.G. 1942. “The Agriculture of Cuba.” U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Washington, D.C.

Starwood Hotels website. Available online: http://www.starwoodhotels.com/fourpoints/property/overview/index.html?propertyID=4531&language=en_US.

Sweig, J.E. 2016 (3rd ed). Cuba: What Everyone Needs to Know (3rd edition). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Trade Sanctions Reform and Export Enhancement Act (TSRA). 2000. Available online: http://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title22/chapter79&edition=prelim.

Trotta, D. 2014. “Cuba Set to Approve Law Aimed at Attracting Foreign Investment.” Reuters.com. Available online: http://www.reuters.com/article/cuba-investment-idUSL1N0MQ0B720140329.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service's Global Agricultural Trade System (USDA-FAS GATS). USDA/FAS Global Agricultural Trade System (GATS) database. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service. Available online: http://apps.fas.usda.gov/GATS/default.aspx.

Whitefield, M. 2016. “Cuba’s Communist Party Congress Wants Change, but Also More of the Same.” Miami Herald. Available online: http://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/cuba/article72522672.html.

Whitefield, M. 2015. “Cuba’s Open for Some American Business – So Here Come the Lawyers.” Miami Herald. Available online: http://www.miamiherald.com/news/business/international-business/article22255623.html.

Zahniser, S., B. Cooke, J. Cessna, N. Childs, D. Harvey, M. Haley, M. McConnell, and C. Arnade. 2015. “U.S.-Cuba Agricultural Trade: Present and Possible Future.” Washington, D.C. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Publication Number AES-87. Available online: http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/1856299/aes87.pdf.