Organizations broadly described by F. Bailey Norwood (2015) as being representative of the “Food Democracy” encourage more involvement in the food system and seek to empower and make consumers more aware of the effects associated with various food choices. Historically, consumers, by and large, have not had experience in contemplating the impact of food choice on the environment and other consumers, both now and in the future. Conversations about where and how food is produced are becoming more mainstream and the Food Democracy is partly to thank for that.

It would be a mistake to aggregate all food activist organizations together, even the organizations mentioned by Norwood, and collectively define them as the Food Democracy. Some organizations mentioned as representatives of the Food Democracy seek to increase access to nutritious food and inform consumers about the ecological implications of food systems. The goal of the Toronto Food Policy Council, for example, is to ensure access to healthy affordable food and support a healthier and more sustainable food system. Mother Earth News is a magazine that provides information about organic farming and green living. These organizations do not exist to criticize large corporations, rather they exist to promote choices and behavior that may indirectly decrease the revenues of some large corporations. Other organizations and individuals mentioned as members of the Food Democracy behave more like special interest groups that vilify certain corporations in the food system. A look at the social media campaign by Food Democracy Now! leaves little to the imagination about which corporation is the enemy.

A perspective put forth in understanding the mind of a food activist was that, “behind ‘free markets’, there is always corruption.” However, there are ample examples of how the “free-market” is working for the Food Democracy. For example, organic sales were an estimated $35 billion in 2014, which is an increase of more than $20 billion in less than 10 years (USDA-ERS, 2014b). Organic producers appear to be geared to meet evolving consumer demand, as there has been a boon to new entrants — who many times get snatched up by the big guys once they are established—for example, Honest Tea and Coca Cola. If the Food Democracy has shifted away from organic to local because of large corporations buying up small organic brands, not to worry—the number of farmers’ markets has more than doubled over the past 10 years (USDA-ERS, 2014c). There are currently more than 8,000 farmers markets.

Almost all, 93%, of organic sales are currently taking place through retailers and recently, Wal-Mart—the world’s largest retailer—has made a commitment to stock more organic options (USDA-ERS, 2014b; Martin, 2014). Moreover, Wal-Mart is working to close the price gap between organic and conventional offerings. However, some food activists, like Wenonah Hauter (2012), have issues with the logistical system of Wal-Mart and the retailer power that it can create. Ironically, it is the logistic efficiency of Wal-Mart that will bring organic foods to the masses while making it more affordable. The increase in organic offerings at Wal-Mart is not evidence that the retailer wants to adopt the Food Democracy’s set of values, but rather the consumer really does have the power and the market can work.

Another example of the market working for the Food Democracy is the labeling of food with genetically modified organisms (GMO). The Non-GMO Project was created in 2005 with the goal of creating a reliable way of providing non-GMO foods. Straus Family Creamery was the first company to be verified by the Non-GMO Project. This occurred five years before California voted on Proposition 37 in 2012, which was the first ballot initiative for a mandatory label. Currently, there are more than 27,000 Non-GMO verified products.

We cannot say that the Food Democracy resentment for large corporations is uniform, and the resentment may be more associated with perceived, rather than real, market power. For illustration, let’s examine revenue for two corporations to which resentment is often directed— Monsanto and McDonalds—and two corporations that get a pass—Whole Foods and Chipotle. According to annual reports, in 2014 Monsanto’s revenue was $15.8 billion which was up from $14.9 in 2013, compared to Whole Foods’ revenue of $14.2 billion, which was up from $12.9 in 2013. McDonalds’ revenue was $4.8 billion in 2014, down from $5.6 in 2013, compared to Chipotle’s revenue of $4.1 billion, up from $3.2 in 2013. We realize that Monsanto is an input supplier and Whole Foods is a retailer, nevertheless, it would be difficult to define one of these companies as large and not the other.

Another perspective advanced was, “trade is never about trade.” This perspective suggested agreements are political and crafted to advance the interests of powerful corporations to the detriment of individuals. We weakly second the first conclusion and have doubts about the latter. Economists schooled in international trade theory understand that all nations can benefit, in aggregate, from free trade. But not every producer in a nation necessarily gains. The reality is that nation A does not engage in trade with a competing nation, B; rather, firms in nation A trade with firms in nation B. As a nation’s government engages in trade agreements with another nation(s), such agreements are inseparably linked to the political considerations. With the axiom “…all politics is local…,” notably attributed to former Speaker of the House of Representatives Tip O’Neil, we have a proliferation of bilateral and multilateral free trade agreements that address food and other products and services. When it comes to the food industry and trade, global food firms own facilities and distribution activities globally. And, according to the leading database on 180 million firms worldwide (van Dijk, 2016) these firms are few —approximately 1/5th of 1% of the 106,294 U.S. food manufacturing firms.

Consequently, we concur that trade policies and agreements are likely to be for the benefit of powerful firms, but this does not preclude these same agreements being able to offer the opportunity for the less powerful agents to participate and benefit as well. Further, there are many food choices available to consumers who can certainly apply the lens of other considerations—such as favoring local producers—in making decisions.

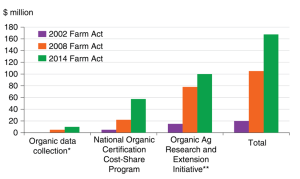

*Include $5 Million in 2014 for National Organic

Program database and technology update

**Does not include intramural organic research

funds in USDA, Agricultural Research Service

Source: Office of Budget and Policy Analysis

budget summary data (2002), Congressional

Budget Office (2008), and 2014 Farm Act.

A perspective put forth in understanding the mind of a food activist was to, “replace bad politics with good politics.” However, governmental agencies are directing public funding to issues the Food Democracy favors, like increasing access to food. Projected outlays under the 2014 Farm Act, which authorizes nutritional and agricultural programs from 2014 through 2018, total approximately $489 billion (USDA-ERS, 2014d). Eighty percent of the $489 billion is devoted to nutrition, which includes the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) (USDA-ERS, 2014d). The number of SNAP participants has increased from less than 30 million participants in 2008 to more than 45 million participants in 2014 (USDA-ERS, 2014e).

In an attempt to increase the consumption of fruits and vegetables for people with low income and low access, the USDA provides free wireless equipment to farmers markets that accept SNAP benefits. It appears that this initiative is working because the number of SNAP-authorized farmers markets or roadside stands has increased from 753 in 2008 to more than 6,400 presently (USDA-FNS, 2015). Additionally, the USDA is providing $3.3 million in competitive funding to assist farmers markets in better serving SNAP participants and $31.5 million in funding to support programs that encourage SNAP participants to purchase more fruits and vegetables (USDA-FNS, 2015). Furthermore, the 2014 Farm Bill increased mandatory spending on organic agriculture to over $160 million (Figure 1) (USDA-ERS, 2014f).

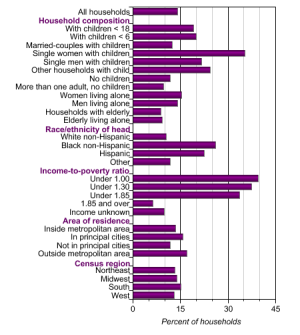

Source: Calculated by ERS using data from

the December 2014 Current Populations

Survey Food Security Supplement

The 17 Sustainable Development Goals, adopted at a United Nations (UN) summit in 2015, was put into effect in January of 2016. Goal 2 is to end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture (UN, 2015). A target of this goal is, “By 2030, ensure sustainable food production systems and implement resilient agricultural practices that increase productivity and production, that help maintain ecosystems, that strengthen capacity for adaptation to climate change, extreme weather, drought, flooding and other disasters and that progressively improve land and soil quality.” Sustainability is receiving more attention because of the burdens impending population growth and climate change will place on our finite resources. The concern is that these burdens will increase food insecurity.

Currently, about 15% of U.S. households are food insecure (Figure 2) (USDA-ERS, 2014a). Food insecurity is higher in much of the world; greater than 35% of some populations are food insecure in some developing areas. In the United States, food insecurity is more severe for households with children and a single parent. Thirty-five percent of single mother households and more than twenty percent of single father households are food insecure.

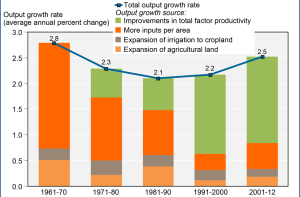

When Food Democracy discusses sustainability and agriculture, the tradeoff between sustainability and food prices is rarely raised. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development suggested small-scale organic farming as the answer for “feeding the world” (UNCTAD, 2013). In theory, it is possible to increase sustainability while decreasing food prices. One way is by adopting technologies that increase output while maintaining or decreasing the amount of resources used for production. As shown in Figure 3, improvements in total factor productivity are responsible for most of the growth in global agricultural output (USDA-ERS, 2015). Another way is by moving production to an area that is more efficient at producing an output. However, discussions about increased sustainability in agriculture are often limited to advocating production methods that decrease resource use at the expense of decreased output. Decreased output will most always lead to an increase in price and, invariably, a tradeoff between sustainability and food prices.

Source: USDA-ERS, International Agricultural

Productivity data product, October 2015

There are many causes of food insecurity, access being one, but lack of income is surely the main driver. Members of the Food Democracy who advocate for production methods that decrease productivity are not saying, “We should increase food insecurity.” Nevertheless, it will be a consequence, albeit unintended, of a production method that increases prices because of decreased productivity.

Moving forward, society would benefit greatly by understanding the benefits and tradeoffs of different production methods. This is often difficult to do because some may have already taken a side on what the future of agriculture should look like. When taking a side, we open ourselves up to a host of problems like groupthink and conformation bias—we needn’t look too far for examples of this as we are in election season. Food security, both now and in the future, is too important to treat it like another controversial, politicized topic.

Hauter, W. 2012. “Foodopoly: The Battle over the Future of Food and Farming in America.” New York: The New Press.

Martin, A. 2014. “Wal-Mart Promises Organic Food for Everyone.” Bloomberg Business. Available online: http://www.bloomberg.com/bw/articles/2014-11-06/wal-mart-promises-organic-food-for-everyone

Norwood, F. B. 2015. “Understanding the Food Democracy Movement.” Choices. 30(4).

United Nations (UN). 2015. “Sustainable Development Goals: 17 Goals to Change our World.” Available online: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/hunger/

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). 2013. “Trade and Environment Review 2013: Wake up Before it is too Late.” Available online: http://unctad.org/en/pages/PublicationWebflyer.aspx?publicationid=666

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service (USDA-ERS). 2015. “Increased Productivity Now the Primary Source of Growth in World Agricultural Output.” Available online: http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/chart-gallery/detail.aspx?chartId=54192&ref=collection&embed=True&widgetId=37373

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service (USDA-ERS). 2014a. “Food Security in the U.S., Key Statistics & Graphics.” Available online: http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/chart-gallery/detail.aspx?chartId=54192&ref=collection&embed=True&widgetId=37373

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service (USDA-ERS). 2014b. “Organic Agriculture, Organic Market Overview.” Available online: http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/natural-resources-environment/organic-agriculture/organic-market-overview.aspx

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service (USDA-ERS). 2014c. “Number of U.S. Farmers’ Markets Continues to Rise.” Available online: http://ers.usda.gov/data-products/chart-gallery/detail.aspx?chartId=48561&ref=collection&embed=True&widgetId=37373

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service (USDA-ERS). 2014d. “Agricultural Act of 2014: Highlights and Implications, Overview.” Available online: http://www.ers.usda.gov/agricultural-act-of-2014-highlights-and-implications.aspx

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service (USDA-ERS). 2014e. “Agricultural Act of 2014: Highlights and Implications, Nutrition.” Available online: http://www.ers.usda.gov/agricultural-act-of-2014-highlights-and-implications/nutrition.aspx

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service (USDA-ERS). 2014f. “Agricultural Act of 2014: Highlights and Implications, Organic Agriculture.” Available online: http://www.ers.usda.gov/agricultural-act-of-2014-highlights-and-implications/organic-agriculture.aspx

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service (USDA-FNS). 2015. “SNAP Benefit Redemptions through Farmers and Farmers Markets Show Sharp Increase.” Available online: http://www.fns.usda.gov/pressrelease/2015/fns-0007-15

van Dijk, B. 2016. Orbis Data Base. Company Information and Business Intelligence. Available online: https://www.orbis.bvdinfo.com.

The views expressed in this article are not necessarily the views of the Agricultural and Applied Economics Association.