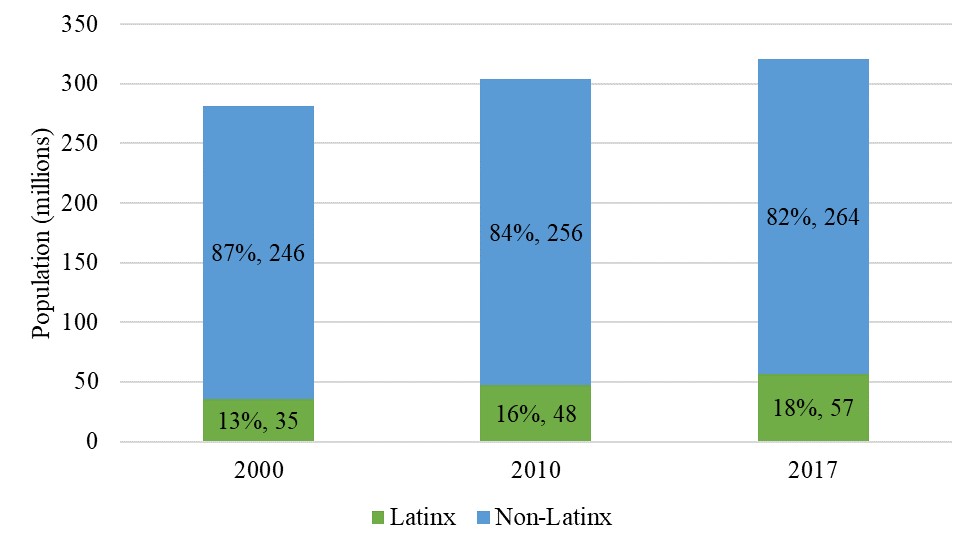

Notes: Here and throughout, many tables, figures, and

references rely on Hispanic population data from the US Census

Bureau, rather than Latinx population estimates. This reliance on

proxy data is due to the collection procedures of the US Census

Bureau. The authors acknowledge the difference between these

two overlapping populations, but note that the estimates are

similar; Hispanic is an ethnicity that refers to individuals with

Spanish-speaking ancestry and thus includes Spain and

excludes Brazil, while Latinx refers to individuals from Latin

American, including Brazil.

Source: American Community Survey (ACS) 5-year and

Decennial Census county-level data. The 2016 ACS estimated

350,000 Brazil-born and 83,000 Spanish-born people live in the

US. These totals are small compared with the foreign-born from

Latin America, which is over 23M (US Bureau of Census, 2019).

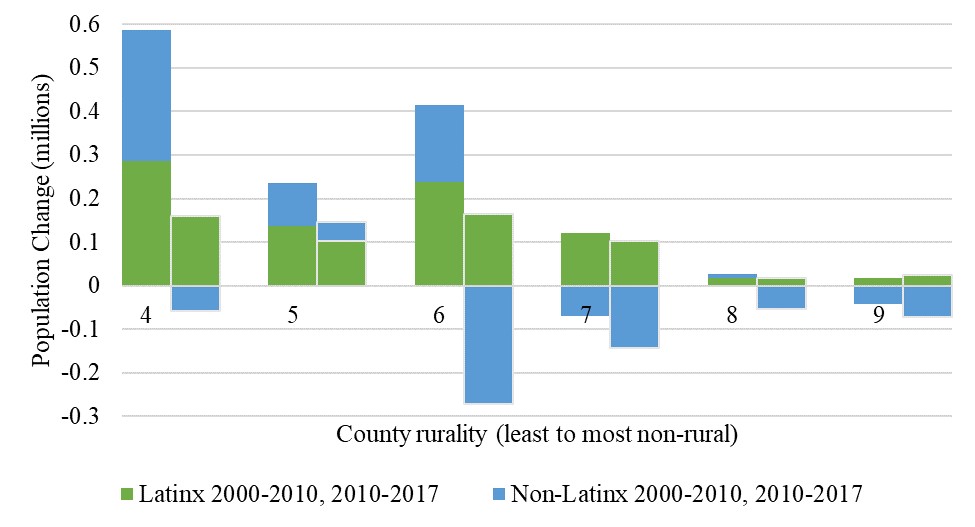

Notes: X-axis numbered by USDA Rural-Urban Continuum

Codes for non-metro county types.

Source: American Community Survey 5-year and Decennial

Census county-level estimates.

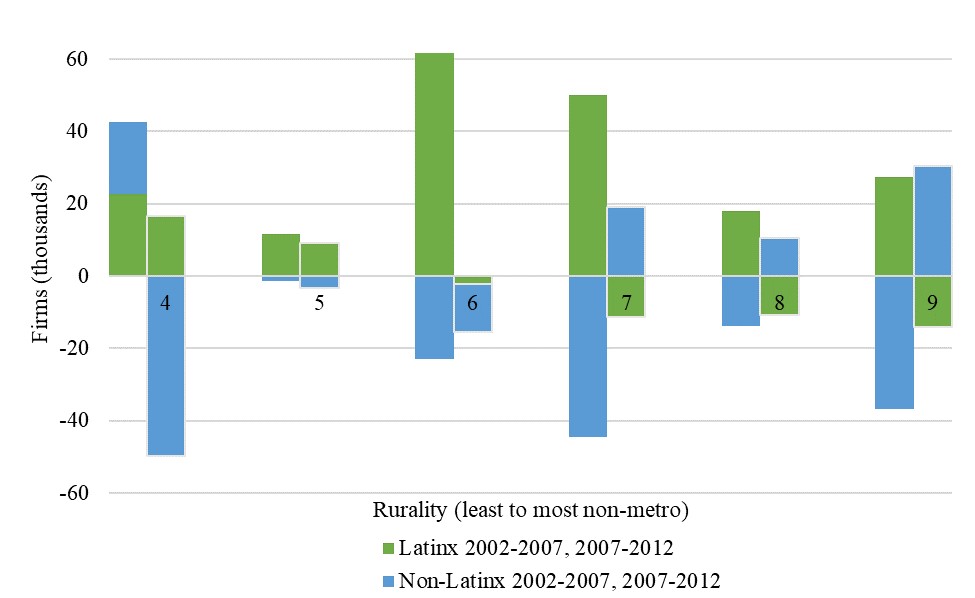

Notes: X-axis numbered by USDA Rural-Urban Continuum

Codes.

Source: Survey of Business Owners (SBO) county estimates.

Public data suppressions impact estimates in rural counties. The

SBO occurred in quinquennial years ending in 2 and 7. The SBO

was discontinued in 2012 in favor of a smaller annual survey.

The contributions of immigrant labor, especially Latinx labor,1 to the US agricultural sector are well known (See Horst and Marion [2019] for a review of the history and growth of Latinx farm workers). Latinx comprise 51% of hired agricultural workers; only 65% of agricultural workers are born in the US (Economic Research Service, 2018). Without immigrants, who are often temporary, labor-intensive cropping activities would likely be less feasible. The mechanization of agriculture facilitated a mass movement from farms to the cities that continues to the present era (Population Reference Bureau, 2003). Immigrants filled gaps in left-behind tasks that were difficult to mechanize, though they are increasingly also becoming farm operators as well. The ongoing rural out-migration produced other effects, as rural main street businesses closed or consolidated, and empty storefronts became commonplace in small-town America (Agranoff, 2020). A policy question is whether immigrants can fill some of the business voids in small towns as they have done with farm labor and farm ownership. Immigrants are characterized as being more entrepreneurial than stationary individuals (Carpenter and Loveridge, 2017). Policies could enhance this propensity.

The Latinx population has been increasing steadily across the rural-urban spectrum since 2000, reaching about 57 million or about 18% of the total population in 2017. Recent debates about stemming undocumented immigration mask upswings in workers arriving via both agricultural and non-agricultural visas (The Economist, 2020). Thus, Latinx population growth is likely to continue.

Although the total Latinx population makes up a smaller share of the population in rural areas, their rate of growth has been larger in rural areas. In addition, the non-Latinx population declined in many rural areas from 2000 to 2010, while the Latinx population increased (Gallardo and Bishop, 2020). These divergent trends increased in magnitude from 2010 to 2017 and spread to almost all non-metro county types (author calculations, see also Carpenter and Loveridge, 2017).

Put another way, without this growth in the Latinx population, the depopulation in rural and non-metro areas would likely have been larger and more widespread across the rural United States. Figure 2 shows this trend across a variety of non-metro county types. County Type 4 is the least rural, with a population of 20,000 or more and adjacent to a metro county. County Type 9 is the most rural with a population of less than 2,500 and no adjacent metro county.

One might expect Latinx businesses to follow similar trends across the rural-urban spectrum. This is not necessarily the case, due largely to two reasons. First, Latinx businesses are not a monolithic group with substantial gender, country-of-origin, and other aspects around which business survival and growth vary (Carpenter and Loveridge, 2019a; 2020). Second, the Great Recession differently impacted business survival and locational choice owners of various races and ethnicities (Jarmin, Krizan and Luque, 2015). Third, Latinx have a different relationship with self-employment and entrepreneurship than other ethnicities; for example, Latinx, not other ethnicities, drove much of the self-employment in US cities, at least prior to 2010 (Carpenter and Loveridge, 2017). Figure 3 shows that between 2002 and 2007, Latinx business growth is consistent with population growth, but between 2007 and 2012, these trends reverse for most rural counties.

Unfortunately, public data on Latinx businesses is often suppressed and only available in years ending in 2 and 7. This data’s survey source was discontinued in 2012 in favor of a smaller annual survey, which suffers from more significant data suppression issues in rural areas. As a result, the data presented here examines changes from 2002 to 2007 and then from 2007 to 2012.

Nonetheless, after reviewing some new research on Latinx entrepreneurs, we note some potential adaptations of current rural entrepreneurship policy. This data and research support the implications section below.

Researchers are increasingly interested in understanding factors associated with Latinx businesses’ success, but many of these have an urban focus, and the question of their applicability to rural Latinx entrepreneurs remained. Many of the existing works are case studies, and Canedo et al. (2014) call for more empirical studies. For example, case studies of Latinx entrepreneurs showed that urban environments are preferred and that interviewed firms were unaware of business services offered in Spanish (Munoz and Spain, 2015). A series of interviews in Springfield, Mass also found that Latinx owners were unaware of services tailored to small businesses (Munoz et al., 2011). A 2007 literature review concluded that Latinx business assistance needs may be bimodal due to the growing number of college-educated Latinx business owners and noted the need to better understand the linkages between owners and the communities in which they are embedded (Robles and Cordero-Guzman, 2007). A study of Latina professionals in Louisiana found that coethnic status was helpful within the community, but gender was more salient outside the community (Vallejo and Canizales, 2016).

While the urban-focused understanding of Latinx business is growing, the few rural studies focus on narrow geographies, so national rural policy prescriptions are not obvious. For example, a Latinx enclave study in South Texas (Pisani et al., 2017) found that owner gender, business language, and financial access play roles in whether the business is necessity or opportunity driven. In contrast, a study of northern Utah found that Latinx entrepreneurs in new destinations (e.g., northern Utah or the rural Midwest) rely less on ethnic networks than Latinx entrepreneurs in established destinations, but that this may be changing as these new communities grow (Smith and Mannon, 2020).

A clear limitation of these articles is their geographic specificity. By accessing federal administrative data on the entire United States, rural and urban, Carpenter and Loveridge (2018, 2019a, 2020) address concerns laid out by Canedo et al. (2014) and find a variety of factors impacting Latinx business growth and survival and are able to examine a sample covering the entire United States, rather than previous studies examining smaller geographies. The factors they examine include geographic region, specific owner demographics, and other business factors. The relative importance of these factors appears to be different for Latinx as opposed to other ethnicities. For example, manufacturing firms are less likely to be Latinx-owned than White-owned, but more likely to be Latinx-owned than Black-owned.

Additionally, Latinx owners are consistently less likely to be college-educated and more likely to have their business in rural areas than the other ethnic minorities, even after controlling for other factors. This research also has important public policy implications. For example, initiatives focused on the growth and survival of Latinx businesses should consider emphasizing outreach to underserved subgroups, which have worse rates of business survival, especially Latina or Puerto Rican business owners. Financing and rural site selection would improve odds for the growth and survival of Latinx businesses.

Although Latinx entrepreneurs may deserve special attention from local economic development practitioners, that Latinx individuals are not a monolithic group implies that for policymakers to understand and support Latinx businesses, they must understand the subtleties of their local community’s Latinx population, the industries, and their sources of financing. This will allow those same policymakers to increase the likelihood of Latinx business growth and success, and in turn, the ability to create spillover benefits for the local and regional economy, improving economic development in general. The benefits of these activities, some of which are intangible, need to be assessed against the costs.

Rural areas may not be taking advantage of the growth potential offered by Latinx owned businesses. Rural communities need individualized policies to improve outcomes for Latinx businesses and, in turn, local economic development. Given the growth in the Latinx population, policymakers must develop a complete understanding of business owner differences and take those differences into account in developing and implementing an effective economic development strategy.

For example, “economic gardening” has become a popular local economic development strategy. Economic gardening is regional economic development approach that focuses on fostering, growing, and supporting local entrepreneurs. It assumes that an economy can be grown from the inside, when local companies grow. Some economic development groups, including Extension, attempt to provide data and targeted services that improve the natural entrepreneurial process. Latinx entrepreneurship research indicates that business owners’ demographic data should be included in targeting services for economic gardening to succeed.

Some simple policy changes may also help. For example, the finding that education is not related to survival rates, but has a large effect on employment growth, is consistent with small- scale, primarily owner-labor business model enterprises. The challenge in working with these owners may be to find ways to reposition their accumulated informal business operations skills into trajectories with more hiring/employment growth potential. These shifts need not involve changing from one sector to another; for example, a local bakery might supply regional restaurants and grocery stores, before becoming a national supplier.

Implementing straightforward and low-cost policies to support Latinx businesses may help stabilize rural populations, incomes, and increase economic growth. Efforts to reach into local Latinx networks by hiring bilingual loan officers might help overcome the hesitancy to establish credit and the overreliance on personal savings for business expansion that research shows to impede growth (Carpenter and Loveridge, 2020). Assistance could also be given to establishing Spanish-speaking business groups. The US Hispanic Chamber of Commerce (USHCC) claims over 200 local chambers across the US, and offers resources for starting new chapters. That being said, the literature emphasizes the need for policymakers to avoid treating Latinx business owners as a monolithic group with a one-size-fits-all policy. Getting to know local Latinx entrepreneurs through informal conversations would be a good starting point.

Agranoff, R. “Government Rural Development Policy.” Handbook of State Government Administration (2020): 385.

Carpenter, C.W., and S. Loveridge. 2017. “Immigrants, Self-Employment, and Growth in American Cities.” Journal of Regional Analysis & Policy, 47(2):100–109. Available at: https://jrap.scholasticahq.com/article/7840-immigrants-self-employment-and-growth-in-american-cities.

Carpenter, C.W., and S. Loveridge. 2018. “Differences Between Latinx-Owned Businesses and White-, Black-, or Asian-Owned Businesses: Evidence from Census Microdata.” Economic Development Quarterly, 32(3):225-241. Available at: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0891242418785466.

Carpenter, C.W., and S. Loveridge. 2019a. “Factors Associated with Latinx-Owned Business Survival in the United States.” The Review of Regional Studies, 49(1):73–97. Available at: https://rrs.scholasticahq.com/article/7933-factors-associated-with-Latinx-owned-business- survival-in-the-united-states.

Carpenter, C.W., and S. Loveridge. 2019b. “A spatial model of growth relationships and Latinx- owned business.” The Annals of Regional Science, 63(3):541–557. Available at: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00168-019-00942-x.

Carpenter, C.W., and S. Loveridge. 2020. “Business, Owner, and Regional Characteristics in Latinx-owned Business Growth: An Empirical Analysis Using Confidential Census Microdata.” International Regional Science Review, 43(3):254-285. Available at: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0160017619826278.

Economic Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. 2018. “Demographic Characteristics of Hired Farmworkers.” Available at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/farm-labor/

Gallardo, R., and B. Bishop. 2020. “An Immigration Ban Would Have Doubled Rural Population Loss.” The Daily Yonder. Available at: https://dailyyonder.com/an-immigration-ban-would-have-doubled-rural-population-loss/2020/04/22/.

Horst, M., Marion, A. Racial, ethnic and gender inequities in farmland ownership and farming in the U.S. Agric Hum Values 36, 1–16 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-018-9883-3

Jarmin, R.S., C.J. Krizan, and A. Luque. 2015. “Owner Characteristics and Firm Performance During the Great Recession.” U.S. Census Bureau Center for Economic Studies, Paper No. CES- WP-14-36. Available at: https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2572626.

Munoz, A. P., L.E. Browne, S. Carbonell, P. Chakrabarti, D. Green, Y.K. Kodrzycki, R.C. Walker, A. Steiger, and B. Zhao. 2011. “Small Businesses in Springfield, Massachusetts: A Look at Latino Entrepreneurship.” Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Community Development Discussion Paper, No. 2011-02. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1927522.

Munoz, J.M., and M.I. Spain. 2015. Hispanic-Latino Entrepreneurship: Viewpoints of Practitioners. New York: Business Expert Press.

Pisani, M.J., J.M. Guzman, C. Richardson, C. Sepulveda, and L. Laulie. 2017. “Small business enterprises and Latino entrepreneurship: An enclave or mainstream activity in South Texas?” Journal International Entrepreneurship, 15:295–323. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-017-0203-6.

Robles, B.J., and H. Cordero-Guzman. 2007. “Latino Self-Employment and Entrepreneurship in the United State: An Overview of the Literature and Data Sources.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political Science, 613(1):18-31. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716207303541.

Salinas, C., and A. Lozano. 2019. “Mapping and recontextualizing the evolution of the term Latinx: An environmental scanning in higher education.” Journal of Latinos and Education, 18(4):302–315. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/15348431.2017.1390464.

United States Hispanic Chamber of Commerce. (Web site). Available at: https://ushcc.com/local-chambers/.

Smith, R.A., and S.E. Mannon. 2020. Ethnic Entrepreneurship Without Ethnicity: Latino Entrepreneurs in Northern Utah. Sociological Spectrum, 33-47. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/02732173.2019.1710631.

Vallejo, J.A., and S.L. Canizales. 2016. “Latino/a professionals as entrepreneurs: how race, class, and gender shape entrepreneurial incorporation.” Ethnic and Racial Studies, 39(9):1637-1656. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01419870.2015.1126329.

The Economist. 2020. “Well documented - America’s guest-worker boom” January 18. Available at: https://www.economist.com/united-states/2020/01/18/americas-guest-worker-boom.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. 2019. Characteristics of the Foreign-Born Population by World Region of Birth.

1 This article uses the term “Latinx” as a gender-neutral label for Latinas/os and Latin@. See Salinas and Lozano (2017) for a discussion of the term.