Rural leaders must actively understand the demographic and economic forces that shape their local economy and workforce. By recognizing these shifting conditions, communities can better respond to economic opportunities and threats and position themselves for future success. Many factors contribute to rural prosperity, but the competitiveness of the local is particularly important. A skilled workforce enhances local business productivity, attracts and fosters new enterprises, and supports higher wages for workers.

This article focuses on two broad sets of issues that shape the rural workforce. First, it examines several demographic and health conditions that influence worker availability in rural regions. Second, it highlights the employment opportunities available to rural workers and how these opportunities have changed over time. Finally, it outlines several broad steps that rural communities can take to grow and strengthen their local workforce.

Over the past 15 years, many nonmetropolitan counties lost population due to an aging population and net domestic out-migration (Johnson, 2023). Since 2010, the number of older-aged counties—those with a population in which 20% of the total population is 65 years of age and older—has almost tripled (Farrigan et al., 2024). The aging population and subsequent loss of working-age residents has had significant consequences for the rural workforce. The Baby Boom generation is leaving the workforce, the Millennial generation is fully in the workforce, and Generation Z is smaller relative to these two other generations. As a result, more workers are leaving the rural workforce than entering it.

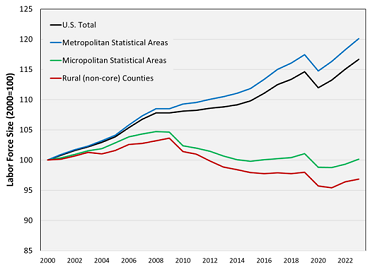

These factors, along with declining fertility rates, limit the current and future supply of available workers (Asquith and Mast, 2024). Figure 1 shows how the civilian labor force changed between 2000 and 2023. During thisperiod, the U.S. labor force grew almost 17% nationally and 20% in metropolitan counties. Urban regions, particularly in the Sun Belt, drove much of this growth. By contrast, the overall labor force declined in micropolitan (small urban counties with populations of 10,000 to 50,000 residents) and rural counties since the Great Recession. For many of these counties, the workforce is now smaller—in absolute terms—than it was 20 years ago.

These trends remain inconsistent throughout rural America, as some regions experienced more pronounced labor force declines than others. For instance, nonmetropolitan counties (micropolitan and rural counties) in Illinois—a state with both an aging population and significant net domestic out-migration—have lost 15% of their labor force since the beginning of the century. Other regions that experienced substantial labor force declines include the Mississippi Delta, the Southern Black Belt, Eastern Kentucky, and parts of the Great Plains. As a result, one reason rural employers find it increasingly difficult to find workers is that there are simply fewer workers available.

Nonmetro counties also have lower labor force participation rates, particularly for workers aged 25 and older (Sanders, 2023). Rural areas have greater disability rates due to higher incidences of smoking and obesity, lower levels of physical activity, more limited healthcare access, and, in some cases, higher risks from workplace hazards (Jones et al., 2009). Moreover, rising mortality rates—particularly among working-age, non-Hispanic whites—further limit labor force growth and availability. During the 1990s and 2000s, greater incidences of cardiovascular disease and cancer (often due to a lack of screening) caused higher increased mortality rates in rural counties. However, since the 2010s, increases in metabolic and respiratory diseases, suicide, substance abuse, and other mental and

behavioral disorders have led to higher mortality rates (Monnat, 2020). A recent USDA Economic Research Service study showed that rural health disparities, particularly the mortality gap, have increased significantly over time. In 1999, the natural-cause mortality rate for the prime working-age population in rural areas was 6% higher than that in urban areas, but the difference had grown to 43% in 2019 (Thomas, Dobis, and McGranahan, 2024). These challenges persist in the post-pandemic world, as rural regions continue to have older populations, poorer health, and lower COVID vaccination rates (Sun and Monnat, 2022). Therefore, the growing mortality gap and higher disability rates, particularly among working-age residents, leave many rural regions with relatively fewer available workers.

Given these demographic challenges, migration will dictate future labor force growth in many rural regions (Asquith and Mast, 2024). However, migration can often present more challenges than opportunities. Many rural counties continue to experience net domestic out-migration, particularly from young people who leave theirhometowns to pursue post-secondary education, join the military, start professional careers, or begin families (Carr and Kefalas, 2009). This “brain drain” can create a vicious cycle, where the perceived lack of opportunities and amenities can motivate people to leave rural communities, leading to smaller populations, fewer work opportunities, diminished tax bases, and reduced funding for public schools.

The pandemic somewhat disrupted these trends. Greater virtual and hybrid work opportunities enabled movement away from dense urban areas into more suburban and exurban counties (Frey, 2023). Some nonmetro counties, particularly those in recreation-dependent areas, experienced net domestic in-migration during the pandemic’s first year, reversing the trends of the previous decade. However, in many nonrecreational rural counties, this net positive migration was more a result of the pandemic keeping people in place rather than new residents moving into rural counties (White, 2023).

Although recent graduates are emblematic of rural brain drain, not all young people have the same propensity to leave the state where they received post-secondary education. The U.S. Census Bureau’s Post-Secondary Employment Outcomes (PSEO) dataset utilizes information from public universities, state education departments, state labor market agencies, and the Census Bureau to show where graduates from public colleges and universities find work after graduation. These data show, for instance, that post-secondary graduates with degrees in education and healthcare are more likely to stay in the state where they went to school than students who study STEM fields such as engineering or computer science.

Migrants—both domestic and international—contribute to the rural workforce in different ways. For example, Deller, Kures, and Conroy (2019) found that the benefits of retirement migration (from both pre-retirees and retirees) can offset the loss of younger adults often associated with rural brain drain. This is particularly true for older (aged 55+) migrants with entrepreneurial ambitions. Migrants who can take advantage of remote and hybrid work arrangements are more likely to be well-educated, work in professional services, and earn higher incomes (Hughes, Willis, and Crissy, 2022).

Rural employers—particularly in sectors such as agriculture and manufacturing—also rely heavily on immigrant workers. Beyond filling low-wage jobs, many immigrant communities provide an important source of entrepreneurial energy (Carpenter and Loveridge, 2021). Immigrants are also needed to fill many critical high-skill positions in rural communities. For instance, foreign doctors make important contributions to the rural healthcare workforce, where a shortage of medical professionals can limit the availability of basic medical services (Braga, Khanna, and Turner, 2023). Just as these immigrant populations support these industries, their families also bolster enrollment in rural schools, helping these schools remain open and avoid greater consolidation.

Many rural communities try to encourage former residents to return home, but many factors can influence these residential decisions. Cromartie, von Reichert, and Arthun (2015) attended high school reunions throughout the Midwest and Great Plains to interview stayers, leavers, and returnees to better understand their motivations. They found that family considerations often drew people back to their hometowns, but they had to be able to find suitable employment opportunities to make these moves possible. Former residents were also attracted by shorter commutes, lower living costs, outdoor amenities, and a small-town community feel. Returnees often have higher levels of educational attainment and hold professional careers as doctors, managers, engineers, teachers, or entrepreneurs. Those who would not consider returning to their rural hometowns cited factors such as financial and career sacrifices, excessive familiarity, and the lack of cultural amenities.

Over the past decade, emerging factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the rise of remote work have increased opportunities to move and changed how people make residential decisions. In a survey of residents in rural northwest Missouri, Low, Rahe, and Van Leuven (2023) found that the pandemic had changed people’s attitudes toward rural living, particularly in low-amenity regions. Their survey showed that return migrants to northwest Missouri exhibited a desire for greater proximity to their families. Return migrants also exhibited an increased preference for rural living, especially among self-employed residents and those seeking a strong sense of belonging. That said, friend and familial linkages may weaken over time, so relying on them to attract return migrants may not prove sustainable.

High-amenity areas show different trends. Since the pandemic, “Zoom towns” or “gateway” cities have been attracting skilled and mobile workers with outdoor amenities, a small-town feel, and broadband infrastructure. However, this influx of new residents can create significant growth challenges related to housing affordability and availability, congestion, and a rising cost of living (Stoker et al., 2021). In these communities, local residents working in relatively low-paying service industries struggle to keep up with the rising cost of living. If retirees drive the population growth in these communities, they face the challenge of growing their population without expanding their workforce. As a result, domestic in-migration does not necessarily solve the workforce challenges faced by many rural communities and may, in some instances, create new challenges.

The availability of quality job opportunities is crucial for rural regions to attract and retain workers (Cromartie, von Reichert, and Arthun, 2015), but rural job opportunities often differ from those in urban areas. Jobs in urban areas tend to be more knowledge-intensive and higher-paying in professional services, whereas those in rural areas are more often linked with government, manufacturing, and agriculture. There are also disparities in job quality and earning potential. For instance, Kim and Waldorf (2023) found that rural workplaces are associated with lower wages and that women—especially in low-paying jobs—face a higher wage penalty than men. Even though the gender wage gap is narrower for early-career workers compared to older workers, minor annual wage disparities can lead to significant wealth gaps over a lifetime.

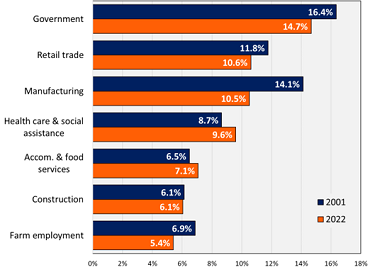

The type of jobs available to rural workers has changed over time. Figure 2 shows how employment in nonmetro U.S. counties shifted across several selected sectors between 2001 and 2022. During this period, nonmetro counties lost jobs (in both absolute and relative terms) in large sectors like government and manufacturing. Government remains the largest employing sector in nonmetro U.S. counties, accounting for almost 15% of total employment, mostly in state and local government activities such as local schools, prisons, and other public services. Between 2001 and 2022, nonmetro counties lost about 145,000 government jobs and nearly 650,000 manufacturing jobs. Manufacturing now represents just over 10% of all jobs in nonmetro counties, down from 14% in 2001. Conversely, healthcare employment grew during this period due to increasing demand from an aging population.

The changing mix of jobs creates challenges for rural regions because jobs created in growth sectors do not always align with the skills of workers from declining sectors. Manufacturing jobs typically offered family-sustaining wages for workers without significant post-secondary education, but displaced manufacturing workers often lack the skills required for similarly paying healthcare jobs. Additionally, men fill most manufacturing jobs, but women represent the overwhelming majority of the healthcare workforce. This is not to say that workers cannot make these transitions, but they are not quick or easy. Smaller sectors have created additional employment opportunities, in sectors such as real estate (through services such as Airbnb and Vrbo) and transportation (through services such as Uber and Lyft), but these opportunities often provide supplemental income rather than full-time employment.

More diversified economies, with a balanced mix of jobs, industries, and multiple specializations, can help rural communities better navigate economic shocks and transitions (Slack and Monnat, 2024). Over the past half century, many farm-dependent counties have been forced to adjust to the changing economy. Farm employment has declined by 35% nationwide since 1969, leading farming-dependent communities to rely more on other industries for job opportunities (White and Van Leuven, 2023).

A recent CoBank report showed that off-farm sources accounted for approximately 80% of total farm household income (Spell et al., 2022). This off-farm income comes not only from spousal jobs: 56% of principal farm operators had a primary job off the farm in 2017. These additional economic opportunities allow farmers and their families to generate extra income and secure benefits like health insurance. However, all rural communities—not just those in farm-dependent regions—need diversified economies. Local economic development goals should focus on establishing and supporting multiple sources of economic growth to mitigate risks and create new opportunities rather than pursuing diversity for its own sake (Feser et al., 2014).

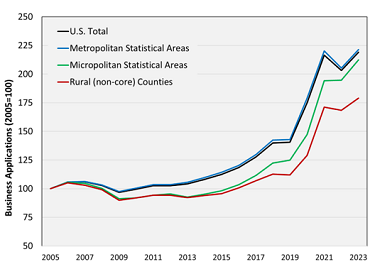

In light of the changing rural economy, many rural workers seek to create their own opportunities. Entrepreneurship allows rural workers to create their own jobs or generate enough supplemental income to support themselves and their families. One positive trend emerging from the pandemic is the growing interest in entrepreneurship in both urban and rural regions. The U.S. Census Bureau’s Business Formation Statistics captures this rapid increase in entrepreneurial activity. Figure 3 shows that nationwide, the number of business applications has more than doubled since 2005. This trend includes rural counties, where business applications are up over 75%, with most of this increase occurring since 2019. Even though most business applications do not result in a new business, they serve as a proxy for people’s interest in starting their own business.

Entrepreneurs have many different motivations and come from various groups. Necessity drives some entrepreneurs, while opportunity motivates others. In a rural context, there are clear differences between counties with low and high per capita incomes; entrepreneurship is more driven by necessity in the former and opportunity in the latter (Conroy and Low, 2021). Moreover, entrepreneurs come from diverse backgrounds, and many of these groups—women, immigrants, and disadvantaged communities—should not be overlooked. They can also span many generations. For instance, Deller, Kures, and Conroy (2019) found that older entrepreneurs (including retirees and pre-retirees) often provide essential human, financial, and business capital that can be utilized to start new ventures or invest in rural businesses. Overall, self-employment and entrepreneurship make positive contributions to regional economic well-being (Rupasingha and Goetz, 2011) and enable rural workers to stay in their communities.

In addition to the issues discussed above, many other factors shape the rural workforce, such as secondary and post-secondary educational opportunities, racial and ethnic diversity, and socio-economic inequities (Slack and Monnat, 2024). Therefore, no single strategy can build and strengthen the rural workforce. Rather, rural regions must adopt multiple strategies and make long-term commitments to address these challenges. Among others, rural regions must:Create places where people want to live. Migration is critical to growing the rural workforce, both in terms of attracting new residents and retaining existing residents. As a result, rural communities must create places that offer high quality of life. Quality of life considerations are in the eyes of the beholders in terms of natural or cultural amenities. However, all communities must pay attention to issues such as school quality, housing availability and affordability, and access to healthcare, eldercare, and childcare (Farrigan et al., 2024). Similarly, attractive communities also offer quality broadband, clean water, and good roads. Declining populations and diminished tax bases, however, can restrict the ability of rural communities to meet these needs.

Connect young people to career and work opportunities. Building and sustaining the rural workforce requires connecting local youth to beneficial (rather than exploitative) work opportunities. This is particularly important for rural communities experiencing out-migration and population loss. Private sector and education leaders can better prepare local youth for the world of work by engaging them through career exploration, work-based learning, career and technical education, internships, and apprenticeship opportunities (Ross et al., 2020). Moreover, connecting young people to local employers can further establish the personal and professional relationships that can help keep them within their community.

Connect entrepreneurs to available resources and support: In light of the post-pandemic surge in entrepreneurial energy, we must recognize that there is no turnkey strategy for promoting entrepreneurship and creating new businesses. Rather, we must introduceyoung people to entrepreneurial opportunities, recruit entrepreneurs to rural regions, and connect local entrepreneurs to existing support services. Given the diversity of entrepreneurs and their motivations, support services must meet the scale, format, and languages that entrepreneurs need to launch their venture and grow their business. However, the continuous need to strengthen and expand the broadband infrastructure will be critical for rural entrepreneurs, particularly those operating home-based businesses or those without a storefront.

Diversify rural economies: Diverse economies depend less on single firms or industries and are therefore better positioned to weather economic shocks. However, economic diversity should not be a goal unto itself. Rather regions must continuously seek to establish and support multiple sources of economic strength to create new opportunities and mitigate risk (Feser et al. 2014). Entrepreneurship can play an important role in this process. Not only can entrepreneurs create new businesses and job opportunities, but greater local ownership and control can help rural communities exert more control over their economic trajectory. In sectors like manufacturing, independent and smaller plants have shown to be more likely to survive economic downturns than externally owned, multi-plant firms (Low and Brown, 2017).

Rural leaders must continuously work to understand the demographic and economic forces that shape their local economy and workforce. This knowledge will enable them to better detect and respond to economic opportunities and threats. This in turn will allow them to develop strategies that strengthen and diversify their economies and prepare their workforce for the future.

Asquith, B.J., and E. Mast. 2024. “The Past, Present, and Future of Long-Run Local Population Decline.” Policy and Research Brief. W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. Available online: https://doi.org/10.17848/pb2024-76

Braga, B., G. Khanna, and S. Turner. 2023. “Migration Policy and the Supply of Foreign Physicians: Evidence from the Conrad 30 Waiver Program.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 32005.

Carpenter, C.W., and S. Loveridge. 2021. “Can Latinx Entrepreneurship Help Rural America?” Choices 36(4).

Carr, P.J., and M.J. Kefalas. 2009. Hollowing Out the Middle: The Rural Brain Drain and What It Means for America. Beacon Press.

Conroy, T., and S. Low. 2021. “Opportunity, Necessity, and No One in the Middle: A Closer Look at Small, Rural, and Female-Led Entrepreneurship in the United States.” Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy 44:162–196.

Cromartie, J.B., C. von Reichert, and R.O. Arthun. 2015. Factors Affecting Former Residents' Returning to Rural Communities. USDA Economic Research Service, Economic Research Report ERR-185.

Deller, S., M. Kures, and T. Conroy. 2019. “Rural Entrepreneurship and Migration.” Journal of Rural Studies 66:30–42.

Farrigan, T., B. Genetin, A. Sanders, J. Pender, K.L. Thomas, R. Winkler, and J. Cromartie. 2024. Rural America at a Glance: 2024 Edition. USDA Economic Research Service, Economic Information Bulletin EIB-282.

Feser, E., T. Mix, M. White, K. Poole, D. Markley, and E. Pages. 2014. Economic Diversity in Appalachia: Statistics, Strategies, and Guides for Action. Appalachian Regional Commission. Available online: https://www.arc.gov/report/economic-diversity-in-appalachia/

Frey, W. 2023. Pandemic-Driven Population Declines in Large Urban Areas Are Slowing or Reversing, Latest Census Data Shows. Brookings Institution.

Hughes, D.W., D. Willis, and H. Crissy. 2022. “What Does COVID-19 Mean for the Workplace of the Future?” Choices 37(3).

Johnson, K. 2023. “Population Redistribution Trends in Nonmetropolitan America, 2010 to 2021.” Rural Sociology 88(1):193–219.

Jones, C., T. Parker, M. Ahearn, A. Mishra, and J. Variyam. 2009. Health Status and Health Care Access of Farm and Rural Populations, USDA Economic Research Service, Economic Information Bulletin EIB-57.

Kim, A., and B.S. Waldorf. 2024. “Unpacking the Gender Wage Gap in the U.S.: The Impact of Rural Employment, Age, and Occupation.” Journal of the Agricultural and Applied Economics Association 3(4):706–723.

Low, S.A., and J.P. Brown. 2017. “Manufacturing Plant Survival in a Period of Decline.” Growth and Change 48(3):297–312.

Low, S., M. Rahe, and A. Van Leuven. 2023. “Has COVID-19 Made Rural Areas More Attractive Places to Live? Survey Evidence from Northwest Missouri.” Regional Science Policy and Practice 15(3):520–541.

Monnat, S.M. 2020. “Trends in U.S. Working-Age Non-Hispanic White Mortality: Rural-Urban and Within-Rural Differences.” Population Research and Policy Review 39:805–834.

Ross, M., R. Kazis, N. Bateman, and L. Stateler. 2020. “Work-Based Learning Can Advance Equity and Opportunity for America’s Young People.” Brookings Institution. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/work-based-learning-can-advance-equity-and-opportunity-for-americas-young-people/

Rupasingha, A., and S.J. Goetz. 2011. “Self-Employment and Local Economic Performance: Evidence from U.S. Counties.” Papers in Regional Science 92(1):141–161.

Sanders, A. 2023. “Rural Employment and Unemployment.” USDA Economic Research Service. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/employment-education/rural-employment-and-unemployment/

Slack, T., and S.M. Monnat. 2024. Rural and Small-Town America: Context, Composition, and Complexities. University of California Press.

Spell, A., K. Jacobs, S. Low, and J. Krohn. 2022. “The Importance of Off-Farm Income to the Agricultural Economy.” CoBank. Available online: https://www.cobank.com/knowledge-exchange/general/the-importance-of-off-farm-income-to-the-agricultural-economy

Stoker, P., D. Rumore, L. Romaniello, and Z. Levine. 2021. “Planning and Development Challenges in Western Gateway Communities.” Journal of the American Planning Association 87(1):21–33.

Sun, Y., and S. Monnat. 2022. “Rural-Urban and Within-Rural Differences in COVID-19 Vaccination Rates.” Journal of Rural Health 38:916–922.

Thomas, K.L., E.A. Dobis, and D.A. McGranahan. 2024. The Nature of the Rural-Urban Mortality Gap. USDA Economic Research Service, Economic Information Bulletin EIB-265.

White, M. 2023. “Post-Pandemic Population Trends in the North Central United States.” farmdoc daily 13(84). Available online: https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2023/05/post-pandemic-population-trends-in-the-north-central-united-states.html

White, M., and A. VanLeuven. 2023. “Changes in Farm Employment, 1969 to 2021.” farmdoc daily 13(130). Available online: https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2023/07/changes-in-farm-employment-1969-to-2021.html