In the midst of national healthcare debates, there has been little discussion of how health, healthcare costs and access, and health insurance fit into national agriculture policy efforts to build a more vibrant and resilient farm economy. Yet Inwood (2015) found that 65% of commercial farmers identified the cost of health insurance as the most serious threat to their farm, more significant than the cost of land, inputs, market conditions, or development pressure. In order to grow the next generation of farmers and increase rural prosperity, there is a need to understand how healthcare costs, access, and insurance affect both agriculture and rural development.

Responding to the shrinking and aging farm population, Congress has broadened approaches to stimulating growth and innovation in the food and agriculture sector through recent Farm Bills by including added funding for new and beginning farmer and rancher programs. Along with increasing access to markets, capital, and land, many programs focus on building human capital in the farm sector through training and education. These rural and workforce development programs have not, however, considered how health insurance influences these initiatives or the role of health insurance as a salient tool for supporting rural economic development.

In 2011 and 2015, the USDA included questions about health insurance on the Agriculture Resource Management Survey (ARMS). The ARMS data track overall numbers of farmers insured and their source of coverage. Yet, outside of Ahearn, El-Osta, and Mishra (2013) and Ahearn, Williamson, and Black (2015), there has been little discussion or analysis of how health, health insurance, or access to healthcare affect farm management decision-making and rural development. The authors of this paper are members of the national USDA-NIFA-funded project Health Insurance Rural Economic Development and Agriculture (HIREDnAg). The goal of this national research and Extension project is to understand how health insurance affects economic development and quality of life in the agriculture sector. We present new research findings examining health insurance access and use in the farm population and connections between health insurance and risk management, farm viability, and farmland access. We also discuss implications of this research on efforts to grow the next generation of farmers and ranchers and on rural economic development.

The research presented here is based on data from farmers and ranchers (hereafter farmers) collected in 10 case study states across the United States, including: California, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Michigan, Mississippi, Nebraska, Pennsylvania, Utah, Vermont, and Washington. Study states are located in each USDA region of the country (Northeast, North Central, South, West). State flexibility in implementing 2010 federal health insurance reforms introduced through the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) created discrete policy environments. States had the option to expand Medicaid and to establish state or federal health insurance exchanges, also known as marketplaces. Within each region, we paired states based on whether or not they chose to expand Medicaid (Figure 1).

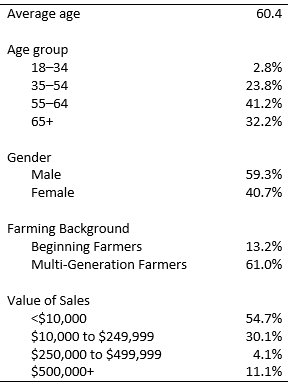

Using a mixed-methods approach, we conducted in-depth interviews with up to 10 families in each case study state in 2015–2016 and surveyed randomly sampled producer households in these states in 2017, yielding 1,062 responses. Mixed-methods research that includes both qualitative and quantitative methods offers better crosschecking and triangulation of data (Guba and Lincoln, 1981) and ensures the reliability and validity of analysis (Janesick, 1994). Survey and interview questions focused on healthcare and health insurance access, off-farm work, farm finances and economics, and farm labor. To ensure that our sample was representative of the national farm population, we weighted the sample on reported sales data to match sales proportions reported in the 2012 Census of Agriculture for the national farm population (Table 1). We present both the quantitative and qualitative data and include quotes that reflect common themes expressed by farmers in both the interviews and written survey comments.

Partly because of off-farm work, farmers have historically had overall high rates of health insurance (Ahearn, Williamson, and Black, 2015). Findings from the USDA’s 2015 Agricultural Resource Management Survey (ARMS) found that farmers are just slightly more likely to be uninsured than the general population (10.7% vs. 9.1%); dairy farmers are the most likely to be uninsured because they are most likely to farm full time and therefore less likely to have off-farm employment (Prager, 2016). Similar to the ARMS data, the majority of farmers in our survey sample (92%) reported that they and their families had health insurance in 2016. The way farm families are insured, however, is complex and varies by their age and life stage, health, values, and the structure of the enterprise.

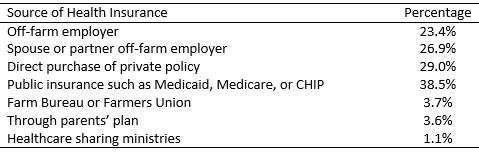

In the survey sample, 32% of farmers reported two or more health insurance plans within the same family. For example, one Nebraska farm family of four had insurance plans from three different sources: employer-based insurance for one adult, marketplace-purchased insurance for the other adult, and Medicaid (Children’s Health Insurance Program, CHIP) for both children. Half (50%) of the farm families had health insurance through an off-farm employer, 38% had a public health insurance plan (Medicaid, Medicare, or CHIP), and 29% purchased a private policy. Smaller percentages of farmers purchased a plan through a farm organization (3.7%), were on their parents’ plan (3.6%), or enrolled in a healthcare sharing ministry (1.1%) (Table 2).

Health insurance options vary with age and income of individual family members and can change during life events and transitions, such as leaving a parent’s insurance, change in marital status, or changes in off-farm employment. For example, a Utah rancher shared, “I had good health insurance through my wife’s employer. I lost it when we got divorced.” Among older farmers, it is common for one family member to be on Medicare while their younger spouse, not yet eligible for Medicare, has an employer-offered plan or a state or federal health insurance marketplace plan. Older farmers frequently reported delaying healthcare until they were eligible for Medicare at age 65. As a farmer from Michigan explained, “Once we hit 65 everything was taken care of.” While changes in health insurance due to life course changes are not unique to farm families, farming is a physical occupation, and physical health is a prerequisite for the business to operate. Farming ranks among the most dangerous occupations in the United States (CDC, 2013), and the injury rate for agricultural workers is 40% higher than the rate for all workers (BLS 2011), reinforcing the need to understand how health, access to healthcare, and the farm business are connected.

Fourteen percent of farmers reported they had transitioned from employer-based insurance options into the marketplace or enrolled in a public health insurance plan in the last five years. A provision of the ACA uses income and not assets to determine Medicaid and Marketplace subsidy eligibility (Andrews, 2013). This provision decouples the family from the assets of the enterprise and addresses the “land rich, cash poor” conundrum farmers often face. A Vermont dairy farm family was surprised to find they were eligible for expanded Medicaid; they explained that “we met with the assistor who looked at our [net] income, and we qualified… [I]t was the first time we had health insurance.”

About one out of five farmers (19%) of farmers shared that marketplace health insurance options available after 2010 allowed them to sign up for health insurance for the first time. For example, a ranch family with five children explained how ACA health insurance legislation changed their access to healthcare. Their three oldest children had never gone to the doctor because they had no health insurance. After the ACA implementation, the two younger children had preventative well-child visits and the family had access to a wider range of health services.

In 2016, 8% of our sample had no health insurance. These farmers shared that marketplace plans were unaffordable to them for two reasons. Some reported the premiums were unaffordable, while for others the cost of using the plan was too high due to high deductibles and out-of-pocket costs. These farmers still reported prioritizing their health by being cautious with their bodies, going for chiropractic care, bartering for healthcare, or using food as medicine.

As a cost-saving strategy, coupled with personal convictions, a small percentage of farmers (1.1%) reported enrolling in healthcare sharing ministries or faith-based healthcare plans as alternatives to buying health insurance. These plans do not cover preventive health services, but serve as a risk management strategy by providing catastrophic coverage. As such, some farmers reported delaying preventative care for themselves and their families that was not covered. The plans potentially inhibit access to care until a health issue becomes acute and expensive to treat. Some farmers shared how they continued to rely on public healthcare access through programs like subsidized vaccinations. A Michigan farm family with a large grain operation and enrolled in a faith-based plan reported relying on the local county vaccine program for their children, while a Michigan fruit grower shared, “I have a Christian Managed Health Care Account. I need a shingles vaccine. They don’t cover it. I’ll wait two years till I’m 65 and then Medicare will cover it.”

Farming is an inherently risky and dangerous occupation, and many farmers view health insurance as part of their risk management strategy. Three out of four famers surveyed (74%) reported that health insurance is an important or very important risk management strategy. As one farmer from Kentucky shared, “You have to have insurance. We have a risky job.” Another farmer from Mississippi said, “Show me a farmer who is not injured.” Nonfatal injuries and work-related illnesses can result in lost work time and permanent impairment that reduce farm productivity and profitability.

The health and well-being of all farm family members directly impact the farm enterprise. The farm enterprise and farm family are often treated as separate, but the two are intertwined. Two out of five farmers (40%) reported that they or a family member had health problems affecting their ability to farm. In addition, 50% reported they would have no one to run the farm in the case of a major illness or injury. These findings demonstrate the way in which health creates constraints on the farm operation with direct implications for enterprise growth and development. Current farm risk management programming predominantly focuses on production and marketing related risks and currently places little emphasis on health risk outside of farm safety. These findings reinforce the need for more active integration of health into business and risk management planning.

The finances of farm operations and farm families are often co-mingled, and healthcare costs can influence the trajectory of the farming enterprise. Greater than two-thirds (64%) of farmers reported that they were not confident they could pay the costs of a major illness or injury such as a heart attack, cancer, or loss of limb without going into debt. Moreover, 53% reported they were concerned they would have to sell up to the entirety of their farm assets to address health-related costs such as long-term care, nursing home care, or in-home health assistance.

Nationally, farmers have an average age of 58.3 years, and an aging population is more prone to health conditions that require costly care. Two-thirds (64%) of farmers in the survey sample reported having a pre-existing health condition. Taken together, these results indicate that to cover healthcare needs, older farmers may need to farm longer to augment their incomes or sell land to the highest bidder, which may result in nonfarm development and exacerbate the land-access bottleneck for young and beginning farmers. This further disrupts efforts to attract young farm families, as aging farmers persist in their occupations past the window of opportunity for their children and other young farmers to succeed them.

The Farm Bill supports new and beginning farmers through strategic investments in production, marketing, access to capital and land, and succession planning but does not address health insurance. The Young Farmer Coalition cites health insurance as one of the top three issues affecting the trajectory and success of young and beginning farmers (Shute, 2011). Examining macro-level data, Ahearn, Williamson, and Black (2015) and Bubela (2016) expected farmers would have little incentive to purchase a health insurance plan in the marketplace because of the burden of high costs on a young and beginning farmer’s operation. We found, however, that access to affordable health insurance through marketplace subsidies and Medicaid expansion has benefitted young farmers, especially in Medicaid expansion states.

Among young farmers, 18 to 34, over 11% report purchasing a policy from the health insurance marketplace, and almost half (41%) enrolled in a public health insurance program (Medicaid, TRICARE, or CHIP). Young and beginning farmers who purchased health insurance plans in the marketplace were able to take advantage of the available income-based subsidies, as one young farmer from Massachusetts explained, “It is cheaper for me to purchase a Silver plan in the marketplace than to go without health insurance and pay the penalty. And I really like having health insurance.” A young diversified farming couple in Vermont explained, “This insurance [Medicaid] means I can keep farming, it reduces the risk of farming for me and I don’t worry as much about being in a really risky occupation hard on my body.” Marketplace and expanded Medicaid have provided more health insurance options for young farmers in the early phase of their business cycle. By removing the need for a full-time off-farm job with benefits, farmers reported being able to invest more time and money into growing their operation.

Affordable and accessible health insurance options were especially significant for families who prioritized health insurance coverage for their children. Farm families shared the conflicting insurance options they face: 1) Famers can insure their families through an off-farm job, which takes time and energy away from the enterprise, or 2) depending on income, children may qualify for state-run CHIP health insurance; however, parents may remain uninsured or underinsured. Some farm families reported deferring job opportunities that would offer extra income and cash flow because the added earnings would increase their income above the threshold eligibility for public health insurance, but income levels would still be relatively low, making marketplace health insurance options unaffordable. This suggests that policies and programs aiming to build a young vibrant farm population can be strengthened by accounting for how health insurance factors into young and beginning farmer’s business plans and family needs.

In this sample, the majority (72%) of farmers 18–64 years old reported having full-time, part-time, or temporary off-farm work for additional income and access to health insurance. Understanding the relationships among types of jobs (e.g., salary, hourly), employers (e.g., public, private, nonprofit), and benefit packages that are supporting farm families is critical to understanding their effect on the farm business and rural economic development. While off-farm work provides an important source of income, cash flow, and health insurance, it also takes time and energy away from the farm enterprise and family and is an added source of tension and distraction. One multigeneration rancher commuting to a full-time off-farm job 45 minutes away articulated this challenge faced by many farmers:

We really would love it if we didn’t have to worry about me having a full-time job for insurance so that we could just farm and ranch. We would be okay on the farm without my full-time job, but you have to have it for the insurance. …you’d get more done so you’re not doing everything in the dark at 11 o’clock at night. I’m a believer that my family would have been a little better off if I was just working part time.

The stress of off-farm work is compounded by lack of high-paying employers offering health insurance and benefits in rural areas and shapes how farmers balance farm priorities with off-farm employment demands. In our interviews, farmers consistently pointed out the stress of commuting long distances to work, farming, and family obligations and the additional stress of performing well at their job to ensure they would not be fired or let go and lose their benefits.

As noted earlier, even farm families with employer-based insurance reported that individual family members are insured through different plans. In this survey, 46% of farmers were insured through public-sector jobs (health, education, government) compared to 36% in the private sector, and 20% in the nonprofit sector. In rural areas, public-sector jobs tend to offer the highest wages and most generous benefits. Changes in public- and private-sector employment options and benefits affect the financial stability and social well-being of farm families with impacts felt throughout rural communities.

Another challenge some farmers noted is the lack of physical access to healthcare resulting from rural hospital closures. Several farmers reported the consolidation of rural healthcare facilities, resulting in longer distances to travel for services. Employers prefer to locate in communities with high-quality healthcare services leaving rural communities without strong healthcare systems at a disadvantage in attracting new businesses offering quality jobs (Pender, Marré, and Reeder, 2012). Rural development programs embedded in the Farm Bill need to account for these emerging trends when creating programs and developing incentives for rural economic development.

Health insurance is a cross-sector risk for agriculture, interconnected with farm risk management, productivity, health, retirement, need for off-farm income for farmers of all ages, and land access for young and beginning farmers. In our survey, farmers expressed a preference for national health insurance policy to address specific needs of the farm sector. Three-quarters of farmers (74%) believed that the USDA should represent their unique needs in national health insurance policy discussions.

The 2018 Farm Bill presents a new opportunity to integrate health, access to healthcare, healthcare costs, and health insurance into the Risk Management Agency (RMA) and Rural Development (RD) initiatives that work to promote a vibrant and resilient farm sector. RMA programs traditionally focus on crop insurance as a way to manage risk, but there is an opportunity to expand how risk is framed to include health, healthcare costs and access, and health insurance. Moreover, there is an opportunity to account for age-specific health insurance needs that change along the life course by accounting for the varying needs of young farm families with young children, those who are middle-aged, and those over 65. The USDA has made substantial efforts to recruit a new generation of farmers and ranchers. To ensure returns on this investment, it is critical to consider the interplay between national farm policy and healthcare policy. RD initiatives could account not only for the number of jobs created in rural areas but also the quality of those jobs, including the provision of health insurance benefits, to support efforts to build a more vibrant and prosperous farm sector and rural economy. Including the ARMS health insurance questions on the Census of Agriculture would allow researchers and policy-makers to track changes over time and respond better to producer health policy and program needs.

Ahearn, M.C., J.M. Williamson, and N. Black. 2015. “Implications of Health Care Reform for Farm Businesses and Families.” Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy 37(2):260–286.

Ahearn, M.C., H.S. El-Osta, and A.J. Mishra. 2013. “Considerations in Work Choices of U.S. Farm Households: The Role of Health Insurance.” Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 38(1):19–33.

Andrews, M. 2013. “Income, Not Assets, Will Determine Subsidies in Online Insurance Marketplaces.” Kaiser Health News Network. Available online: http://khn.org/news/070213-michelle-andrews-answers-readers-questions-on-assets-and-student-health-plans/

Bubela, H.J. 2016. "Off-Farm Income: Managing Risk in Young and Beginning Farmer Households." Choices 2016(3).

Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor. 2011. Number and rate of fatal occupational injuries, by industry section. 2011. Available online: http://www.bls.gov/iif/oshwc/cfoi/cfch0010.pdf.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2013. “Agricultural Safety.” Workplace Safety & Health Topics. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/aginjury/.

Guba, E., and Y. Lincoln. 1981. Effective Evaluation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Inwood, S. 2015. “Opportunities for Extension: Linking Health Insurance and Farm Viability.” Journal of Extension 53(3): 3FEA1.

Janesick, V.J. 1994. “The Dance of Qualitative Research Design.” In N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln, eds., Handbook of Qualitative Research Design. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, pp. 209–219.

Pender, J., A. Marré, and R. Reeder. 2012. Rural Wealth Creation Concepts, Strategies, and Measures. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, Economic Research Report 131, March.

Prager, D. 2016. Health Insurance Coverage. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/farm-household-well-being/health-insurance-coverage/

Shute, L. 2011. “Building a Future with Farmers: Challenges Faced by Young, American Farmers and a National Strategy to Help Them Succeed.” National Young Farmers Coalition. Available online: http://www.youngfarmers.org/newsroom/building-a-future-with-farmers-october-2011/