African Heads of State signaled a paradigm shift in the way in which governments engage with agriculture by signing the Malabo Declaration on Accelerated Agricultural Growth and Transformation for Shared Prosperity and Improved Livelihoods, signed June 2014. The Malabo Declaration recognized the need for systemic change in African agriculture and agricultural systems, including systemic change in the policies and institutions that facilitate private sector engagement and investment, among others. To ensure movement on this front, Malabo explicitly committed to and focused attention on mutual accountability as a critical concept and process for achieving this systemic change and accelerating transformation.

The underlying motivation for the Malabo Declaration is that progress has been made in reducing African poverty and hunger, but there is a long ways to go and African presidents want to accelerate progress. Globally there are 795 million hungry people. Hunger is most prevalent in Africa (Figure 1). The 23 million African primary age schoolchildren that are hungry represent more than 1/3 of the hungry schoolchildren globally. The prevalence of stunting among sub-Saharan children under five fell from 39.6% in 1990 to 23.2% in 2015, yet this indicates that nearly one in four children still suffer from chronic undernutrition that will likely affect their future productivity and earning potential (World Bank, 2016a). The annual cost of undernutrition in seven African countries ranged from 3.1% of gross domestic product in Swaziland to 16.5% in Ethiopia (Covic and Hendricks, 2016).

It is critically important to invest in agricultural research and production and in post-harvest food systems in order to accelerate agricultural growth processes. Agricultural growth including agro-processing is typically more inclusive than other growth processes, leading to greater poverty-reducing effects (Dorosh and Thurlow ,2014). At the global level the Sustainable Development Goals define the development agenda for the next 20 years. The first two goals, “no poverty” and “no hunger”, are achieved through sustainable and inclusive growth. Inclusive growth also reduces income inequality that has been linked to terrorism, with food insecurity acting as an exacerbating factor (Krieger and Meierrieks, 2016; Hendrix and Brinkman, 2013). Thus, by reducing the potential for terrorism, inclusive agricultural growth serves U.S. national geopolitical interests. Finally, growing African economies provide a growing market for U.S. goods and services. U.S. exports to sub-Saharan Africa totaled $17.8 billion in 2015, an increase of 75% from 2005, and included $1.8 billion in agricultural exports. Growing African incomes and populations all but guarantee a growing market for food products and provide ample opportunity for profitable investment throughout the food system and food value chains.

Investment opportunities in African agriculture are best understood within the larger context of the dynamics of African agriculture, including the concept of mutual accountability as one of the seven Malabo Declaration commitments. The current implementation of the mutual accountability processes in African agriculture provides potential entry points for private sector engagement in these processes.

Over the past 25 years, sub-Saharan governments have transitioned from policies detrimental to private-sector agricultural investment to an emerging recognition that the private sector must be a willing partner if development is to be successful. Most African countries were colonies until the 1960s, and upon independence promoted state-directed development policies including over-valued exchange rates and other policies that slowed agricultural development. By the 1980s governments were running unsustainable deficits. In the late 1980s and early 1990s ‘structural adjustment’ to budget solvency caused both a decline in the implicit taxation of agriculture, and recognition that governments by themselves could not kick-start development processes. Consequently, over the past two decades sub-Saharan agriculture has increasingly opened to the private sector and in some ways has become an outstanding performer.

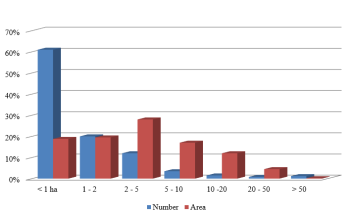

Source: Based on data available in Lowder, Skoet,

and Raney, 2016.

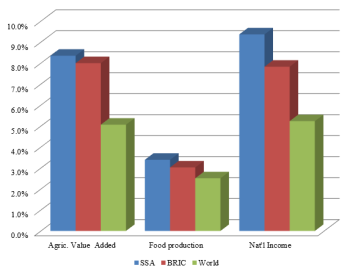

Source: World Bank, 2016b.

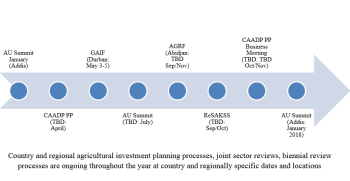

Source: Author’s compilation.

Africa has many agriculturally-based economies, comprising predominantly small-holder farmers. For poorer countries such as Rwanda and Madagascar as much as 75% of the labor force is employed primarily in agriculture. Even for emerging middle-income economies agriculture can remain the largest employer, for example, 45% of the labor force in Ghana is employed in agriculture. The overwhelming majority of these agricultural workers are smallholder farmers (Figure 2). 60% of sub-Saharan farmers own one hectare or less, and over 90% own five hectares or less. Most of these farms have very low crop yields, and most farm households have at least one person engaged in non-farm activities to generate additional income.

Food production in sub-Saharan Africa has increased at an annual average rate of 3.4% from 1996 to 2013 (Figure 3). This exceeds the population growth rate of 2.7%, and world food production growth of 2.5%. It also exceeds the food production growth of 3.0% in the BRIC countries—Brazil, Russia, India and China—that have been among the top destinations for private-sector investment over the past 20 years. Agricultural value added in sub-Saharan Africa grew at an annualized rate of 8.4% over the period 1996 to 2015, compared to 8.0% for the BRICs and 5.1% for the world. This agricultural performance had positive impacts on overall economic growth, with nominal sub-Saharan net national income increasing by an annualized 9.4% relative to 7.8% in the BRICs and 5.2% globally. Foreign direct investment in sub-Saharan Africa responded, increasing by 12.5% annually over the period to $42 billion in 2015, yet at 2.6% of African GDP remains below the global average of 2.9% (World Bank, 2016b).

While sub-Saharan Africa made progress over the past two decades in reducing poverty from 57.7% to 41.0% and the food deficit from 234 to 131 kcal/person/day; this fell short of the globally-endorsed Millennium Development Goal targets. In response both global and African leaders moved to accelerate agricultural growth and development. It is unusual in developing countries for presidents to pursue a common development agenda, but a unique set of factors contributed to this cooperation: The importance of agriculture, almost a decade of work initializing the Comprehensive Africa Agricultural Development Programme (CAADP) in 2003, and then over a decade strengthening CAADP as an institution that provides leadership and coordination to agricultural development across the continent. As a result, there is excellent coordination across leading African countries to accelerate agricultural development with a new approach centered on inclusive stakeholder involvement. This new approach is leading to unique opportunities.

In the Malabo Declaration, African Heads of State called on “the African stakeholders, including …private sector operators in agriculture, agribusiness and agro-industries… to rally behind the realization of the provisions of this Declaration and take advantage of the huge opportunities that it presents” (Malabo Declaration, IX.9.e). Countries implement their Malabo Declaration commitments guided by the Implementation Strategy and Roadmap to Achieve the 2025 Vision on CAADP. At the continental level CAADP is implemented by the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) that reports to the African Union’s Commissioner for Rural Economy and Agriculture. There are several emerging components of the overall CAADP process that are key to advancing mutual accountability: the CAADP ‘Round II’ National Agricultural Investment Plans (NAIPs II), the agricultural Joint Sector Review (JSR), and the African Union’s first biennial review. Figure 4 provides a timeline for these events. There are a number of related processes coordinated to some degree by CAADP that support implementation of Malabo Declaration commitments, including the African Green Revolution Forum, the Grow Africa Investment Forum, the Regional Strategic Analysis and Knowledge Support System annual conference, the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition, and the CAADP Partnership Platform meeting.

In addition to the political will to transform subsistence agriculture into a commercial food system, several additional factors indicate that African agricultural and food systems are likely to remain strong investment candidates. The region has high population growth and is projected to contain 1/4 of the world’s population by 2050, including a significant youth population in both rural and urban areas. Urbanization, income growth, and global changes in food value chains are also reflected in an increasingly competitive African food system. African consumers including the rural poor are rapidly increasing their consumption of purchased and processed foods. Growing supermarket chains are reaching into small cities and rural areas. In Ghana, a middle income country, urban consumers purchase 96% of their food and rural consumers 79% (Covic and Hendricks, 2016). Public and private grades and standards are improving food quality and opening up global markets, supported by changing trade regimes. In many ways, African agricultural and food systems represent ideal investment candidates.

Mutual accountability appeared in high-level global dialogs as a tool to manage for development results in the Paris Declaration, with expansion in the Accra Accord and as a fundamental principle in the Busan Partnership Agreement (OECD, 2011). The underlying concept as refined in the Malabo Declaration is that inclusive, agriculturally-led growth is a complex development process requiring both systemic and thematic change, and will work best when all stakeholders are aligned and contributing as well as benefitting. Mutual accountability is a process to improve alignment, contribution and accountability to accelerate inclusive growth for both individual and mutual benefit.

As being implemented in African agriculture, there are four essential components of an agricultural mutual accountability process:

African agricultural input supply issues provide an illustrative example of the potential of mutual accountability. Arguably the biggest technical impediment to African agricultural growth is low productivity stemming from limited smallholder adoption of improved inputs. A plethora of studies describe what smallholder characteristics influence adoption, but adoption remains low. Governments have implemented a variety of programs to increase adoption with limited success, for example, input subsidies often lead to significant increases in adoption while the subsidies last but dis-adoption after removal of the subsidies. An alternative approach is not to focus exclusively on the smallholder, but rather on the input distribution system including the smallholder. For example, smallholders may limit fertilizer purchases because of quality concerns, because fertilizer is not available at planting, because they may not be able to repay credit if yield response is diminished due to late delivery, poor rainfall or other issues. The private sector may not be able to deliver fertilizer on time due to government delays in approving import permits or opaque pricing regulations. Government may create regulations because it doesn't trust suppliers to deliver fertilizer on time, based on past experience, and has difficulty providing credit based on past experience of smallholder non-repayment. No single stakeholder can solve this problem. A potential solution comprises joint improvement of private sector delivery, farmer adoption and repayment, government policy and more effective government expenditure. This solution requires planning, coordinated commitments by multiple stakeholders to this plan, successful execution of these individual commitments that synergistically depend on successful execution of others' commitments, and sufficiency of the totality of actions to generate improved returns for all stakeholders that will drive interest in continuing improvements in the supply and adoption of modern agricultural inputs.

As many as 20 African countries have or are completing their first five-year NAIP, and per CAADP guidelines are preparing for their NAIP II plans in 2017. The first round of NAIPs delineated sector investment priorities for government with the target of allocating 10% of budgets to agriculture, and with the intention that donors would provide aligned investment. While the NAIPs delineated public investment needs and priorities, actual budget allocations and alignment varied by country. For example, Burkina Faso’s budget allocation to agriculture averaged 10.2% of its national budget from 2004 to 2011, which represents 8.2% of agricultural value added and 2.7% of national gross domestic product. This places Burkina Faso among the low-income countries most supportive of agriculture (Covic and Hendricks, 2016).

The African Union is seeking improvements in NAIP II processes that include greater transparency and inclusiveness as well as more reliance on data and evidence in dialog and decision making. Inclusiveness refers not just to inclusiveness among government line ministries and super-ministerial bodies, all of whom often affect how accurately budget expenditures reflect stated priorities, but also civil society and the private sector. Improved data and analytic systems can contribute to a more accurate dialog about the results frameworks or pathways to achieve a country’s vision for their agricultural and food system, which in turn helps bring greater coherence and alignment of actions to achieve that vision.

In terms of the plans themselves, the NAIPs II will include explicit roles for the private sector and civil society, following inclusive dialog with these groups in the preparation process. This is consistent with BPA guidance, including recognition that the private sector has a role to play in “advancing innovation, creating wealth, income and jobs, mobilizing domestic resources and in turn contributing to poverty reduction” (para 32) and therefore must “play an active role in exploring how to advance both development and business outcomes so that they are mutually reinforcing” (OECD, 2011 p. 10)

Another significant change from the first round is that the NAIPs II will include commitments to improve policy and improve systems for formulating and implementing policy. Better policy and deeper engagement in CAADP processes are both associated with faster African agriculturally-led growth and faster reductions in poverty particularly in the past decade. Further acceleration in agricultural growth is believed to require increased private sector investment. Hence the Malabo Declaration pledges “to create and enhance necessary [and] appropriate policy and institutional conditions and support systems for facilitation of private investment in agriculture, agri-business and agro-industries,” (African Union, 2014).

Finally, the African Union has asked countries to include in their NAIPs II a spending plan that both allocates budget funding according to NAIP priorities, and shows future funding and sources to reach the commitment of allocating 10% of national budgets to agriculture.

In sum, a NAIP II is the country’s organizing document that sets out country-owned priorities and guides stakeholder actions to accelerate the country’s agricultural growth. Regional Economic Communities engage in analogous processes to develop Regional Agricultural Investment Plans that are the organizing documents at the regional level.

Opportunities for private-sector engagement in national and regional agricultural planning will depend on the specifics of the country or regional processes and timing. NEPAD presented available country- and region-specific information at the CAADP Development Partner Coordination Group meeting held November 2016 in Addis Ababa.

The agricultural joint sector review (JSR) is a critical part of CAADP mutual accountability processes. The JSR is simultaneously a process, a product, and an event. In the past some countries have had joint sector reviews that focused on government financial accountability for funds spent in agriculture, and more recently included the proportion of the budget allocated to agriculture per the Malabo Declaration. Leading countries are now strengthening their JSRs to include reviews of sector impact on inclusive growth, increased trade, and reduced poverty and hunger, as well as the sector’s intermediate progress towards impact. The strengthened JSR also includes public commitment from all stakeholders to a national agenda, such as the country’s NAIP II plan, in specific and quantifiable ways that can be reported on at the following year’s JSR. It is important that actions specified in the NAIPs and the JSR commitments to these actions be SMART: specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound. New Alliance countries have some initial experience with soliciting commitments in their Cooperation Frameworks; the New Alliance experience, commitments and reporting are intended to become part of ongoing CAADP processes.

The most noticeable component of the JSR is the event—a high level, optic event reviewing the sector’s impact and progress and the stakeholders’ execution of their commitments, as well as public presentation of the plan and commitments for the upcoming year. This review is centered on a report(s) containing the relevant information on progress, commitments, and other topics as needed—this report is the JSR product. But none of this can take place without an ongoing JSR process. This process starts with the NAIP and the JSR commitments, and the actions taken to execute these commitments. Often these actions are processes in themselves, e.g. commitments to deliver inputs through farmers’ organizations—as an illustrative example—require a coordination process between private sector wholesalers and civil society in the form of the cooperative, possibly including the government as fertilizer importer and the financial community as creditors. The process includes documentation of what did and did not work so that adjustments can be made for next season. This leads into action-oriented dialog among multiple stakeholders to implement these improvements, for example in Rwanda, dialog between One Acre Fund and the Ministry of Agriculture led the public extension service to improve their agronomic recommendations based on One Acre Fund research. While least noticeable, the processes of ongoing actions by and interactions among stakeholders are perhaps the most important contributor to accelerated agricultural growth. Simultaneously, the more quantitative processes of data collection and analysis are ongoing throughout the year both to capture emerging trends and progress but also to respond to acute situations arising unexpectedly, all for use in the run-up to and reporting at the JSR event. Opportunities for private sector engagement in JSRs depends on country processes and timing.

The Malabo Declaration committed to a biennial review of progress towards successful implementation of Malabo. The first report will be prepared in 2017 for presentation at the African Union summit in January 2018.

The first biennial review will be largely focused on introducing the review process to countries and regional economic communities, and establishing baseline measurements of the current status of the Malabo Declaration commitments. NEPAD engaged expert consultants to delineate a subset of the annually reported CAADP indicators to be expanded and adapted specifically to address progress towards the commitments. A set of experts convened in Accra, Ghana in October 2016, to review indicators, and the final list contains 40 indicators representing the Malabo Declaration commitments and intermediate progress towards the commitments. The African Union will ask all countries to report on these indicators at a minimum.

The African Union with development partners over the next few months will delineate a scorecard with a subset of indicators that summarize the review results for presentation to African presidents at the January 2018 summit. This scorecard will cascade to regional and country levels for presentation at appropriate regional and country events.

The Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa is an alliance to bring a Green Revolution to Africa. With roots in farming communities, the Alliance emphasizes transitioning African agriculture from a collection of primarily solitary, subsistence farms providing food for the household to farms as businesses and income opportunities including for smallholders. The African Green Revolution Forum meets annually, and in even years attracts high-level decision makers to help discern and commit to specific actions to accelerate African agricultural growth. The African Agricultural Status Report is typically launched at these Forums.

Most recently, Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta hosted the Agricultural Green Revolution Forum—Nairobi, Kenya: Sept. 5-9, 2016—that attracted over 1500 delegates from 40 countries representing African governments, donors, the private sector and civil society under the theme “Seize the Moment: Securing Africa’s Rise through Agricultural Transformation”. Highlights include refreshed country pledges to allocate 10% of national budgets to agriculture supported by spending plans to achieve this target, to bring $20 billion of private investment into agriculture, to remove the five biggest regulatory and policy bottlenecks holding back agricultural investment and agriculture, and to strengthen accountability processes.

In 2011 the African Union, NEPAD and the World Economic Forum founded the Grow Africa Partnership to facilitate private-sector investment in agriculture by facilitating collaboration among the private sector, governments, and smallholder farmers. The overall objective is to reduce hunger and poverty through agricultural growth. The Grow Africa Partnership is active in 12 countries and has over 200 corporate members. The Grow Africa Partnership secretariat recently relocated from Geneva to the NEPAD headquarters in South Africa.

The Grow Africa Investment Forum is an annual event designed to highlight private sector investment opportunities, disseminate information on best practices, and promote dialog on additional actions to stimulate inclusive agricultural growth. Rwanda hosted the May 10-11 2016 Forum with attendance of about 250 people. This event can provide networking opportunities for the private sector.

Africa’s Regional Strategic Analysis and Knowledge Support System hosts an annual conference centered on the release of the Annual Trends and Outlook Report. This report summarizes the CAADP indicators of agricultural sector performance, and puts them in historical context. Each conference and report also focuses on a specific theme related to agricultural transformation: at the last conference—October 2016; Accra, Ghana—the theme was nutrition transition.

In 2012 the Group of Seven leading world economies in cooperation with the African Union helped initiate the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition. With ten African countries as partners, the New Alliance helps elevate attention to public investment and policy change necessary to increase responsible private sector investment in agriculture. Each country has developed a cooperation framework, which specifies donor funding commitments, government policy commitments, and private sector investment intentions within the country.

CAADP has a complex partnership structure; the most accessible entry point is the annual partnership platform meeting. The overall partnership structure is designed to facilitate and coordinate CAADP implementation. This annual partnership platform meeting is focused both on CAADP implementation in general and also on annual theme calling attention to a specific agricultural development issue relevant to CAADP, for example, in 2016 the theme was innovative financing. This meeting generates some progress at a continental level towards the mutual accountability components of identifying priority goals, actions, and targets, and creating an inclusive dialog around what government commitments are most useful to help achieve these targets. The meeting is typically widely attended with representatives from government, donors, NGOs, farmers’ organizations, and the private sector. It can be a very useful networking opportunity.

African agriculture is changing rapidly, and so are the opportunities for profitable private-sector investment. However, three big obstacles to African agricultural investment remain. First, government provision of agricultural public goods such as water, power and transportation infrastructure is inadequate. Despite African presidential commitments in 2003 to allocate 10% of budgets to agriculture, few countries have achieved this target. Second, outdated sector policies and policy processes inhibit private sector investment. For example, most African countries rank very low on metrics such as the Doing Business Index and the Enabling the Business of Agriculture Index. Third, mistrust between government, the private sector, and civil society raises transactions costs and alters the risk-reward profiles of potential investments. These three obstacles mean that similar investment opportunities may have different risk-reward profiles in different countries based not just on the general agricultural policies and public investment, but also on the specific socio-political context of the specific investment. This raises the difficulty for the private sector to invest widely, and the difficulty of coordinating public and private stakeholders to drive the sector and the food system forward. Newly established mutual accountability processes have the potential to overcome all three of these obstacles.

A key change over the past two years is the elevated attention to mutual accountability including the African Heads of State commitment to mutual accountability in Malabo. Mutual accountability processes themselves provide a critical entry point for the private sector, particularly with respect to dialog with government and other stakeholders about what policy systems can best enable private investment to accelerate inclusive agricultural growth. Companies that are looking for new opportunities may find this an opportune time to investigate the potential of African agricultural investment.

African Union. 2016. “African Union: Rural Economy and Agriculture.” Available online: http://www.au.int/en/rea

African Union. 2014. “Malabo Declaration on Accelerated Agricultural Growth and Transformation for Shared Prosperity and Improved Livelihoods.” Available online: http://pages.au.int/sites/default/files/Malabo%20Declaration%202014_11%2026-.pdf

Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA). 2016. “AGRA: Growing Africa’s Agriculture.” Available online: https://agra.org

Covic N. and S. Hendricks. 2016. “Achieving a Nutrition Revolution for Africa: The Road to Healthier Diets and Optimal Nutrition.” ReSAKSS: Annual Trends and Outlook Report 2015 Washington, D.C.: International Food Policy Research Institute. Available online: http://www.resakss.org

Dorosh P and Thurlow J. 2014. Beyond Agriculture versus Nonagriculture: Decomposing Sectoral Growth–Poverty Linkages in Five African Countries. International Food Policy Resarch Institute IFPRI Discussion Paper 01391. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2539591

Grow Africa Partnership. 2016. “Grow Africa.” Available online: http://www.growafrica.com

Hendrix, C. and H.J. Brinkman. 2013. “Food Insecurity and Conflict Dynamics: Causal Linkages and Complex Feedbacks.” Stability: International Journal of Security and Development. 2(2), p.Art. 26. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/sta.bm

Krieger, T. and D. Meierrieks. 2016. Does Income Inequality Lead to Terrorism? CESifo Working Paper Series No. 5821. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2766910

Lowder S.K., J. Skoet, and T. Raney. 2016. “The Number, Size, and Distribution of Farms, Smallholder Farms, and Family Farms Worldwide.” World Development, 87(Nov):16-29. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.10.041.

New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition. “New Alliance: For Food Security and Nutrition.” Available online: https://new-alliance.org

New Partnership for Africa’s Development. Available online: http://www.nepad.org

New Partnership for Africa’s Development. “Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP).” Available online: http://www.nepad-caadp.net

New Partnership for Africa’s Development. 2014. “Implementation Strategy and Roadmap to Achieve the 2025 Vision on CAADP: Operationalizing the 2014 Malabo Declaration on Accelerated Agricultural Growth and Transformation for Shared Prosperity and Improved Livelihoods.” Available online: http://www.nepad.org/system/files/Implementation%20Strategy%20Report%20English.pdf

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2011. “The Busan Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation.” Available online: http://www.oecd.org/development/effectiveness/busanpartnership.htm1.

Regional Strategic Analysis and Knowledge Support System (ReSAKSS). Available online: http://www.resakss.org

World Bank. 2016a. “World DataBank: Health, Nutrition and Population Statistics.” Available online: http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=health-nutrition-and-population-statistics#

World Bank. 2016b. “World DataBank: World Development Indicators.” Available online: http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=world-development-indicators