Thriving places are often recognized as those where it is desirable to live, work, start a business, or raise a family. Measuring this sort of well-being, however, has been a persistent and urgent challenge for researchers, practitioners, and elected officials. Behind this challenge is the complication of the sheer diversity of places and the people who live in those places. Distinct histories, economies, and communities make it nearly impossible to assign a nationally comparable set of the indicators of place prosperity. This is no less true for rural places, which exist as “a mosaic of different landscapes, people, and economic realities” (Kerlin et al., 2022, p. 2). Despite this limitation within the research, as noted by Lichter and Johnson (2022), there is a widely held belief that rural America is being left behind. While Lichter and Johnson, among others (Deller and Conroy 2022), challenge this perspective, empirical studies presenting an alternative picture to one of stagnation and decline in rural America are few and far between.

One driver of the pervasive narrative of declining rural places is the emphasis on economic growth. Indeed, to overcome the challenge of heterogeneity across places, researchers often narrow their analyses to well-established—and nationally comparable—economic growth measures. Although economic growth is often an objective of rural places, by itself, economic growth does not fully encompass what it means for a place to be doing well. That is, to oversimplify community economic development into “jobs, jobs, jobs” is to ignore that the features of a good quality of life extend well beyond the economy.

The typical measures of well-being that focus exclusively on economic growth inadequately capture the noneconomic factors that communities increasingly recognize as essential to well-being. Even more, focusing on growth can be misleading: Just because a place is growing economically does not necessarily mean it is a good place to live. Perhaps more importantly, just because a place is not growing does notmean it is an undesirable place to live. Many communities with high quality of life can appear stagnant using traditional measures of growth. This observation is particularly true for many rural communities which seek prosperity without losing the “ruralness” that is often lost to growth processes. Indeed, as noted by Lichter and Johnson (2022) and Deller and Conroy (2022), many growing rural communities find themselves reclassified from rural (or nonmetropolitan) to urban (or metropolitan), and this reclassification leads to distortions in our understanding of rural America.

While research on understanding the creation of economic opportunities is well established, the research on community level quality of life (also referred to as well-being or prosperity) is less well understood (Dsouza, et al. 2023; Veréb, et al. 2024). One way research can contribute to broader policy discussions at the national, state, and local levels is by generating measures that quantify local prosperity and interpreting broad prosperity trends. Such applied research can allow for finer insights into policy options. In this study, we expand on one well-received way of measuring place prosperity that departs from a growth paradigm, introduced by Isserman, Feser, and Warren (2009). We extend this measure across time for all U.S. counties to analyze change in prosperity, as distinct from growth, and create a new typology of prosperity. Ultimately, we identify three elements of prosperity critical for both future research and policy intervention: 1) prosperity is a transitory state that can change over time; 2) prosperity varies regionally across the United States; and 3) there are distinct patterns of prosperity across the urban–rural continuum. These findings contribute to a more nuanced understanding of local prosperity on the national scale and encourage reorienting the study of community prosperity on change over time, both of which are critical for the principal aim of improving the well-being of places.

Growth-centric measures of community well-being tend to emphasize jobs, income, and population. Using economic growth as a proxy for well-being is convenient but limiting—often painting a misleading picture of rural places in at least three ways. First, as noted above, rural places that are doing well from a purely growth perspective are often reclassified as urban places, which can mark rural places as perpetually left behind by growth standards. Second, rural places that are not growing, but are seen by-and-large as decent places to live, can be obscured by growth metrics. Third, because economic “success” is often equated with growth, rural communities that focus on well-being and quality of life rather than more traditional notions of growth are often viewed as lagging behind or stagnant despite their explicit goal of retaining their rural characteristics.

In response to this line of critique, Isserman, Feser, and Warren (2009) offered a new Prosperity Index (PI) to measure place well-being. They sought to develop a simple measure of prosperity that did not rely solely on indicators of economic growth, which tend to favor urbanizing places. Instead, they aimed to depict a wider characterization of place well-being beyond growth. Their PI compares county rates of 1) poverty, 2) unemployment, 3) high school dropouts, and 4) substandard housing to the national average for the year 2000. To calculate the PI, each county receives a point for every one of the four dimensions that they score better than the national average. The PI is the sum of these four dimensions, producing a composite score ranging from 0 to 4 for every county in the United States. Here lower values of the PI are associated with lower levels of prosperity and higher values are associated with higher prosperity.

We build on the PI by extending it over time, from 1990 to 2022 across four intercensal periods using sequence analysis, a methodological approach used to study sequences of social behaviors, events, or processes (Losacker and Kuebart, 2024). Sequence analysis has been used in sociology to understand life-course transitions (for example, marriage, education, employment), communication studies to examine sequences of online interactions or conversation dynamics, demography to study family formation and dissolution patterns, and criminology to better understand patterns of criminal behavior over time, among other fields of study (Golyandina, Nekrutkin, and Zhigljavsky 2001).

In this study, we use sequence analysis to identify changes in prosperity scores and string scores together to generate what we call “Prosperity Pathways.” For example, if a county has a score of 4 in 1990, 3 in 2000, 2 in 2010, and 1 in 2020, the county’s Prosperity Pathway would be 4-3-2-1. This hypothetical county exhibits patterns of declining levels of prosperity over time, as compared to the national average. Connecting a county’s prosperity scores together into interpretable sequences facilitates our ability to illustrate and analyze patterns over time.

We identify more than 300 unique Prosperity Pathways over the study period. This means there are hundreds of ways prosperity changes, implying that there is significant heterogeneity across U.S. communities (proxied in this empirical analysis by counties). The direct policy implication is that such heterogeneity requires a bottom-up approach to community economic development policies: One-size-fits-all approaches to community economic development policy making do not work. Prosperity Pathways can offer key insights into how prosperity changes across time and space.

Analyzing prosperity over time reveals the trend or direction of change for each U.S. county. That is, we can identify which places are consistently prosperous or “lacking” prosperity, as well as where places are becoming more or less prosperous. Identifying how prosperity changes over time can give important insights into how community economic development initiatives are shaping the well-being of places. These insights are of particular interest to researchers, community economic development practitioners, and elected policy makers who want to understand prosperity to change it—to improve the well-being of the places and communities where they live and work.

Identifying the pathway a place takes to and from prosperity can give important insights into how community economic development initiatives are shaping the well-being of places. We find that prosperity exhibits a variety of directional changes over the study period, including Prosperity Pathways that are consistently increasing or decreasing, fluctuating, or stable.

We find a roughly even split between counties that have experienced change in prosperity and counties with stable prosperity scores over the study period. Just under half of all counties (49%) are stable, with prosperity scores changing little over the last 30 years. In fact, roughly 13% of all U.S. counties do not change prosperity score over the study period. “Stable” counties range from the most prosperous to the least prosperous counties and exist across the urban–rural continuum. While characterized by stability in the most recent time period, these counties may have experienced significant change prior to the start of the study period (1990).

The remaining counties experience significant change in prosperity. Of these, 11% of counties exhibit patterns of continuous prosperity improvement, while less than 5% of counties are in consistent prosperity decline over the study period—perhaps a much smaller share than narratives of rural decline would suggest. For 35% of counties, Prosperity Pathways follow no clear trend, fluctuating (sometimes dramatically) between states of prosperity. Some counties experience improvement and then decline or decline and then improvement. Others oscillate or experience a “shock,” where prosperity changes a great deal before reverting to normal levels. A simple plotting of the Prosperity Pathways (Figure 1) reveals large swaths of counties in the Southeast and Appalachia, as well as parts of the Plains and Southwest, are witnessing prosperity improvement over time. Some counties in the Great Lakes region, Florida, and New England are declining.

That prosperity can, and does, change over time is an encouraging finding for community economic development. Place well-being is not a static fact but rather a process that is subject to change; however, why, where, and how prosperity changes—or does not—remains an open question.

This means that places with high prosperity tend to besurrounded by other places with high prosperity, and places with low prosperity are surrounded by other places with low prosperity.

As another way to evaluate community well-being, we categorize counties into five groups based on similar Index scores over time, ranging from “Extremely Prosperous” to “Lacking Measurable Prosperity.” Extremely Prosperous counties routinely score above the national average for all or most prosperity dimensions over the study period. Counties classified as “Lacking Measurable Prosperity” most often do not meet or exceed the national average for the dimensions of prosperity that we measure.

Mapping Prosperity Pathways in this way reveals important regional trends of community well-being (Figure 2), including most notably, a high clustering effect of community prosperity. That is, while change in prosperity is spread relatively evenly across the United States (Figure 1), average prosperity scores over time are geographically clustered. Spatial clustering effects are common across other measures of well-being, but because the Prosperity Pathways approach does not rely solely on growth or amenity indicators, the resulting depiction of prosperity offers a unique perspective. This alternative depiction of the spatial distribution of prosperity is especially prominent in rural areas and places that may otherwise be considered as “left behind" using more typical growth metrics. For example, by our measure, many “Extremely Prosperous” counties that exceed the national average across multiple or all indicators are concentrated in the region historically associated with the Rust Belt as well as through the northern portions of the Great Plains. At the same time,

some geographic clusters of less prosperous counties are more aligned with the spatial distribution of typical growth-focused measures of prosperity. These clusters are primarily in the South, including parts of eastern Kentucky, parts of West Virginia, and much of western Tennessee; some of the Southwest, including much of New Mexico and eastern Arizona; and a broad swath of the Pacific coast. There are also smaller pockets of less prosperous counties, such as in the southern tip of Texas, parts of southern Florida, and parts of northeastern Michigan.

While a clustering effect of prosperity scoring is prominent, it is not universal. There are instances of counties with differing prosperity clustering together. For example, a common pattern in the Upper Midwest is prosperous suburban counties surrounding a less prosperous urban core, such as Chicago (Cook County, Illinois) or Milwaukee (Milwaukee County, Wisconsin). This finding, when combined with the geographic spread of prosperity change, reinforces that geography is not an insurmountable limitation of improving prosperity. While geography is important for prosperity, it is not the only factor.

Third, prosperity exists across the urban–rural continuum. Both rural and urban counties exhibit all levels of prosperity, and all types of prosperity change. The particularities of a place matter a great deal for how prosperity is locally understood. Indeed, this is one of the primary challenges of measuring place well-being. What it means for an agricultural community to be “doing well”will not be the same as for a college town or major city. Place well-being across the urban–rural continuum is one example of how important it is to have measures of well-being that are flexible enough to account for place individuality.

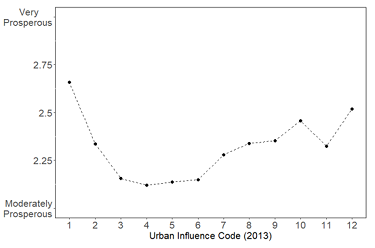

To measure place prosperity across the urban–rural continuum, we use two different classifications of the urban–rural spectrum. The first groups counties into one of three classifications: metropolitan, nonmetropolitan that are adjacent to a metropolitan county, and nonmetropolitan that are not adjacent to a metropolitan county. The second uses the USDA Economic Research Service Urban Influence Codes (UICs), which sorts counties into 12 degrees of rurality/urbanity with 1 being the “most urban” and 12 being the “most rural.” UICs are determined based on the Office of Management and Budget’s metropolitan, micropolitan, and noncore county groupings. While UICs are widely accepted as a reasonable reflection of the urban–rural spectrum, it falls short of a perfect urban-to-rural spectrum for a variety of reasons from the coarse scale, focus on population metrics, and oversimplification of complex geographic, social, and economic realities. For example, a county with a very small population base that is adjacent to a metropolitan county is viewed as more urban than a county with a similar population that is not adjacent.

When considering how rural and urban places have changed in prosperity over time, we find that rural counties are more likely to be increasing in prosperity than urban counties (Table 1). More than 12% of nonmetro adjacent counties and 15% of nonmetro remote counties are increasing in prosperity scores, whereas 7% of metro counties are increasing. When looking at counties with decreasing prosperity the pattern reverses. Just 4% of nonmetro adjacent and 3% of nonmetro remote are decreasing, whereas 6% of urban counties are decreasing. While many measures of place well-being that are confined to economic growth indicators depict rural places as falling behind, our measure shows rural places as improving on dimensions that extend beyond economic growth.

Further, despite the uniqueness of individual places, it is clear from our findings that prosperity is not exclusive to urban or urbanizing places. In fact, we find the most rural counties nearly match the most urban places with the highest average prosperity scores over time (Figure 3). The “least” prosperous counties over time are those with sizable populations (2,500 to 20,000+), adjacent to metro counties.

When place well-being is measured beyond one-dimensional growth indicators, rural counties are extremely competitive with their more urban counterparts in demonstrating themselves as good places to live. This result is particularly important as it challenges the widely held perspective that rural America is lagging behind. When we expand our notions of community economic development beyond simple notions of economic growth and think in terms of prosperity or well-being, a very different picture of many parts of rural America becomes clear.

Indeed, some of the most rural places in the United States are quite prosperous. For example, rural Ness County in western Kansas has unwaveringly ranked at the top of the PI for the study period, as have 23 other remote counties with fewer than 5,000 residents.Likewise, rural counties, by our measure, are improving prosperity. One example is Luce County: The second most rural county in Michigan, Luce County is the only county in the Upper Peninsula that experienced a consistent increase in prosperity score over the study period. Thus, to write off rural places as “left behind,” in decline, or otherwise less than is misleading and can result in poorly designed policy.

Deller, S.C., and T. Conroy. 2022. “Regional Economic Trends Across the Rural-Urban Divide.” In N. Walzer and C. Merrett, eds. Rural Areas in Transition. Routledge, pp. 19–44.

Dsouza, N., A. Carroll-Scott, U. Bilal, I.E. Headen, R. Reis, and A.P. Martinez-Donate. 2023. “Investigating the Measurement Properties of Livability: A Scoping Review.” Cities and Health 7(5):839–853.

Golyandina, N., V. Nekrutkin, and A.A. Zhigljavsky. 2001. Analysis of Time Series Structure: SSA and Related Techniques. CRC Press.

Isserman, A.M., E. Feser, and D.E. Warren. 2009. “Why Some Rural Places Prosper and Others Do Not.” International Regional Science Review 32(3):300–342.

Kerlin, M., N. O’Farrell, R. Riley, and R. Schaff. 2022. “Rural Rising: Economic Development Strategies for America’s Heartland.” Public Sector Insights. McKinsey and Company.

Khatiwada, L.K. 2014. “Modeling and Explaining County-Level Prosperity in the U.S.” Journal of Regional Analysis and Policy 44(2):143–156.

Lichter, D.T., and K.M. Johnson. 2022. “Urbanization and the Paradox of Rural Population Decline: Racial and Regional Variation.” Socius 9:1–21.

Losacker, S., and A. Kuebart. “Introducing Sequence Analysis to Economic Geography.” Progress in Economic Geography 2(1):100012.

Rahe, M.L. 2009. “Rural Eutopia: Can We Learn from Persistently Prosperous Places?” PhD Dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Schmidt, D., T. Conroy, S. Deller. 2024. “Prosperity Across the United States: Revisiting the Isserman, Feser, and Warren Prosperity Index Using Social Sequence Analysis.” Working paper.

Veréb, V., C. Marques, L. Madureira, C. Marques, T. Keryan, and R. Silva. 2024. “What Is Rural Well‐Being and How Is It Measured? An Attempt to Order Chaos.” Rural Sociology 89(2):239–280.

Wilson, B., and M.L. Rahe. 2016. “Rural Prosperity and Federal Expenditures, 2000–2010.” Regional Science Policy and Practice 8(1–2):3–26.