Immigration has been a central issue in U.S. national elections in recent years. During his campaign, President Trump made reducing undocumented immigration and reforming legal immigration rules a top priority. To achieve the first goal, the new administration promised to conduct mass deportations, targeting not only individuals with criminal records but any person living in the United States illegally. This approach could have significant economic consequences for industries that have long depended on undocumented immigrants, like agriculture. Along with employers in construction and hospitality (restaurants and hotels), farmers in America have been dealing with labor shortages for many decades (Gutiérrez-Li, 2024a; Hertz and Zahniser, 2013). A significant reduction in the supply of workers could exacerbate existing challenges and have broad economic impacts.

To achieve his immigration goals, the president signed several executive orders upon taking office (Bustillo, 2025). The policies outlined in Table 1 could reduce the labor supply in sectors that have historically relied on undocumented workers. First, if individuals already working in the U.S. are deported, there would be a direct reduction in the availability of workers. Second, other undocumented workers who are not deported or caught could decide to self-deport or reduce their number of working hours (partially or totally) to minimize the probability of apprehension. In such case, there would be an added “chilling” effect on labor supply. Third, some of the proposed policies (like expanding the border wall and adding other physical barriers), and deterrence efforts would likely result in a reduction of further immigrant arrivals. Moreover, the decision to end measures from the previous administration like granting temporary legal status to some individuals would result in a decline of (legal) workers. In sum, the policies listed in Table 1 could lead to both a reduction in the stock and flow of immigrants, which could further exacerbate labor shortages in the sectors that have struggled to recruit domestic workers and are far from automating production processes.

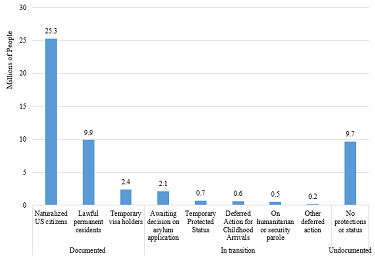

The policies in Table 1 are all meant to reduce the size of the undocumented population in the United States. While estimates vary, recent studies suggest that more than 13 million individuals currently live in the United States illegally (Van Hook, 2025). As seen in Figure 1, there were approximately 51.4 million foreign-born individuals in the United States in 2023. Of those, 37.6 million were fully documented (naturalized citizens, green card holders, and temporary visa holders) and 3.9 million had some type of permission to stay in the country but temporarily and could potentially be deported shortly (e.g., people under temporary protected status like Haitians or individuals awaiting asylum decisions). Many individuals in the second group likely entered the country illegally. Finally, 9.7 million people did not have any sort of permission to be in the country (i.e., were undocumented) and had no recourse to prevent their immediate deportation. Generally, only citizens cannot be deported, as residents and visa holders can lose their legal status under certain conditions (like committing crimes or providing fraudulent information).

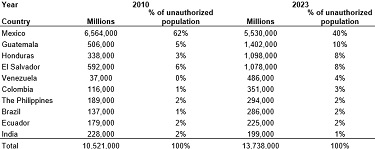

According to Van Hook (2025), the number of undocumented immigrants started rising in 2020, mostly due to the large number of individuals that entered the country illegally during and after the pandemic. While the population of undocumented immigrants has been above 10 million since 2010, political turmoil in countries like Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Haiti likely explains the significant inflow of individuals through the southern border (as well as the granting of temporary legal status to individuals from these countries by the previous administration).

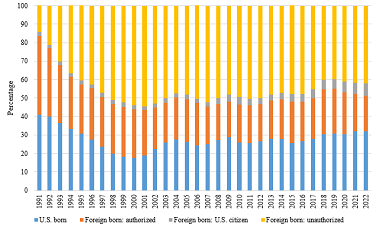

Many undocumented individuals that entered decades ago have remained in the country and are integrated with local communities in different ways, particularly as workers. Since the size of this group has been at least 10 million people for more than a decade (Van Hook, 2025), industries that employ such workers have become de facto reliant on this labor force. In the case of agriculture, official data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture shows that, in the last 3 decades, at least 40% of the crop labor force has been undocumented (Figure 3). Industries like dairy (which, in essence, does not have access to H-2A workers due to the program’s regulations),[1] meatpacking and poultry plants, and nurseries and greenhouses producing indoor and other ornamental plants also depend on undocumented workers. Other sectors where undocumented immigrants are vastly over represented are construction, restaurants and hospitality, housekeeping and cleaning services, grounds maintenance, carpentry, painting, roofers, and hand packaging (East, 2024). All these industries are heavily reliant on manual labor, mostly without college degrees, and are key to economic growth.

Considering the rise in the number of undocumented workers in recent years, and the historical presence of these workers in agricultural operations, it bears to ask if there has been an increase in the agricultural labor supply. Although there is no official information on whether the new arrivals are employed and, if so, in which industries, there is little evidence that new undocumented immigrants are working in agriculture. Most farm workers in the United States (documented or not) are young men from Mexico with lower levels of schooling. As shown in Table 2, Mexicans represented 62% of the undocumented population back in 2010, but the share declined to 40% in 2023. Undocumented immigrants that came after the pandemic originate predominantly from countries like Venezuela, Ukraine, Nicaragua, and Haiti, among others (Van Hook, 2025). People from these nationalities have not traditionally worked on U.S. farms, and most H-2A workers come from Mexico (Gutiérrez-Li, 2024a). For instance, Venezuelans are more likely to have a college degree and live in larger metro areas (Hoffman and Batalova, 2023), increasing their odds of working outside the farm sector.

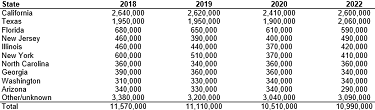

Given that recent immigrants to the United States are not likely working in agriculture, ending temporary permits (like TPS, temporary protected status) is not likely to affect the farm labor supply significantly. However, if mass deportations are carried out, many undocumented individuals from Mexico who have been working on farms for many years could be removed. If this happens, the agricultural labor supply will be drastically reduced. Data from the Department of Homeland Security shows that most undocumented individuals reside in California, Florida, North Carolina, Washington, and Georgia (Table 3). Coincidentally, those states are in the top 5 based on demand for H-2A workers, an indicator of the importance of labor-intensive agricultural operations (Gutiérrez-Li, 2021). Agricultural production in those states includes fresh fruits, vegetables, other specialty crops, and nurseries and Christmas trees, among others. Hence, mass deportations could hit these areas of the country particularly hard, as these agricultural operations are not vastly mechanized, unlike in other areas of the country like the Midwest, where automated row crop production dominates.

Employers in key industries in America have struggled to recruit and retain workers for many years (Gutiérrez-Li, 2024a). Immigration policies designed to shrink the sizeof the undocumented labor force—a group that has historically been overrepresented in sectors like agriculture, construction, hotels and restaurants—could likely worsen the challenges.

The top goal of the new administration is to strengthenimmigration enforcement, both at the border and the interior. The former can reduce the number of new workers entering the United States, while the latter could shrink the existing labor force if individuals who have been working on farms and other industries are deported. Immigration enforcement could reduce the overall labor supply by decreasing the number of workers directly (the ones deported) and indirectly, as other workers may decide to work fewer hours in fear of being deported, a phenomenon known as chilling effects (East et al., 2023). In addition, mass deportations could include immigrant entrepreneurs, whose importance to the American economy has grown over time (Gutiérrez-Li, 2024b).

A significant reduction in the farm labor supply would have negative consequences for workers, who would lose their main income source. Likewise, employers would see their main revenue source curtailed, as there have been cases in the past of food rotting in the fields due to labor shortages and housing costs going up. Importantly, the effects could be felt by all Americans.The economies of rural communities where labor-intensive agriculture dominates could be hurt, the new supply of housing could slow down, and hotels and restaurants could hike prices if staffing shortages become more prevalent. In the case of agriculture, a sharp decline in the number of undocumented farmworkers could be countered with a faster increase in the number of H-2A workers. However, this would requireupdating the H-2A program, which is costly, bureaucratic, and leaves out nonseasonal sectors like dairy. Past efforts to achieve such goals, introduced in the different versions of the Farm Work Force Modernization Act, have repeatedly failed in Congress.

Since attracting domestic workers to agricultural jobs has proven unrealistic even during periods of high unemployment (Luckstead, Nayga, and Snell, 2022), the only viable alternative is automating production processes. Mechanization is likely to help, but only in the long run, as the technologies currently available are not as efficient and are financially prohibitive to many producers (Gutiérrez-Li, Escalante, and Acharya, 2024).

Given that consumer demand for fresh products is not expected to wane any time soon, if labor costs rise sharply due to exacerbated shortages, either households will have to pay more for American-grown food or we might see a rise in imports of fruits and vegetables from other countries. Combined, mass deportations affecting multiple industries could fuel inflationary pressures and reduce GDP (gross domestic product), impacting the entire economy.

Baker, B., and R. Warren. 2024. Population Estimates: Estimates of the Unauthorized Immigrant Population Residing in the United States: January 2018–January 2022. U.S. Department of Homeland Security Office of Homeland Security Statistics. Available online: https://ohss.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/2024-06/2024_0418_ohss_estimates-of-the-unauthorized-immigrant-population-residing-in-the-united-states-january-2018–january-2022.pdf

Bustillo, X. 2025, January 20. “Trump Signs Sweeping Actions on Immigration and Border Security on Day 1.” NPR Politics. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2025/01/20/g-s1-43650/trump-inauguration-day-one-immigration

East, C. 2024. September 18. “The Labor Market Impact of Deportations.” Brookings Institute. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-labor-market-impact-of-deportations/

East, C.N., A.L. Hines, P. Luck, H. Mansour, and A. Velasquez. 2023. “The Labor Market Effects of Immigration Enforcement.” Journal of Labor Economics 41(4):957–996. https://doi.org/10.1086/721152

Gutiérrez-Li, A. 2021. “The H-2A Visa Program: Addressing Farm Labor Scarcity in North Carolina.” NC State Economist. North Carolina State University. Available online: https://cals.ncsu.edu/agricultural-and-resource-economics/wp-content/uploads/sites/46/2024/07/NC-State-Economist-Summer-2021.pdf

———. 2024a. Feeding America: The Role of Immigrants in the U.S. Agricultural Sector. Rice University Baker Institute for Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.25613/Z5BY-GZ22

———. 2024b. “Home Country Work Experience and Immigrant Self-Employment in the United States.” International Migration Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/01979183241262966

Gutiérrez-Li, A., C. Escalante, and S. Acharya. 2024, April 17. “The Costs and Benefits of Mechanization: A Look at the Dairy Sector.” Southern Ag Today 4(16.3).

Hertz, T., and S. Zahniser. 2013. “Is There a Farm Labor Shortage?” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 95(2):476–481. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aas090

Hoffman, A., and J. Batalova. 2023, February 15. “Venezuelan Immigrants in the United States.” Migration Information Source. Migration Policy Institute. Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/venezuelan-immigrants-united-states-2021

Luckstead, J., R.M. Nayga, Jr., and H. Snell. 2022. “U.S. Workers’ Willingness to Accept Meatpacking Jobs amid the Covid-19 Pandemic.” Journal of the Agricultural and Applied Economics Association 1(1):47–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaa2.8

U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service (USDA-ERS). 2025. Farm Labor. Available online: https://usda.library.cornell.edu/concern/publications/x920fw89s [Accessed April 2025]

Van Hook, J. 2025, February 4. “Who Are Immigrants to the US, Where Do They Come from and Where Do They Live?” The Conversation. Available online: https://theconversation.com/who-are-immigrants-to-the-us-where-do-they-come-from-and-where-do-they-live-247430