Since the 2011 Choices theme on beginning farmers and ranchers (Thilmany McFadden and Sureshwaran, 2011), both societal interest and government support for new farmers and ranchers have grown considerably. Many agencies within the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) including the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) increased their emphasis on new farmers as a result of the 2014 Agriculture Act, or “farm bill” (Williamson, 2014), and the USDA has integrated information and support from across the Department in a coordinated effort that includes a comprehensive web resource encouraging new farmers to use the full range of USDA programs, whether specifically targeted at beginners or not (USDA, 2016). Most USDA programs consider a new or beginning farmer to be someone who has been operating a farm or ranch less than ten years, or someone who aspires to enter farming or ranching.

Since 2009, the Beginning Farmer and Rancher Development Program (BFRDP), run by NIFA, provides grants to organizations for education, mentoring, and technical assistance initiatives for beginning farmers or ranchers. Its primary goal is to increase the number, success and sustainability of beginning farmers and ranchers in the United States by providing them knowledge, skills, and tools needed to make informed decisions. This goal is achieved through competitive grants to collaborative State, tribal, local, or regionally-based networks or partnerships of public or private entities, who carry out three kinds of projects: standard grants, educational enhancement teams, and a national clearinghouse.

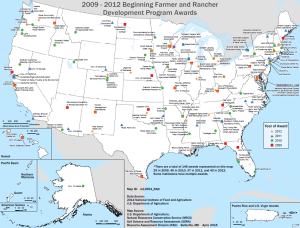

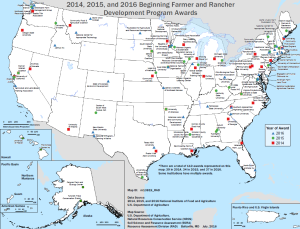

Since its inception in 2009, BFRDP has made 256 awards totaling more than $126 million, at least one in every state (Figures 1 and 2). Current funding is $20 million per year (less “sequestration”) for the years 2014-2018, provided in the 2014 Agriculture Act.

Standard grants address the unique training, education, outreach, and technical assistance needs of beginning farmers and ranchers in a particular local or regional setting. They offer workshops and hands-on experience in the full range of topics needed by aspiring and new farmers: farming and ranching methods, marketing strategies, natural resource conservation strategies, financial and business planning, management, and more. Since most are three-year projects, those funded in 2009-2012 have been completed, whereas most projects funded in 2014-2016 are still underway. Funded projects use a wide variety of educational and technical assistance methods. Some offer workshops, demonstrations, and classes across a state or a multi-state region. Such projects often have several tracks for people at different stages in their exploration of farming and ranching, such as an introductory seminar for “explorers,” a more in-depth workshop or course for more serious students, and a season- or year-long series of workshops for the most committed. Hands-on experiences and interactions with practicing farmers are nearly always involved, often supplemented by on-line training or tools. By contrast with statewide or multi-state projects, some projects are highly localized, offering more intensive experiences such as apprenticeships, mentoring, or the opportunity to farm for a few years in a protected setting, commonly referred to as an “incubator farm”.

Educational Enhancement Team projects do not serve farmers directly. Rather, they “train the trainers” and help enhance other beginning farmer and rancher education programs in the nation. Typically, they focus on a particular audience, region or topic, for which the team reviews beginning farmer and rancher curricula and programs, identifies gaps, and develops and disseminates materials and tools to address the gaps. (Box 1).

Seven BFRDP Educational Enhancement Team (EET) projects are currently active, funded in 2014-2016. One concerns a key topic (land access), two address specific audiences (women and immigrants), and two involve educational methodologies (apprenticeships and the farmer-led Farm Beginnings curriculum). Two more EETS were funded in 2016 to work with NIFA on two program priorities: evaluating completed projects, and assisting less experienced applicants.

The seven current EET projects are:

Five additional, completed team projects, funded in 2009-2012, supported two collaborative networks—the Farm Beginnings Collaborative and a training network among organizations in the Northeastern United States.—and projects on financial management, asset building, and livestock environmental stewardship (USDA-NIFA, 2013).

BFRDP also funds a national clearinghouse that provides information to new farmers and support to those who work with them. The first national clearinghouse, operated by the National Agricultural Library and its partners, developed Start2Farm.gov, which has since been incorporated into the main USDA web site for new farmers. In 2014, BFRDP re-competed the clearinghouse award, with a new result. The Farm Answers (FarmAnswers.org) digital library of publications, videos, presentations, apps, and on-line courses, provides the nation’s largest source of information for beginning farmers and those who work with them—over 4,000 items and growing. They are organized by topic (multiple topics under the main headings of business management, marketing, people, production, and taxes & legal); format (written material, video, audio, presentation, online course, app, or website), production/marketing system (including local, organic, or urban), commodity type, and location (national, regional, or state).

Figuring out where to start with such a large collection can be daunting, so Farm Answers has a “toolbox” section that features ten or so top-level items on each of a number of high-priority topics, such as business planning, financial management, direct marketing, commodity marketing, organic agriculture, urban agriculture, farmland access, farm transition planning, and food safety.

Farm Answers also houses information on hundreds of new farmer programs nationwide, plus blogs and news feeds, social media, and much more. It is operated by the University of Minnesota’s Center for Farm Financial Management, in partnership with USDA-NIFA and the other BFRDP funded projects.

BFRDP serves new farmers and ranchers of all types – small, mid-size, and large; organic and conventional; commodity producers and specialty crop growers; young people and second-career farmers. Applicants to BFRDP are required to describe their target audience and their needs, and explain how the proposed project will address their specific needs. While some projects focus on a particular topic, most cover a range of topics in production, marketing, and business management, since most new farmers have needs in all of those areas.

In addition, there are two audiences specified by Congress for particular attention. By law, at least 5% of BFRDP funds must go to projects serving military veteran beginning farmers and ranchers, and at least 5% of BFRDP funds must go to projects serving socially-disadvantaged, limited-resource, or farmworker beginning farmers and ranchers. NIFA has met or exceeded these amounts in each year of the program (Table 1).

The focus on socially-disadvantaged, limited-resource, and farmworker audiences began in 2009, and the requirement to allocate funding to projects serving them was at a higher level (at least 25% of funding) from 2009 to 2012 (Farm Security and Rural Investment Act of 2002). Socially-disadvantaged groups are defined as those whose members have been subjected to racial, ethnic, or gender prejudice because of their identity as members of a group without regard to their individual qualities (Consolidated Farm and Rural Development Act of 2003). In the Agricultural Act of 2014, the requirement was reduced to 5%, but the applications received and those awarded funding continue to exceed the earlier requirement (Agricultural Act of 2014). More than half of the funded projects serve one or more socially-disadvantaged audiences with a portion of their effort and funding. Some projects concentrate their efforts on a single audience of interest, but in some others, two or more groups, each with expertise and contacts in a particular culture or community, collaborate successfully (Box 2).

Two intertwined projects and organizations in Minnesota demonstrate how the BFRDP program has both served socially-disadvantaged, limited-resource populations, and has built the capacity of immigrant and ethnic minority run organizations to provide services. These projects are staffed by and deliver services to Hmong and Latino farmers in Minnesota. Although both groups of farmers have prior experience in food production, they face linguistic and cultural barriers as well as structural conditions such as limited land access that limit the successful growth of their businesses.

In 2012, BFRDP awarded the Latino Economic Development Center (LEDC) and their sub-awardee the Hmong American Farmers Association (HAFA) the funds to pursue the Comprehensive Intercultural Training for Beginning Latino and Hmong Farmers and Ranchers project. This project focused on developing culturally specific farming curriculum and training modules, sessions, and workshops; and encouraged a land-based cooperative approach for growing and marketing foods. By the end of the grant in 2015, it had helped Hmong farmers who had initially been selling at local farmers’ markets to cooperatively expand their sales to local groceries and a school. Latino farmers were able to develop cooperative marketing arrangements with other local farmers and arranged contracts with restaurants. This more efficient marketing resulted in increased sales and profits. On completion of this project, BFRDP awarded to HAFA as the lead and LEDC as a collaborator the funds to pursue the Beginning Farmer Training for Socially Disadvantaged Hmong and Latino Immigrants project through 2018. The new project builds upon lessons from the initial grant and takes a train-the-trainer approach to feature a culturally-appropriate curriculum delivered respectively by Hmong and Latino farmers to other Hmong and Latino farmers in their own language.

The focus on military veterans was new in the 2014 Agriculture Act, although veterans had been among the audience in a few previously funded projects. The rationale for the focus on veterans is two-fold: the skills and abilities that they developed in the military may be applicable to managing a farm or ranch, and the farm or ranch may be a hospitable or even therapeutic setting for a veteran. (Donoghue et al., 2014) While some veterans are among the audiences of many BFRDP projects, we count funds toward the 5% requirement only to the extent that the programming is specifically tailored to veterans (Box 3).

The National Center for Appropriate Technology (NCAT) has received funding from BFRDP since 2010, when it led a project that provided training to over 1,100 beginning farmers in workshops geared toward the local food market opportunities of The North Carolina Ten Percent Campaign. They also collaborated on a poultry, livestock, and agroforestry project led by the University of Arkansas that served several hundred military veterans, among other audiences (Donoghue et al., 2014).

The 2014 Farm Bill provided additional authority for BFRDP to provide preference for veteran farmer and rancher participation, by specifying at least 5% percent of funds be used for programs and services that support the needs of veteran farmers and ranchers. NCAT’s previous accomplishments led them to continue to collaborate with the University of Arkansas’s 2014 BFRDP award enhancing existing course modules to provide experiential opportunities for veterans through Armed to Farm Workshops and Trainings, developing and expanding networking, and establishing mentoring systems supporting a new generation of farmers. Through on farm demonstrations and internship programs focused on military veterans in Arkansas and Missouri, the program has continued its accomplishments and objectives into its second year. Armed to Farm has successfully sponsored 48 veterans and their families to attend the Southern Sustainable Agricultural Working Group Conference, hosted military Farmer Veteran networking session and attending the University of Arkansas VetSuccess on Campus Open House.

In FY 2016, NCAT was awarded a BFRDP grant that will serve a 100% veteran audience in Montana through a partnership with Great Falls Community College, Farmer Veteran Coalition and others, training at least 45 military veterans per year in the three year grant cycle. Their objective continues to support veteran farmers through providing intensive training, one-on-one technical assistance and partner workshops. They plan to integrate farm business planning and technical assistance. A second 2016 award to NCAT and partners will lead a similar program for veterans in Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, Massachusetts, and other northeast states.

In 2011, based on data from the first two years of projects funded in 2009 plus data from the first year of projects funded in 2010, grant recipients reported that more than 38,000 new and potential farmers participated in 5,122 BFRDP project events, including a variety of courses, workshops, and other interactions, mainly face-to-face (USDA-NIFA, 2012). The total number of participants does not account for duplication across multiple events in the same program, however. Over the next two years, a total of 56 projects funded in 2009-2012 reported more than 23,000 participants in 2012 and more than 50,000 participants in 2013, again without accounting for duplication.

We calculated the maximum number of participants in any single event, per project, and summed those numbers across projects, as a more conservative (minimum) estimate of participants served each year. This total was 9,952 in 2012 and 24,241 in 2013. The larger numbers in 2013 include the wider reach of several projects with online courses and other web-based content. For example, the University of Arkansas reported that their online course reached over 10,000 people, including 500 veterans (box 3). Nearly all BFRDP projects involve face-to-face interactions, but the addition of online courses and other web-based content is becoming more common.

For projects that reported participation by target audience, the audience breakdown is shown in Figure 3, again calculated as the sum of the maximum per project for each audience, to avoid duplication. The relatively low number for veterans reflects the fact that veterans were not a target audience for BFRDP until the 2014 Agriculture Act. The relatively large number of Native American participants in 2012 is due to one project that worked across 13 communities in its final year. The total of all socially-disadvantaged, limited-resource and farmworker participants is 54% of the total number of participants for whom demographic data were reported, well over the 25% target in the farm bill at the time, although this estimate is approximate since not all projects reported demographic data.

Since its inception, BFRDP and its grantee partners have had a strong focus on tangible results. This includes helping people enter farming and ranching, and helping those who are in their first decade of farming or ranching be more successful in tangible ways: more profitable, better stewards of the land, or stronger contributors to their communities. NIFA and its national clearinghouse partners have worked with grantees on a set of metrics to use in reporting project results (USDA-NIFA, 2015). Measures include the number or percentage of the audience for a project (or a project component) who learn something new, decide to take an action, or do take an action. These results are measured soon after project activities (for example, a survey at the end of a workshop or course) or in follow-up later in the project.

In the first round of projects—those funded 2009-2012—the shared outcome measures and the systems for tracking them across multiple projects were developed and adjusted over the course of the projects. As a result, we do not have a complete and consistent set of data for outcome analysis of those projects. Most projects reported some measures, but not every project reported on every type of measure. We do have considerable partial data that provide some insights into cumulative results and a basis for improving the future collection and reporting of data.

Based on surveys taken after training events during the first two years of BFRDP by those projects that reported data, 81-85% of participants experienced an increase in knowledge, attitude or skill (USDA-NIFA, 2012). In 2012 and 2013, 85% of participants reported a change in knowledge, attitude or skill for those projects reporting on knowledge measures.

Those projects that were able to assess changes in behavior in 2010 or 2011 reported that 57-63% of participants changed farming practices after one or two years, and 26-30% changed business practices (USDA-NIFA, 2012). In 2012 and 2013, 43% of participants reported a change in farming or business practices.

Collecting and aggregating data on participation and results across very diverse projects has been very challenging. The data cited above were pulled from annual project reports by the BFRDP clearinghouse at the National Agricultural Library (NAL) in the early years, and then entered by project directors or extracted by NAL in subsequent years. This experience informed improvements that were made with the new clearinghouse award to the University of Minnesota Center for Farm Financial Management (CFFM). The Results Verification System that CFFM developed for BFRDP can be seen online at the Farm Answers website (CFFM, 2016a). This website usefully leverages the CFFM’s considerable experience by incorporating information from their Risk Management Education Program (CFFM, 2016b).

BFRDP recently funded a retrospective evaluation of the projects funded in 2009-2012, to take place in 2016 and 2017. The project team will identify short, medium and long-term outcomes of funded projects, through content analysis of project reports and a survey of project directors. The results will be used to identify factors contributing to successful outcomes and to make recommendations to improve program operations and future outcome reporting and evaluation methodologies.

BFRDP and other USDA programs receive valuable public input from the USDA Advisory Committee on Beginning Farmers and Ranchers, and BFRDP and its funded partners benefit from the improvements to programs and the coordination across the Department in evidence at the USDA new farmer web site (USDA, 2016).

Agricultural Act of 2014, Section 5301.

Center for Farm Financial Management (CFFM). 2016a. Farm Answers. Available online: https://farmanswers.org/

Center for Farm Financial Management (CFFM). 2016b. Extension Risk Management Education, Completed Projects. Available online: http://extensionrme.org/Projects/CompletedProjects.aspx?y=2015&i=0

Consolidated Farm and Rural Development Act of 2003, Section 355 (e).

Donoghue, D.J., H.L. Goodwin, A.R. Mays, K. Arsi, and M. Hale. 2014. “Armed to Farm: Developing Training Programs for Military Veterans in Agriculture.” Journal of Rural Social Sciences. (29.2):82-93.

Farm Security and Rural Investment Act of 2002, Section 7405.

Thilmany McFadden, D., and S. Sureshwaran. 2011. "Theme Overview: Innovations to Support Beginning Farmers and Ranchers". Choices. Quarter 2. Available online: http://choicesmagazine.org/choices-magazine/theme-articles/innovations-to-support-beginning-farmers-and-ranchers/theme-overview-innovations-to-support-beginning-farmers-and-ranchers

U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Institute of Food and Agriculture (USDA-NIFA). 2012. “Outcomes Report 2011.” Available online: https://nifa.usda.gov/sites/default/files/resources/Beginning%20Farmer%202011%20Outcomes_0.pdf

U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Institute of Food and Agriculture (USDA-NIFA). 2013. “Educational Enhancement Projects: Years 2009-2012.” Available online: https://nifa.usda.gov/sites/default/files/resource/eep_summaries.pdf

U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Institute of Food and Agriculture (USDA-NIFA). 2015. “Outcomes Based Reporting Guide for BFRDP.” Available online: https://nifa.usda.gov/resource/outcomes-based-reporting-guide-bfrdp-1115-update

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). 2016. “New Farmers: Discover it here.” Available online: www.usda.gov/newfarmers

Williamson, J. 2014. “Beginning Farmers and Ranchers and the Agricultural Act of 2014.” Amber Waves, June 2, 2014. Available online: http://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2014-june/beginning-farmers-and-ranchers-and-the-agricultural-act-of-2014.aspx