Following more than a decade of uncertainty and changing exemption levels, the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 made the estate tax law permanent with a $5.25 million exemption amount (potential $10.5 million for married couples) for 2013 and a 40% top tax rate. The exemption is indexed for inflation. At this level it is estimated that only about 0.2% of all estates will owe federal estate tax (Harris, 2013). However, the share of farm estates subject to the tax is expected to be slightly higher.

Farmers and owners of other small businesses hold significant amounts of wealth in the form of business assets and are thus more likely than other taxpayers to be subject to the federal estate tax. Concern for the impact of the federal estate tax on the ability to transfer the farm to the next generation has been a primary factor in increasing exemption levels and special provisions targeting farmers and other small business owners. The appreciation in land values and the rising investment in farm machinery and equipment have increased farm estate values. As of 2010, the median net worth of farm operator households was $576,745 (USDA, 2013), which is more than seven times the $77,300 median net worth for all U.S. households (Bricker, 2012). In fact, since 2000, average farm household net worth has nearly doubled (USDA, 2013). Farm net worth accounts for about 80% of average farm household net worth and farm real estate accounts for nearly 80% of total farm equity.

The impact of the new estate tax exemption levels can be estimated using information regarding farm assets and liabilities for farm operator households from the Agricultural Resource Management Survey (ARMS). Based on simulations using farm-level survey data from the 2011 ARMS, only about 1.4% of the 41,131 individual farm estates projected for 2013 are estimated to have assets in excess of $5.25 million and would be required to file an estate tax return. After deductions, only about half of these farm estates are likely to owe any tax. These taxable farm estates are estimated to have an average net worth of $ 11.2 million—including non-farm wealth—with the average taxable estate owing about $1.83 million for a total estimated federal estate tax liability of $524 million.

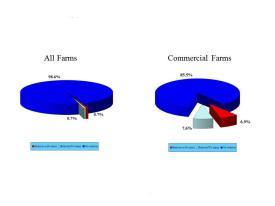

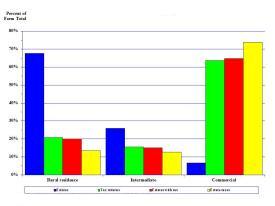

The impact of the federal estate tax varies by farm size. While the wealth of households associated with rural residence (small farms with a retired operator or a primary occupation other than farming) and intermediate farms (farms with sales less than $250,000 but a primary occupation of farming) has grown slowly since 2008, the wealth of households operating commercial farms (those with sales of $250,000 or more) increased by 30 percent from 2009 to 2011. The different increases in wealth are primarily because commercial farm households own more farmland, which has appreciated rapidly in recent years (USDA, 2013). A relatively larger share of commercial farms is projected to owe federal estate taxes in 2013 (Figure 1). The average value of farm assets for commercial farms was roughly $2.9 million in 2011, based on the most recent data available from ARMS. Thus, despite the higher exemption levels and estate tax relief targeting farmland (special-use valuation), an estimated 7% of all commercial farm estates are likely to owe federal estate taxes in 2013. Commercial farms are 10 times more likely to owe federal estate taxes than other farms. While commercial farms represent only about 6% of all farm estates, they account for nearly 74% of all federal estate taxes paid by farm estates (Figure 2). In contrast, rural residence farms account for nearly two-thirds of all farm estates but only about 13.5% of federal estate taxes. These estates also tend to have a larger share of their net worth in nonfarm assets than commercial farm estates.

There is also variation in the effect of the estate tax by type of farm. While crop farms represent about 43% of all farms, they account for nearly two-thirds of taxable estates and over half of estimated federal estate taxes. In fact, crop farms involved in the production of high-value crops account for a large share of both taxable estates and federal estate taxes. These farms—which include those involved in the production of vegetables, fruit and tree nuts, and nursery and greenhouse products—are disproportionately represented among million-dollar farms and they produce over 70% of the total value of these high-value crops (Hoppe and Banker, 2010). Further, since these farms are geographically concentrated in the South and West, the share of estates that owe taxes also vary by region.

Concerns that estate taxes might cause the breakup of some family-owned farms and small businesses led Congress to include two special provisions in the Tax Reform Act of 1976. Over the years, these targeted provisions—the special-use valuation and the installment payment of estate taxes—have reduced the impact of federal estate taxes on farms with estates valued above the basic exemption. While increased exemption levels have reduced the need and the value of these special provisions, they will continue to provide significant benefit to the very large farm estates that exceed the new exemption level.

The value of property for federal estate tax purposes is generally the fair market value on the date of the property owner’s death. However, if certain conditions are satisfied, the estate’s real property that is used solely for farming or another closely held business may be valued at the property’s value as a farm or business rather than at its fair market value. The method used to value farmland for use-value purposes is to divide the 5-year average annual gross cash or share rental for comparable land in the area, minus state and local real estate taxes, by an average of the annual effective interest rate for all new Federal Land Bank (FLB) loans for the year of death. For those farms that qualify, special-use valuation generally reduces the value of the real property portion of qualifying estates by 40% to 70%, with the largest potential reductions occurring for farmland near urban areas having residential or commercial development potential.

Based on information published by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), the average reduction in value for qualifying estates in 2001 was 50%. The decline in interest rates since 2001 may cause the average reduction to be less than 50%. For estates of those dying in 2013, the tax law limits the special-use valuation reduction in value to $1.07 million. This limit is indexed for inflation. At the current 40% federal estate tax rate, the potential estate tax savings available under special-use value could be as much as $428,000. However, all or a portion of the estate tax benefits obtained under the special-use valuation provision must be repaid if the property is sold to a nonfamily member or if the property ceases to be used for farming within 10 years of the owner’s death.

Since 1998, there has been an added incentive to grant a qualified conservation easement on farmland subject to the federal estate tax. In addition to the reduction in the estate value of land for a conservation easement, an exclusion is provided for up to 40% of the value of land in an estate that is subject to a qualified conservation easement. The decedent or a member of the decedent’s family must have owned the land for at least three years prior to the date of death and the donation must have been made by the decedent or his or her family. The exclusion is based on the value of the property after the conservation easement is placed, and does not include any retained development rights to use the land for any commercial purpose except those supportive of farming. If the value of the conservation easement is less than 30% of the value of the land for purposes of the exclusion, the exclusion percentage is reduced two percentage points for each percentage point below 30%. The maximum exclusion is limited to $500,000. But at current rates, the exclusion alone can save an additional $200,000 in federal estate taxes.

Granting a qualified conservation easement is not treated as a disposition that would trigger the recapture of special-use valuation benefits, and the existence of a qualified conservation easement does not affect eligibility for special-use valuation. Thus, the exclusion can be used in combination with the special-use valuation provision. While the exclusion provides an additional incentive to donate a conservation easement, given the increased unified credit and the availability of special-use valuation, the number of landowners who are subject to the federal estate tax and who would benefit from the additional exclusion may be relatively small. Nevertheless, those farmers with very large estates and land holdings who are willing to forgo potential future development gains can reduce their taxable estate by not only the value of the conservation easement they donate during their lifetime but also another $500,000 without affecting the operation of the farm business. Because the maximum reduction is 40% the value of the property subject to the conservation easement must be $1.25 million or more at the time of his or her death to get the maximum $500,000 reduction in the taxable estate.

Federal estate taxes generally must be paid within nine months of the date of the property owner’s death. However, for certain estates with farm or closely-held business assets, estates taxes can be paid in installments. The installment payment provision was enacted out of concern that the heirs of family farmers and small business owners might have difficulty paying taxes on land and other relatively illiquid business assets. Under the provision, if at least 35% of an estate’s value is a farm or closely-held business, estate taxes may be paid over 14 years and 9 months, with only interest due for the first five years. In 2013, the interest rate on the first $1.43 million in taxable value (above the basic exemption and other exclusions) of the farm is 2%, with slightly higher rates owed on amounts above $1.43 million. Thus, the annual interest payment on this amount would only be $28,600. This installment payment provision, combined with the increase in the amount of property that can be transferred tax free, greatly reduces the liquidity problem that some farm heirs might otherwise experience as a result of federal estate taxes.

| Size of Gross Estate (million $) | Returns | Farm Property | Average Tax Rate 1/ | |||

| Number | Percent of All Returns | Amount (thousand $) | Average | Percent of Total Estate | ||

| Less than $3.5 | 21 | 12.1 | 20,094 | 956,857 | 38.9 | 8 |

| $3.5 - $5 | 44 | 15.8 | 54,801 | 1,245,477 | 29.3 | 7.6 |

| $5- $10 | 100 | 15.3 | 218,643 | 2,186,430 | 32.2 | 12.8 |

| $10- $20 | 35 | 16.1 | 93,536 | 2,672,457 | 19.6 | 20.9 |

| More than $20 | 28 | 17.9 | 105,934 | 3,783,357 | 5.5 | 16.3 |

| All | 228 | 15.4 | 493,009 | 2,162,320 | 16.1 | 15.5 |

An examination of actual federal estate tax returns filed in 2011 confirms that, compared to other taxpayers, a larger share of farmers are subject to the estate tax. Yet it also reveals that farm property is not a large part of the taxable estate, especially for larger estates (IRS, 2012). This should be expected since, compared to farm operators, these returns include those that may have reduced their involvement in the operation of the farm, reducing their ownership of farm assets through the gifting, or the sale or other transfer of farm property. This data also likely includes the estates of other individuals who owned some farm property at death but were never actively engaged in farming. Data regarding the type of property held by taxable estates suggests that publicly traded stock, state and local bonds, and cash assets are the largest holdings. While these assets are more liquid and may provide a ready source of funds to pay estate taxes, they can also affect the ability of estates to qualify for the use-value and installment payment provisions.

Of the 1,480 taxable estate tax returns filed in 2011, 228 or about 15% had some farm property in the estate, including farmland and other farm assets (Table 1). These estates reported an average of $2.162 million in farm property for a total of $493 million. Overall, this represented only about 2.5% of total assets for all taxable estates. While farm property represented about one-third of the total estate for those estates less than $10 million, it represented only about 5% of total assets for those estates larger than $20 million. The average federal estate tax rate for estates with farm property was 15.5%.

The increased exemption levels and resulting lower effective tax rates—combined with the continued availability of special provisions, including the installment payment provision—should greatly reduce or eliminate any potential liquidity problems created by the estate tax on the transfer of the farm to the next generation. Thus, while a larger share of farmers will continue to be subject to the estate tax relative to the general population, over 99% of all farm estates will be exempt and those estates that are subject to the tax should have the resources to pay the tax without selling farm property.

Bricker, J., Kennickell, A.B., Moore, K.B., and Sabelhaus, J. (2012). Changes in U.S. Family Finances from 2007 to 2010: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances. Federal Reserve Bulletin, 98(2), 1-80. Available online: http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/bulletin/2012/pdf/scf12.pdf

Harris, B. Estate Taxes After ATRA. Tax Notes, February 25, 2013. p. 1005. Available online: http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/1001660-TN-estate-taxes-after-ATRA.pdf

Hoppe, B., and Banker, D. (2010). Structure and Finances of U.S. Farms: Family Farm Report, 2010 Edition. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, EIB-66, July. http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/eib-economic-information-bulletin/eib66.aspx

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. (2013). Farm Household Wealth and Income. Available online: http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/farm-household-well-being/wealth,-farm-programs,-and-health-insurance.aspx

U.S. Department of Treasury, Internal Revenue Service. (2012). Selected Income, Deduction and Tax Computation Items, by Tax Status and Size of Gross Estate. Available online: http://www.irs.gov/uac/SOI-Tax-Stats-Estate-Tax-Statistics-Filing-Year-Table-1