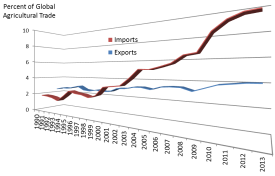

China’s imports of agricultural products are growing. Rising living standards and urbanization are creating new demands for food, while environmental and resource constraints limit growth in domestic production. Imports are outpacing agricultural exports, and China is becoming a larger net importer of farm products.

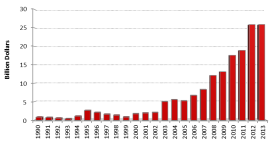

With abundant natural resources and efficient farmers, the United States is the leading supplier of many of China’s major agricultural imports. The United States accounted for over 24% of China’s agricultural imports by value during 2012-2013 (Gale, Hansen, and Jewison, 2015). U.S. agricultural exports to China grew from $1.9 billion during 2001—the year of China’s WTO accession—to $26 billion in 2013. China was the 7th largest market for U.S. agricultural exports in 2001 and is now the top overseas market for U.S. food and fiber. The share of U.S. agricultural exports going to China rose from 2-to-3% during the 1990s to 18% now.

Source: Analysis of data from World Trade

Organization.

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture,

Global Agricultural Trade System.

While China’s growth creates new potential markets for U.S. agricultural products, it also creates new uncertainty and tensions. As China becomes a bigger customer for U.S. agricultural products, disputes seem to multiply:

China is sending conflicting signals about its engagement in agricultural markets. There are signs that Chinese officials are moving toward a greater participation in agricultural trade. At the same time, officials also appear determined to exert tight control over imports.

When China joined the WTO in 2001, it committed to relatively low agricultural tariffs, elimination of import quotas for most commodities, science-based standards for imported commodities, and limits on domestic support programs. Chinese leaders say WTO accession was beneficial for agriculture, since it opened the sector to outside investment and technology, boosted agricultural exports, helped alleviate rural underemployment, and renewed momentum on market reforms (Han, 2011; Niu, 2011). Officials endorse participation in multilateral trade organizations like WTO where they hope to promote the interests of China and other developing countries (Agricultural Trade Promotion Center, 2014; Caixin Net, 2015). China has negotiated free trade agreements with a number of agricultural exporters, including U.S. competitors like Australia and New Zealand, which will cut tariffs on imports of dairy, beef, and sorghum from those countries. Some measures, like a cut in tariffs on pistachios and almonds in 2015, reflect consumer demand for new products that are not widely produced in China. President Xi Jinping’s farm visits and discussions of agriculture in trips abroad are described by official media as a “farm diplomacy” strategy that reflects his endorsement of international cooperation in agriculture (Peoples Daily, 2014). Speeches and articles by agricultural officials endorse a “two markets, two kinds of resources” strategy that advocates meeting China’s growing demand for food with both domestic and international commodities. A reflection of the increasing role of trade is the inclusion of agricultural trade and foreign investment policy recommendations in the communist party’s annual “Number one documents” during 2014-2015.

China’s commitment to free trade in agricultural markets is tempered by perceived threats to food security and domestic stability. A new food security strategy introduced in 2013 acknowledges a necessary role for imported commodities in China’s food supply, but it also calls for ensuring that domestic supplies retain a dominant role while imports are limited to a supplementary role (Han, 2012; Han, 2014; Han and Jin, 2014). Officials worry that imports and foreign investment threaten the development of domestic industries and reduce the government’s ability to control production and prices (Niu, 2011). Moreover, officials are concerned that agricultural imports could restrain rural income growth and spread discontent in the countryside. Ancillary objectives—all represented in the 2014 “Number one document”—include diversifying import sources, stabilizing domestic prices, and ensuring “industry security”, that neither imports nor foreign companies undermine the dominant position of Chinese producers and processors in any particular sub-sector.

With so many objectives, Chinese officials frequently see reasons to intervene in markets. Most of the intervention is in the domestic market through buying and selling commodity reserves and by subsidizing production, transportation, storage, and processing of commodities. China’s Minister of Agriculture cited policy support as the most important factor contributing to eleven straight increases in grain production from 2004 to 2014 (Han, 2014). Officials reported that “policy purchases” equaled about 20% of the 2014 grain harvest. More than half of China’s cotton is produced with subsidies in the northwest region and requires additional transportation subsidies for the long journey to textile mills in eastern provinces (MacDonald, Gale, and Hansen, 2015). Similar transportation subsidies were given for corn produced in northeastern provinces during 2013, and starch and alcohol processors were given subsidies for each ton of domestic corn they processed during 2014.

Interventions at the border can vary with market conditions. The Minister of Agriculture advised officials to “keep a good grip on the volume and timing of imports to prevent large concentrated imports of any commodity from pressuring domestic production or having unfavorable impacts on farmers’ incomes” (Han, 2014). Similar language about regulating the flow of imports to stabilize domestic markets has appeared in documents since the 1990s and was included in the 2014 and 2015 “Number one documents.” Interventions to slow imports include the withdrawal of “sliding scale” cotton import quotas and tighter control over distribution of grain TRQs. Increased attention to inspections and enforcement of bans on feed additives and genetically modified crops tend to occur during periods of excess supply in the Chinese market.

Suspicions that inspection and quarantine measures are manipulated to manage the flow of trade are supported by official documents that endorse such practices.

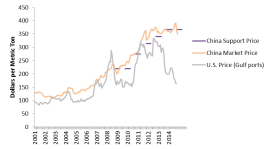

China’s rising level of domestic support for agriculture has raised trade tensions. Chinese officials are pursuing numerous intervention programs modeled on policies used by countries in North America and Europe during the last century. And like those 20th century programs, China’s interventions have led to confusion and disruptions in international markets.

Note: China prices converted to U.S.

dollars at the official exchange rate.

Source: China National Development and

Reform Commission, China National Grain

and Oils Information Center, and U.S.

Department of Agriculture.

When China joined the WTO, its domestic support for farmers was minimal. A package of small subsidies and tax cuts introduced during 2004-2006 was popular with farmers, but the benefits were eroded by rising production costs. After 2008, authorities began to raise price supports annually to maintain production incentives and rural income growth (Gale, 2013). Now China’s farm prices exceed global prices for nearly all major commodities, and authorities have accumulated large stockpiles of cotton, grains, edible oil, and sugar.

China’s commitment to free trade in agriculture may be tested as officials find themselves hemmed in by downward pressure on domestic prices, excessive stockpiles, and relatively low barriers to imports. In 2015, Chinese officials say their policy support for agriculture faces “two ceilings and one floor” (Economic Daily, 2015). The “floor” is rising production costs which reduce net margins for producers. Domestic prices cannot be raised further above the “ceiling” of international prices—support prices were held steady during 2014, after five years of increases. Soybean and cotton price supports were abandoned, and authorities are experimenting with direct subsidies for these commodities to replace price supports. This policy change is constrained by a second “ceiling”: officials say the country’s farm subsidies have already reached the 8.5% limit on “amber box” measures prescribed by WTO commitments. As of 2014, China had only notified its domestic support to WTO through 2008, but support has increased rapidly since then (Gale, 2013).

Chinese officials say that they take their WTO commitments seriously and aspire to influence the rules for international trade through participation in such international organizations (Niu, 2011; Caixin Net, 2015). They designed their domestic support policies to conform to WTO requirements, and Chinese authorities have refused some demands from soybean, sugar, and distilling industries for antidumping and countervailing duties. However, practices like tight controls over TRQ distribution, opaque and lengthy approval processes for genetically modified crops, and uneven application of inspection and quarantine regulations seem to skirt the rules and add uncertainty to trade. China’s future paths for domestic support, food safety regulation, and its approach to producing and importing genetically modified crops are also uncertain.

China’s engagement with the global market is related to a wide range of domestic institutional reforms now underway to reduce barriers to rural-urban migration, improve banking services for agriculture, promote rural land markets, and strengthen mechanisms for innovation in agricultural science and technology. The need for such reforms has been recognized for many years (Lohmar et al., 2009), and the decision to finally move forward on such reforms appears to have been spurred by food security concerns and eroding international competitiveness. Chinese officials say new initiatives to increase the scale of farms are intended to raise productivity in order to improve the competitiveness of farms (Caixin Net, 2015). The reform push suggests that Chinese leaders do not intend to shelter uncompetitive small-scale farms behind a barrier of protection as several other East Asian countries have done (Otsuka, 2013).

China is pursuing free trade agreements and encouraging outbound investment in agricultural processing, logistics, and farming to secure supply chains for imported commodities. The outcome of these initiatives and their impacts are all uncertain. Moreover, a financial crisis or the onset of deflation could reverse the rapid growth in rural wages, land rents, and nominal currency appreciation that contributed to rapid growth in Chinese commodity prices in recent years. Just as an unanticipated decline in global agricultural prices created China’s “two ceilings and one floor” quandary, a rebound in global prices could improve China’s competitive position.

Farmers and leaders in business and government worldwide are trying to anticipate China’s future role in agricultural trade. While extrapolating past trends is the easiest way to forecast the future, observers should prepare for a variety of possible scenarios. China is in a critical period where extrapolation of past trends may no longer be valid. China’s agricultural imports could continue growing (or even accelerate) if economic growth is sustained and officials reduce their intervention. Conversely, permanently slower economic growth or reversal of reforms could slow agricultural imports. Therefore, monitoring production, consumption, trade, and policy in China may be more important than ever.

Agricultural Trade Promotion Center, MOA. 2014. Agricultural Trade Research 2009-13. Beijing: Agricultural Press.

AQSIQ (General Administration for Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the PRC). 2014. “Zhi Jian Zong Ju Guanyu Jia Qiang Jinkou Yumi, Gaoliang, Damai Deng Liangshi Jianyan Jianyi Yinguan Gongzuo de Tongzhi [AQSIQ Circular on Strengthening Work on Supervision, Testing, and Quarantine for Imported Corn, Sorghum, Barley and Other Grains],” circular 342.

Caixin Net. 2015. Cheng Guoqiang: Zhongguo Liangshi Anquan de Zhen Wenti [Cheng Guoqiang: The Real Issues for China’s Food Security]. February. Available online: http://opinion.caixin.com/2015-02-05/100781776.html

Economic Daily. 2015. “’Di Ban Jia’ Bu Duan Shang Sheng, ‘Tian Hua Ban’ Bu Duan Xia Ya [Floor Price Continually Rises, Ceiling Continually Exerts Downward Pressure], Available online: http://paper.ce.cn/jjrb/html/2015-01/07/content_227923.htm.

Gale, F. 2013. Growth and Evolution in China's Agricultural Support Policies. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, ERR-153.

Gale, F., J. Hansen, and M. Jewison. 2015. China’s Growing Demand for Agricultural Imports. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, EIB136. Available online: http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/eib-economic-information-bulletin/eib136.aspx

Gale, F., D. Marti, and D. Hu. 2012. China’s Volatile Pork Industry. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, LDPM-21101. Available online: http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/ldpm-livestock,-dairy,-and-poultry-outlook/ldpm211-01.aspx.

Han, C. 2011. “Ru Shi Shi Nian yu Zhongguo Nongye Fazhan [Ten Years in WTO and China’s Agricultural Development].” Farmers Daily, December. Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/zwllm/zwdt/201112/t20111226_2443081.htm

Han, C. 2014. “Quanmian Shishi Xin Xingshi Xia Guojia Liangshi Anquan Zhanlue [Fully Implement the Strategy for National Food Security in a New Situation],” Qiushi. Available online: http://www.qstheory.cn/dukan/qs/2014-10/01/c_1112659825.htm

Han, J. 2012. Food Security Strategy for 1.4 Billion People. Beijing: Xuexi Publishing House.

Han, J., and S. Jin. 2014. “Mai Xiang Gao Shou Ru Guo Jia de Zhongguo Liangshi anquan Zhanlue yu Zhengce Yanjiu” [Strategy and Policy Research on Food Security as China Strides Toward Becoming a High Income Country]. China: Food Security and Agricultural Going Out Strategy Research. Beijing: China Development Press, 2014.

Lohmar, B., F. Gale, F. Tuan, and J. Hansen. 2009. China’s Ongoing Modernization: Challenges Remain After 30 Years of Reform. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, EIB-51. Available online: http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/eib-economic-information-bulletin/eib51.aspx.

MacDonald, S., F. Gale, and J. Hansen. 2015. Cotton Policy in China. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, CWS-15c-01. Available online: http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/1813054/cws-15c-01.pdf

National Development and Reform Commission (China). 2009. “Fangzhi Shengzhu Jiage Guodu Xiadie Tiaokong Yu'an [Adjustment Plan for Preventing Excessive Declines in Hog Prices],” document no. 1.

Niu, D. 2011. “Zhongguo Nongye Ru Shi Shi Zhou Nian Huigu yu Zhanwang [Chinese Agriculture’s Tenth Year in WTO: Retrospect and Prospects].” Issues in Agricultural Economy, December.

Niu, S., and D. Patton. 2014, August 21, “China Tightens Checks on U.S. Sorghum Imports,” Reuters. Available online: http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/08/21/china-sorghum-usa-idUSL4N0QP1RW20140821.

Otsuka, K.. 2013. “Food insecurity, income inequality, and the changing comparative advantage in world agriculture,” Agricultural Economics, Vol. 44, Issue s1, pp 7–18.

Peoples Daily, 2014, July 29 “’Nongzhuang Waijiao’ Zhongguo de Jia Guoqinghuai – Xi Zhuxi La mei Xing Shu Ping Zhi Si [Farm Diplomacy’s National Identity—Review of Chairman Xi’s Latin American Visit].” Available online: http://cpc.people.com.cn/n/2014/0729/c64387-25359844.html

Xi, Y., and L. Yang. 2013. “Wo Guo Yumi Gong Qiu Xingshi he Jinkou Qianjing Fenxi [Analysis of Our Country’s Corn Supply and Demand Situation and Import Prospects],” Ministry of Agriculture, Research Center for Rural Economy, Zhongguo Nongcun Yanjiu Baogao, Beijing: China Financial and Economic Publishing House, pp. 439-451.

Weihai Evening News. 2014. Weihai Shi Shouhuo Dami Jinkou Guan Shui Pei’e, Tianbu Pei’e Liyong Kongbai [Weihai Municipality Gets Rice Import Tariff Rate Quota, Fills Space for Quota Utilization], 14 January (in Chinese). Available online: http://www.whnews.cn/news/node/2014-01/15/content_5926033.htm.