Largely due to their own policy choices over time, livestock and specialty producers do not benefit from farm safety net programs like producers of field crops, which are provided under the Commodity Title of farm bills. Although they do participate to some degree, these producers do not rely on the federal crop insurance program either. Instead, the major forms of current support for these producers provided through the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) are discussed in this article, including efforts to expand both domestic and international demand, funding to ensure the wholesomeness of their products and environmental sustainability of their operations, and disaster assistance. It does not cover the suite of smaller programs aimed at fostering local and regional marketing of food or those focused on enabling organic production and marketing.

The traditional farm safety net programs provide financial support for a minority of American farmers and ranchers from the federal government. These programs are focused on bolstering the income of farmers producing the major row crops and milk. According to data collected in the 2012 Census of Agriculture, the federal government provided no payments whatsoever to more than 60% of Census farms, and some of the payments that were made came out of conservation and loan programs that are not part of the formal farm safety net. Of the roughly 800,000 farmers who did receive some payments, nearly 60% received $5,000 or less in 2012.

Roughly half of the nation’s farms are predominantly livestock operations, and about 9% specialize in vegetables, fruit, or nursery crop operations. As of the latest USDA estimates for total agricultural receipts from August 2016, livestock and dairy account for roughly the same share of total agricultural receipts as number of farming operations at 48%, while specialty crop production is expected to generate 27% of total receipts, or about three times their share of producers.

Until relatively recently, farmers whose primary on-farm activities were not raising field crops or dairy cattle were content to not receive substantial direct federal financial assistance. In fact, certain groups of those farmers took pride in this status--livestock producers often characterized themselves as 'rugged individualists' not needing to rely on federal farm support. However, this description does not acknowledge benefits that cattlemen from the Western United States derive from the availability of public grazing land at relatively low cost per animal unit rented from one or more federal agencies such as the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the U.S. Forest Service. Both Western livestock and specialty crop producers also benefit from large federal investments over the years in water and hydroelectric projects, with the Bureau of Reclamation and the Army Corps of Engineers building infrastructure such as dams, canals, tunnels, and aqueducts. According to a 2006 study by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the federal government spent $24 billion—in nominal dollars—on such projects between 1902 and 2004, although a share of that investment was eventually reimbursed by beneficiaries.

In addition to the below-market cost access to land, water, and electricity that many livestock and specialty crop farmers have received over time due to the federal but non-USDA efforts described above, some of these farmers have also benefitted from USDA programs that are broadly available to producers of all types of commodities.

Until the last few farm bills, rather than pursue direct benefits through the farm bill process, commodity associations representing livestock and horticultural producers primarily focused on maintaining or increasing resources for programs which helped to expand the demand for their products, either domestically through nutrition assistance programs such as the school lunch and breakfast programs or internationally through USDA trade promotion programs. For example, during the mid-1990's, the U.S. Department of Defense ordered its domestic procurement officials to purchase fresh fruit and vegetables for distribution to school systems located near U.S. military installations in addition to the purchases it would make for food preparation facilities serving the military personnel and dependents living on those bases. This effort was institutionalized as a specific provision in the Food Security and Rural Investment Act of 2002. The so-called DOD Fresh program now provides assistance to school districts beyond those located near military installations. Periodically, the Secretary of Agriculture also uses a longstanding authority, under Section 32 of the Act of August 24, 1935 to procure commodities for distribution within the school lunch program if those commodities are deemed to be in surplus or their producers are seen as facing economic distress. This 'emergency removal' procedure was used to purchase turkey, fruits and vegetables, and chicken products valued at $200 million in fiscal year 2013. The flexibility of Section 32 was reduced somewhat by language included in the 2008 farm bill, but it still serves as a tool of last resort to help U.S. producers not covered under traditional safety net programs.

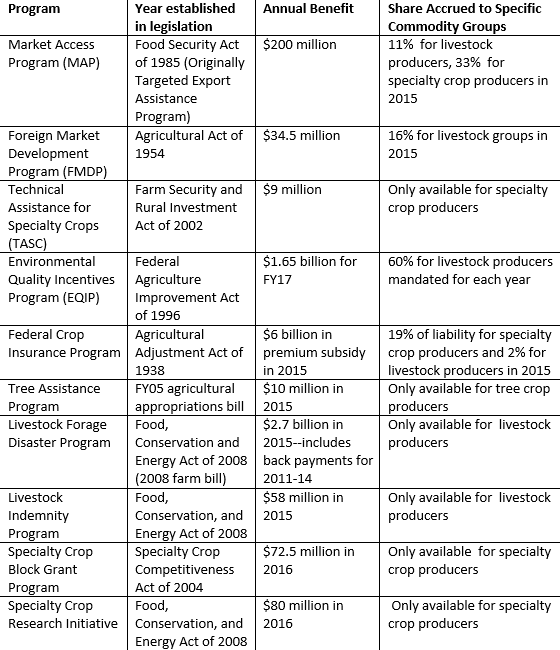

Sources: Agricultural Act of 2014 (for mandatory programs, FY17 USDA Budget Summary,

FAS/USDA (for shares of trade promotion programs), OBPA/USDA Budget Tables.

On the trade side, both specialty crop and livestock groups are major participants in the two main trade promotion programs operated by USDA's Foreign Agricultural Service, the Market Access Program (MAP), funded at $200 million annually, and the Foreign Market Development Program (FMDP), funded at $34.5 million annually, both with mandatory Farm Bill money. MAP funding tends to support generic promotion efforts in targeted markets, while FMD funds are focused more on efforts to ensure that foreign markets stay open to U.S. products. Meat and livestock groups received $19 million in MAP funds in fiscal year 2016 (FY16)-about 11% of the total allocated--while fruit, vegetable, and tree nut groups received $58 million—33% of the total (Table 1). The livestock funding primarily went to the U.S. Meat Export Federation, while the specialty crop funds went to a variety of state groups—especially from California—national commodity groups, and a handful of large grower cooperatives, such as Sunkist and Welch's. Meat and livestock trade associations—and exporters of related products such as hides and skins and animal semen) also received about 16% of the funds provided under FMDP for FY16.

On the trade promotion side, specialty crop stakeholder groups were also able to obtain farm bill funds for a separate program focused entirely on their trade issues, called Technical Assistance for Specialty Crops, or TASC. This program first received modest funding of $2 million annually under the 2002 farm bill, with funding ratcheted up from $4 million to $9 million annually under the 2008 farm bill, and maintained at $9 million annually under the 2014 farm bill. The program provides funding to U.S. organizations for projects that address foreign sanitary, phyto-sanitary and technical barriers that prohibit or threaten the export of U.S. specialty crops, with approved projects receiving up to $500,000. Trade associations or other organizations participating in the MAP and FMDP are required to provide their own funds to match what they receive under the program, while such matches are encouraged though not required for TASC applicants.

When the federal crop insurance program (FCIP) was established in 1938, it was aimed solely at producers of key row crops in major producing regions, such as wheat, corn, and cotton. The program limped along with low participation and relatively little public support for several decades until the passage of the Federal Crop Insurance Act of 1980, which made several significant changes in the program. Coverage was expanded into new crops and regions. Federal premium subsidies were offered for the first time to defray the cost to producers and thus encourage more participation in the program. Also, for the first time, private sector insurance companies were allowed to sell and service FCIP policies.

Today, although the program remains focused on row crops in terms of value of crops and total acres insured that the top four crops—corn, soybeans, wheat, and cotton—accounted for 75% of the program's liability in 2015--affirmative steps have been taken in recent decades to facilitate coverage for a broad range of specialty crops and to a lesser extent for livestock production. Beginning with the Agricultural Risk Protection Act of 2000 (ARPA), a mechanism was established to provide an opportunity for outside stakeholder groups to develop proposed crop insurance products for additional crops or livestock, and if those proposals were approved by the Board of the Federal Crop Insurance Corporation (FCIC), receive reimbursement for expenses incurred. In the 2008 farm bill, this policy submission mechanism was modified to allow groups to also request funds for policy development in advance of their detailed work, up to 50% of the estimated costs, rather than wait for reimbursement after the policy is approved. In February 2015, USDA's Risk Management Agency (USDA-RMA) announced that groups developing a new crop insurance policy could collect up to 75% in advance rather than 50% if that work was focused on specialty crops or underserved producers.

As a result of the new mechanism for private sector development of crop insurance products in ARPA, access to such coverage has expanded greatly for both specialty crop and livestock producers. Although the number of specialty crop policies sold declined by about 10% between 2000 and 2015, as have policy counts generally, the liability for those crops—their insured value—rose by more than 150% over the same period, from $7.6 billion to $19.5 billion. Part of this increase is due to higher prices, but a portion is due to the fact that many specialty crop producers now have access to higher coverage levels under buy-up policies, as opposed to the catastrophic policies that were the main type of insurance available previously.

Livestock producers have two different paths to participate in the federal crop insurance program. Hog and cattle producers have access to coverage against declines in the value of their animals when they take them to market, although the federal cost of such programs was capped by statute in ARPA at $10 million annually. These products never caught on. In 2015, only about 2,400 producers purchased such policies, with total liability of $1.3 billion, or about 1% of the liability insured under the crop side of the program. In addition, farmers who graze their animals on pasture or rangeland also have access to insurance against loss of the forage they need for those animals. Indemnity payments for these policies are based on changes in precipitation or temperatures in the area where the animals are grazing, rather than losses in specific fields as is the case with most crop insurance policies. In 2015, the liability of these rangeland and pasture policies was $1.1 billion, a 400% increase over 2000 levels.

The 2008 farm bill established a set of five stand-alone disaster assistance programs. Four of the programs were targeted at least in part to assistance for producers of livestock and certain specialty crops. Livestock owners whose animals die as a result of a natural disaster such as floods or blizzards are eligible for payments under the Livestock Indemnity Program, and livestock producers whose access to good quality forage is reduced due to drought or fires can receive payments from the Livestock Forage Disaster Program. The 2008 farm bill also provided funds to continue the Tree Assistance Program (TAP), which gives owners of orchards or nursery trees a payment if their trees, bushes, or vines are lost as a result of a natural disaster. This program is distinct from the crop insurance indemnity a farmer would receive as a result of a lost tree crop, such as apples or oranges in a given season, because the latter assumes that the trees would still be there to bear fruit in subsequent years. An ad hoc program to help tree producers had first been created in the fiscal year 2005 omnibus appropriations bill. The Emergency Assistance for Livestock, Honey Bees, and Farm-Raised Fish (ELAP) is designed to provide assistance for losses by livestock producers not otherwise covered under other programs, such as losses due to cattle tick fever treatment or the cost of moving animals to alternative watering sources if a drought dries up their normal sources. The other program was the Supplemental Revenue Assistance Program (SURE), available to help all crop producers

All of the programs except for SURE were re-authorized in the 2014 Farm Bill, and mandatory funding for four of the continued programs (excluding ELAP) was left intact without caps. In fiscal year 2015, USDA estimates that more than $2.7 billion was disbursed under the Livestock Forage Disaster Program, $58 million for the Livestock Indemnity Program, and $10 million for the Tree Assistance Program. Due to the expiration of these programs in 2011, the disbursements in FY2015 covered multiple years of losses for many farmers that occurred during the period when the coverage had lapsed.

Beginning with the 2002 farm bill, the commodity organizations representing specialty crop and livestock producers shifted their attention to potential benefits that would be specifically targeted at their members. Despite this change in approach, these groups deliberately chose not to adopt the conventional safety net model used to provide income support for program crop producers. This attitude stemmed from a widely held concern that such a program would make raising specialty crops more financially attractive, inducing some row crop producers to shift some of their cropland out of row crops into growing fruits and vegetables, potentially flooding specialty crop markets and driving down prices. According to the 2012 Census of Agriculture, there were 253 million acres planted in row crops that year, as opposed to about 10 million acres with vegetables, fruit, or tree nuts. Thus, a 5% shift of row crop acres into specialty crops in one year would more than double total area under specialty crops. In fact, beginning in 1996, these groups insisted that farm bills bar program crop producers who received direct payments from planting specialty crops on any of their program base acres, fearing that the direct payment would amount to ‘cross-subsidization’ of their specialty crop production. This requirement remained in place until the direct payment program was eliminated in the 2014 farm bill, a rule that was known as a planting flexibility restriction.

Specialty crop groups were able to secure $160 million in assistance for their members in an August 2001 emergency piece of legislation intended to support U.S. agriculture in response to financial losses suffered as a result of weak global markets. This provision was included in an assistance package that totaled $5.5 billion. The legislation required USDA to distribute the money to the 50 state departments of agriculture, allocated based on states’ share of U.S. specialty crop production.

After getting their first taste of disbursal of direct funds in 2001 on an ad hoc basis, specialty crop producers initiated overtures to their members of Congress for regular, targeted federal funding to assist with domestic market issues for their products. The Specialty Crop Competitiveness Act (SCCA) which authorized several programs to help specialty crop producers with their marketing, promotion, and research needs was enacted in 2004, but none of the newly created programs received any funding until 2006. In that year’s agricultural appropriations bill, the Specialty Crop Block Grant program, modeled on the ad hoc disbursement mechanism used in 2001, received $6.5 million in discretionary funding.

The push to provide mandatory funding for this program and several others authorized in the SCCA in the 2008 farm bill was led in the Senate by Senator Debbie Stabenow (D, MI), and in the House by Representative Jim Costa (D, CA), from California’s Central Valley, both members counting a fairly large number of specialty crop producers among their constituents. This effort resulted in the establishment of the first horticulture and organic agriculture title in a farm bill, with programs for which $1 billion in funding would be provided over a ten year period, from 2008-2017. That figure was 10% of the net mandatory funds added to the 2008 farm bill above baseline levels.

In addition to the Specialty Crop Block Grant program, which received $466 million in the 2008 farm bill, the specialty crop sector obtained $377 million to fund state efforts to monitor specialty crop pests and disease outbreaks and another $20 million to set up “clean plant centers” that would provide pathogen-free propagative plant material to state agencies or private nurseries.

The last piece of the specialty crop pie was $230 million in funding—over ten years—for specialty crop research, which was included in the agricultural research title, not the horticulture and organic agriculture title. Unlike most recent efforts by the Agriculture Committees to provide mandatory funds for agricultural research through the farm bill process, these funds actually went for their intended purposes, rather than being diverted by the Agricultural Appropriation Subcommittees to pay for other items in the annual appropriations bill.

In the next farm bill, Senator Stabenow had moved up to become the chairwoman of the Senate Agriculture Committee. The horticulture title in 2014 farm bill received an additional $694 million over baseline levels over the 2014-2023 period, with additional funds for the Specialty Crop Block Grant program accounting for nearly 40% of the total increase. In addition, the specialty crop research initiative received $745 million in new funds in the 2014 farm bill. These increases occurred in the context of a farm bill that actually spent $16.5 billion less than would otherwise have occurred under baseline levels, according to CBO scoring estimates of the legislation at the time of passage.

In fiscal year 2015, USDA-AMS distributed $72.5 million to state departments of agriculture under the Specialty Crop Block Grant Program. Based on states’ share of specialty crop production, the same basic formula used since 2001, California ($19.8 million), Florida ($4.1 million), North Dakota ($2.6 million) and Michigan ($1.9 million) were the largest recipient of funds. The size of the North Dakota share was due primarily to their production of pulse crops like dry peas and lentils.

Livestock groups focused on obtaining financial assistance for their members operating large confined animal feeding operations, also known as CAFO's, who were facing increased regulatory pressure to manage the manure being produced by their animals without polluting the ground and surface water supply near their farms. The vehicle that was chosen to provide this assistance was the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), which was established as a discretionary program in the 1996 farm bill and had received annual funding which ramped up from $130 million in 1996 to $200 million in 2001.

Testimony in support of this effort was offered by the then-President of the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association (NCBA) before the House Agriculture Committee in 2001. His testimony was also endorsed by groups representing the other major groups representing animal agriculture in the United States, including hogs, sheep, dairy, and poultry producers. One of the main Congressional advocates of this approach was Representative Frank Lucas (R, OK), at the time chairman of the subcommittee with jurisdiction over conservation programs. In the 2002 farm bill, EQIP's funding was increased significantly, starting at $545 million in 2002 and ramping up to $1.16 billion by 2007, and was switched from discretionary to mandatory funding. To address the 'ask' sought by livestock groups, Congress included in that legislation a requirement that at least 60% of EQIP funds be allocated to livestock operations, primarily to underwrite those farmers' efforts to manage their manure in compliance with state and federal regulations. A March 2007 study by the Soil and Water Conservation Society on the EQIP program found that for 2005, the average EQIP contract involving livestock production received one-third more funds than EQIP contracts involving primarily crop production, at more than $19,000 as compared to $14,000. EQIP is scheduled to receive $1.65 billion for fiscal year 2017 under the 2014 farm bill.

While there is not a specific program that provides for mandatory spending on livestock-specific issues in the agricultural research title of the farm bill as there is for specialty crops, these groups support broad authorizations for publicly funded agricultural research at land grant universities. They recognize the importance of ongoing efforts to identify and address diseases that affect their livestock herds, and will continue to push for expanded agricultural research funding through the annual appropriations process.

By all indications, groups representing both U.S. specialty crop and livestock producers have been reasonably satisfied with how their farm bill programs have performed over the last several years. They are expected to focus on maintaining or even increasing funding for the programs their producers benefit from, especially in the areas of trade promotion and agricultural research.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2006. How Federal Policies Affect Allocation of Water. Publication No. 2589.

Mercier, S.2011. Review of U.S. Farm Programs. Policy background paper commissioned by the AGree initiative.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Risk Management Agency (USDA-RMA).2000-2015. Summary of Business.