In April 2020, a news headline screamed “COVID-19 could wipe out the child care industry in Minnesota” (Orenstein and Schneider, 2020). In September, an article in Time magazine claimed “COVID-19 has nearly destroyed the childcare industry” (Vesoulis, 2021). Like many small businesses across the country, child care providers have faced enormous challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic has also raised awareness of the role of child care as critical infrastructure for the economy. Many child care centers and home-based family child care providers closed or reduced enrollment to meet state or local government guidance for safe-distancing and staying at home,1 especially in the first months of the pandemic. Child care providers who continue to operate face financial challenges due to increased costs and lower revenues. As the country looks forward to recovering from the pandemic, the availability and affordability of child care will play an important role in supporting increased economic activity. Without safe places and nurturing caregivers for young children, employers may be unable to find the workers they need as the economy rebounds. Rural employers struggled with labor shortages prior to the pandemic, and lack of child care was identified as a major rural economic development issue in 2019 (Committee for Economic Development, 2019).

Most parents of young children are in the labor force, and they typically need someone to care for their children while they work. Over two-thirds of children under age six in the United States had all parents in the labor force prior to the pandemic; in Minnesota, the share was 76%.2 The percentage of children with working parents tends to be higher in rural than in urban areas (Swenson, 2008). Many rural families need care for children during evening or weekend hours to accommodate retail and service-sector jobs or shift work. In rural areas, more of the care is provided by home-based providers than child care centers, which may reflect both the needs of rural working parents and lack of economies of scale for centers in places that are not densely populated (Smith, Morris, and Suenaga, 2020). Family child care providers are more likely to provide evening or weekend care, accommodate flexible work schedules, and on average cost less than center-based child care (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2021).

Adequate and affordable child care is important for employers as well as families. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation estimated costs to employers ranging from $400 million to $2.88 billion per state due to child care-related absences and employee turnover (U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation, 2019). With child care and school closures during the pandemic, labor force participation among mothers with young children dropped nearly 4 percentage points between November 2019 and November 2020 (Boesch, et al. 2021). Lost productivity, higher costs, and lower labor-force participation due to lack of affordable and accessible child care options could impede the economy’s recovery from the pandemic.

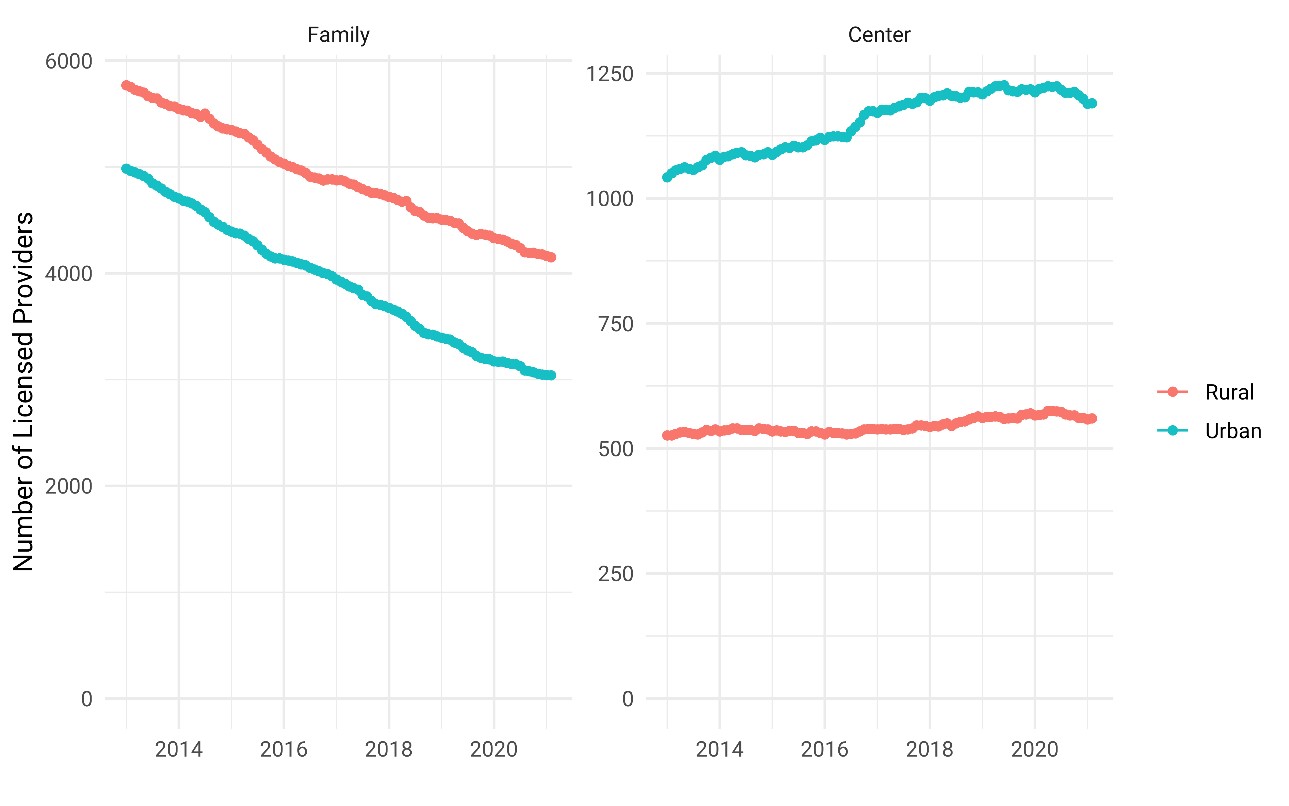

Source: Authors’ calculations based on licensing data.

Child care availability and affordability were known to be critical economic development issues in rural areas prior to the pandemic (Center for Rural Development and Policy, 2017). In 2018, nearly 60% of rural census tracts were defined as “child care deserts” (Malik, et al., 2018), meaning there were more than three children for each space in a licensed child care setting. The shortage of child care in rural areas is related to the decline in licensed family or home-based providers, which fell nationally by 25% between 2011 and 2017 (National Center on Early Childhood Quality Assurance, 2019). The overall capacity of the child care sector (the number of children who can be served) did not decrease, however, as more and larger child care centers have opened. The shift to more center-based care obscures the challenges that many parents, especially those in rural areas, face in finding care (Center for Rural Development and Policy, 2017). Child care accessibility varies spatially within counties and communities (Davis, Lee, and Sojourner, 2019) and some observers consider the lack of child care options in rural areas to have reached crisis levels (Center for Rural Development and Policy, 2017).

In Minnesota, the number of family child care providers statewide peaked above 14,000 in 2002 and has declined steadily since then, falling below 8,000 by 2019 (Minnesota Department of Human Services 2020a). As shown in Figure 1, the numbers of family child care providers have declined in both rural and urban locations in Minnesota while the number of centers has increased, particularly in urban areas.3 Factors contributing to the decline include the retirement of Baby Boomer–age providers, low pay and benefits, and the challenging nature of the work, including limited interactions with other adults and physical demands (Minnesota Department of Human Services, 2020b). The rate of new child care businesses opening has fallen as other careers in the strong prepandemic economy paid better, offered benefits, and presented more advancement opportunities (Minnesota Department of Human Services, 2020a).

In contrast to K–12 school districts, which largely closed school buildings and switched to remote learning, child care facilities were allowed to remain open in nearly all states (although in 17 states they were allowed to care only for children of essential workers) (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020). Despite being allowed to stay open, state agencies reported that nearly two-thirds of child care centers and one-quarter of family child care providers were closed as of April 30, 2020, (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020). Providers who were open faced higher costs due to the increased need for cleaning and sanitizing supplies and personal protection equipment (PPE). One study estimates these factors have raised the cost of providing care by nearly 50% (Workman and Jessen-Howard, 2020). Providers also experienced lower enrollment and changes in group size regulations that limited their revenues and added to their costs (Grunewald, 2020a).

To remain financially viable, the child care business model relies on (nearly) full enrollment. One of the biggest uncertainties currently facing child care providers is when (and whether) their enrollment levels will rebound to prepandemic levels. As of November 2020, a national survey of open providers found that attendance is down by two-thirds, and many child care providers have taken on personal debt or dipped into savings to cover revenue shortfalls (NAEYC, 2020). Under current conditions and without additional funding, one-quarter of centers and one-third of family child care providers predicted they would close in the next few months (NAEYC, 2020). Such closures are likely to exacerbate the child care shortages that existed prior to the pandemic.

From the start of the pandemic, Minnesota has undertaken actions intended to ensure that sufficient child care is available to support the current needs of essential workers and to stabilize the industry for future workforce needs. Minnesota declared child care to be essential and child care businesses were encouraged to stay open. PPE and cleaning supplies were provided. The state quickly granted approximately $41 million to child care providers throughout the state through a competitive grant process (the Peacetime Emergency Child Care Grants).4 The grants were intended to ensure that child care providers could stay in business to support essential workers despite increased operating costs associated with the pandemic (e.g., cleaning supplies and personal protective equipment or PPE). Centers and family child care providers could apply for the grant each month for three months from April through June 2020. About 51% of providers who applied received at least one grant, with the average grant award (summed over the three months) of $8,900 for family child care providers and $29,000 for centers. Beginning in July 2020, the state switched to smaller, noncompetitive grant payments to child care providers; these monthly grants continued through December 2020.5 Overall, the state distributed over $150 million in funding to child care providers in Minnesota between April and December 2020.

To better understand the effects of the pandemic and the grants on child care in Minnesota, we conducted a survey of providers and analyzed data on the number of licensed providers who closed between March 2020 and December 2020. A survey was sent in August 2020 to child care providers who applied for the Peacetime Emergency Child Care Grant program to learn more about how providers used the grant funds and to understand their experiences during the early months of the pandemic.6 Of the 5,297 providers who applied for these grants, 1,898 (36%) responded to the online survey.7

The results of the survey highlight the challenges faced by rural child care providers in Minnesota. Nearly two-thirds of rural family providers and half of centers in rural areas applied for the grants between April and June.8 Most providers reported using grant funds to help pay for cleaning and sanitizing supplies or other health and safety materials. Other expenses paid with the grants included food, utilities, and rent or mortgage. Family child care providers on average reported financial losses of about $4,000 since the start of the pandemic (as of August). Losses were higher for child care centers than for family providers, and larger centers experienced higher losses due to greater losses in revenue. On a dollars per licensed capacity basis, centers in urban areas reported losses of nearly $900 per seat compared to just over $300 per seat in rural areas. About one of every seven child care providers thought it likely they would close in the next six months in both rural and urban areas.

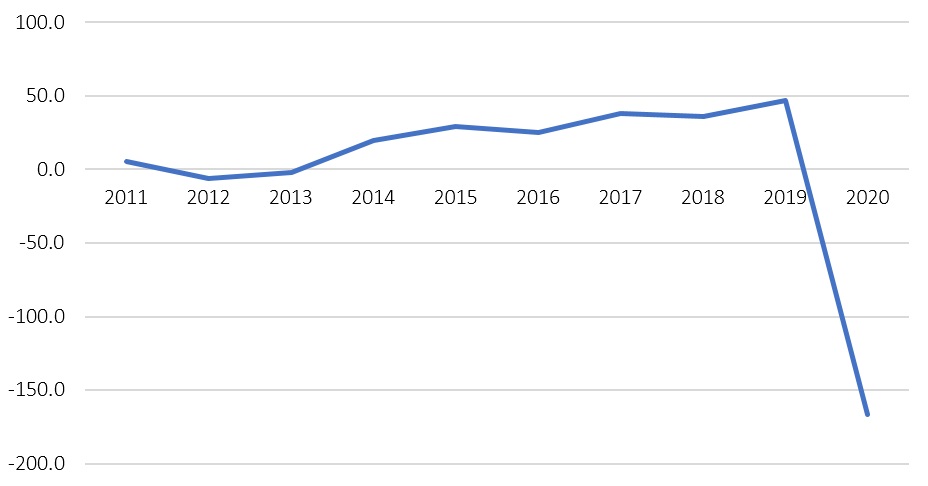

Source: https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/CES6562440001

&output_view=net_12mths.

Despite the pandemic, on February 1, 2021, the total number of licensed child care providers in Minnesota was nearly the same as the number in March 2020, prior to the first stay-at-home order issued by the governor. Undoubtedly, the funding from the state helped to sustain the industry, yet the total numbers open do not capture all of the turmoil and financial struggles experienced by the sector or the challenges that lie ahead, particularly in rural areas. Between March 2020 and February 2021, 404 (9%) of rural family child care providers left the business, and 36 (6%) of rural centers closed their doors. On a more positive note, during the same period, 238 new family child care providers and 28 centers opened in rural Minnesota. While the rate of entry was slower in 2020 than previous years, the ability of new providers to open during the pandemic suggests that the sector has some ability to expand as the economy recovers.

While Minnesota was successful in keeping most licensed child care providers open, many are operating at less than full enrollment and incurring financial losses (Bailey, 2021). As a result, their long-term sustainability is in doubt. As of early February 2021, 60% in Minnesota reported normal attendance levels compared to about half of child care centers nationally (Procare Solutions, 2021). While exact numbers on child care closures are difficult to obtain nationally, the industry as a whole lost 166,800 jobs between December 2019 and December 2020 (see Figure 2). It will be important for states and communities to track changes in the supply of care in rural areas to monitor whether rural supply shortages have worsened.

Supporting the child care sector in dealing with the challenges of the pandemic is likely to have societal benefits greater than for other sectors of the economy. Closure of a child care business, whether home- or center-based, has repercussions for families, employers, and the sector as a whole. Most licensed child care providers receive specialized training and professional development whose costs are partially subsidized with public funding, and closure may mean the loss of this specialized knowledge and experience (the “human capital” of the sector). Families may find it more difficult to find care for their children and may rely on unlicensed care which may not meet basic health and safety standards. Parents, especially mothers, may opt out of the labor force and employers may not be able to find all the workers they need as the economy rebounds. Providing relief funds to child care providers during this period of lower enrollment and higher costs is necessary to avoid worsening child care shortages in rural areas.

Bailey, E. 2021, January 11. “Child Care COVID-19 Response.” Presentation by the Governor’s Children’s Cabinet.

Boesch, T., R. Grunewald, R. Nunn, and V. Palmer. 2021, February 2. “Pandemic Pushes Mothers of Young Children out of the Labor Force.” Minneapolis, MN: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Available online: https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2021/pandemic-pushes-mothers-of-young-children-out-of-the-labor-force.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2021. “Childcare Workers” Occupational Outlook Handbook. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/ooh/personal-care-and-service/childcare-workers.htm [Accessed January 20, 2021].

Center for Rural Development and Policy. 2017. Child Care’s Quiet Crisis: An Update. Available online: https://www.ruralmn.org/child-cares-quiet-crisis-an-update-2/

Committee for Economic Development. 2019. Child Care in State Economies: 2019 Update. Available online: https://www.ced.org/assets/reports/childcareimpact/181104 CCSE Report Jan30.pdf.

Davis, E.E., W.F. Lee, and A. Sojourner. 2019. “Family-Centered Measures of Access to Early Care and Education” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 47: 472–486.

Grunewald, R. 2020a, June 24. “How a COVID-19 10-Person Group Limit Affects Minnesota’s Child Care Providers.” Minneapolis, MN: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Available online: https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2020/how-a-covid-19-10-person-group-limit-affects-minnesotas-child-care-providers.

Grunewald, R. 2020b, October 1. “Surveys Say Inadequate Child Care Options Slow Montana’s Economy.” Minneapolis, MN: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Available online: https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2020/surveys-say-inadequate-child-care-options-slow-montanas-economy.

Malik, R, K. Hamm, W.F. Lee, E.E. Davis, and A. Sojourner. 2020. “The Coronavirus Will Make Child Care Deserts Worse and Exacerbate Inequality.” Center for American Progress.

Malik, R., K. Hamm, L. Schochet, C. Novoa, S. Workman, and S. Jessen-Howard. 2018. America’s Child Care Deserts in 2018. Center for American Progress.

Minnesota Department of Human Services. 2020a. Family Child Care Licensing Trends. St Paul, MN: Minnesota Department of Human Services, Report No. DHS-3746-ENG.

Minnesota Department of Human Services. 2020b. Legislative Report: Status of Child Care in Minnesota, 2019. St Paul, MN: Minnesota Department of Human Services, Report No. DHS-7660B-ENG.

National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC). 2020. Am I Next? Sacrificing to Stay Open, Child Care Providers Face a Bleak Future Without Relief. Available online: https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/our-work/public-policy-advocacy/naeyc_policy_crisis_coronavirus_december_survey_data.pdf.

National Center on Early Childhood Quality Assurance. 2019. Addressing the Decreasing Number of Family Child Care Providers in the United States. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children & Families. Available online: https://childcareta.acf.hhs.gov/resource/addressing-decreasing-number-family-child-care-providers-united-states

Orenstein, W., and G. Schneider. 2020, April 28. “‘We’re Going to Have to Start from Scratch’: How COVID-19 Could Wipe out the Child Care Industry in Minnesota.” MinnPost. Available online: https://www.minnpost.com/national/2020/04/covid-19-could-wipe-out-the-child-care-industry-in-minnesota/.

Procare Solutions. 2021. Tracking the Impact of COVID-19 on the Child Care Industry. Available online: https://info.procaresoftware.com/impact-covid19-child-care-industry-trends-report-ty.

Smith, L., S. Morris, and M. Suenaga. 2020, July 16. “Family Child Care: A Critical Resource to Rural Communities during COVID-19.” [Blog post]. Bipartisan Policy Center. Available online: https://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/family-child-care-a-critical-resource-to-rural-communities-during-covid-19/.

Swenson, K. 2008. Child Care Arrangements in Urban and Rural Areas. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of the Assistance Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Available online: https://aspe.hhs.gov/report/child-care-arrangements-urban-and-rural-areas.

U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation. 2019. Untapped Potential. Available online: https://www.uschamberfoundation.org/reports/untapped-potential-economic-impact-childcare-breakdowns-us-states.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2020. National Snapshot of State Agency Approaches to Child Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Inspector General, Report No. A-07-20-06092, September.

Vesoulis, A. 2021, September 8. “COVID-19 Has Nearly Destroyed the Childcare Industry—and It Might Be Too Late to Save It.” Time Magazine. Available online: https://time.com/5886491/covid-childcare-daycare/.

Workman, S., and S. Jessen-Howard. 2020. The True Cost of Providing Safe Child Care during the Coronavirus Pandemic. Center for American Progress. Available online: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/early-childhood/reports/2020/09/03/489900/true-cost-providing-safe-child-care-coronavirus-pandemic/.

1 Family child care providers, also known as home-based providers, provide child care services in their residences to children who are not related to them. Regulations and licensing requirements for family child care providers differ across states. Here we use the term “child care providers” to include both family child care providers and child care (daycare) centers.

2 Source: Kids Count data retrieved from https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/5057-children-under-age-6-with-all-available-parents-in-the-labor-force. The definition of all available parents in the labor force: For children living with single parents, that parent is in the labor force. For children living with two parents, both are in the labor force.

3 Using the geocoded location of each child care provider and Census definitions, for this report “urban” includes providers located in urbanized areas (population of at least 50,000) and rural includes those located in urban clusters (population 2,500–50,000) and rural areas. The latter two categories were combined into a rural group.

4 For more information about the grants, visit https://www.childcareawaremn.org/providers/emergency-child-care-grants/. Funding was provided through the CARES Act.

5 In January 2021, the state had announced plans to continue funding grants to child care providers through May 2021.

6 The survey was conducted by Child Trends and the Minnesota Child Care Policy Research Partnership. Of the 5,297 providers who applied for these grants, 1,898 (36%) responded to the online survey. For more information, visit https://www.childtrends.org/project/minnesota-child-care-policy-research-partnership.

7 The margin of error for the survey is 2%. We compared the characteristics of respondents and nonrespondents and found some differences. Grant recipients were slightly more likely to respond than those who did not receive a grant.

8 Centers funded by the Head Start program or by local school districts were not eligible for the grants.