Domestic agricultural policy can affect trade and motivate trade disputes. In September 2016, the United States launched a World Trade Organization (WTO) case claiming that China’s yearly government support to producers of wheat, corn, and rice in 2012–15 had exceeded China’s Agreement on Agriculture (AA) commitments. Subsequently, the WTO established a dispute panel for this complaint on January 25, 2017. Assuming this dispute case goes forward, three individuals who are not from the United States or China will be selected to be on the panel, which then will proceed with an assessment.

In WTO disputes, the parties’ arguments are usually not made public until a panel issues its report. To shed light on some of the possible arguments, we examine the key issues at stake in the case China – Domestic Support for Agricultural Producers. A dispute settlement outcome on these issues may be crucial to determining whether the legally effective stipulations of the AA can serve to limit certain kinds of economic producer support. One possible outcome could create pressure on some countries to limit certain types of economic support currently provided or at least employ different policy instruments to deliver support. Whatever the outcome, this case could also strengthen many countries’ motivation to engage—offensively or defensively—in further WTO negotiations on new rules for domestic support that distorts international trade.

Market price support (MPS), which is based on a price gap calculation, is the key component of China’s support to agricultural producers. The MPS measured under the rules of the WTO AA differs from the economic MPS measured by, for example, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). The WTO MPS measurement hinges on several technical terms of the AA, and the panel will likely face related arguments in determining how to measure China’s support. A central point of contention will be the quantity of China’s annual production of each grain counted as eligible for price support. MPS calculations using total production of each grain, and in line with other arguments the United States is likely to make, show China’s support to be above its WTO limits during 2012–15. MPS as measured by the OECD is also relatively high during these years. In this situation, the WTO rules may help rein in the use of certain support instruments and associated economic support levels.

When China acceded to the WTO in 2001, some of its domestic support for agricultural producers became subject to limits that apply to support measured through Aggregate Measurements of Support (AMSs) for individual products. China’s commitments set a de minimis percentage of 8.5% of the value of production as an annual upper limit on each product’s AMS (non-product-specific AMS is similarly limited). A product’s AMS consists of MPS and certain payments.

The U.S. complaint focuses on MPSs for wheat, corn, and rice, though other support may also be challenged (Brink and Orden, 2017; WTO, 2017). MPS is measured under the AA by multiplying the gap between the current year “applied administered price” (AAP) and a “fixed external reference price” (FERP) by the “quantity of production eligible to receive the applied administered price” (Annex 3 of the AA).

China’s WTO accession documents calculate MPS for 1996–98 and state that “Eligible Production for State Procurement Price refers to the amount purchased by state-owned enterprises from farmers at state procurement price for the food security purpose.” The quantity of wheat, corn, and rice procured annually at procurement (administered) prices since China’s accession has been only a portion of total production. China may argue that procurement takes place only in designated regions and only for part of the year and that significant grain production is consumed on-farm and not marketed. Each of these situations reduces the quantity potentially procured at the support price. For corn, which has a different program than wheat and rice, China may also argue that certain purchases are not made at an applied administered price.

The United States, in contrast, may argue that in the absence of a pre-announced maximum procurement quantity, all production of wheat, corn, and rice is eligible to receive China’s announced administered prices. In this view, the announced support price would be the AAP, and it would apply to total production in the MPS calculation.

The panel will have to address these issues to reach a determination in the case. Several questions will arise in interpreting the AA. Article 1 of the AA requires an AMS to be calculated “in accordance with the provisions of Annex 3” and “taking into account the constituent data and methodology.” The 1996–98 calculations in China’s WTO accession documentation, which use procured quantities as eligible production, are its constituent data and methodology. China might argue that its 1996–98 calculations, using procured quantities, are in accordance with Annex 3. A U.S. counter-argument might rest on interpreting the rules in Annex 3 to say that a larger quantity of production should be counted and that the Annex overrides the methodology of the accession document.

The Panel may consider a precedent in assessing these issues. In Korea – Various Measures on Beef, concluded in 2000, the panel introduced the concept of “total marketable production,” a possible opening for China’s argument that grain used on-farm is not eligible for procurement. The WTO Appellate Body (AB), which hears appeals of panel findings on legal grounds, held that “in accordance with” reflects a more rigorous standard than “taking into account.” The AB then reasoned that the quantity Korea had declared it would procure constituted “eligible production” for the MPS calculation, even though Korea actually procured less. This precedent might suggest that if China declared the procurement quantity in advance, this would be the quantity of eligible production for the MPS calculation, even if less were actually procured. It does not, however, clarify a situation in which the quantity to be procured has not been declared.

Calculation of rice MPS faces an additional technical issue. China’s annual domestic support notifications (submitted only for 1999–2010, as of April 2017) calculate the price gap using an administered price of unmilled rice (an unprocessed product) but a FERP of milled rice (a higher-priced product). The United States has asked in the WTO Committee on Agriculture that China use an administered price for milled rice comparable to the reference price. This would make the price gap much larger, since converting the administered price to its milled-rice equivalent raises the price considerably. China’s 1996–98 constituent data and methodology are not explicit on the prices used but seem to have used milled administered and reference prices, which could strengthen the U.S. argument. China’s announced domestic support prices during 1997–98 were only around 70% of the administered prices used to calculate MPS in its accession document, which is close to the conversion coefficient between milled and unmilled rice. The administered prices used for rice MPS dropped sharply in China’s notification for 1999, when unmilled prices clearly began to be used.

If a milled price was used for 1996–98, the United States may argue that taking this into account requires using milled administered prices for rice in 2012–15 and also that this is consistent with calculating AMSs in accordance with Annex 3. China might argue that the requirement to calculate support in accordance with Annex 3 overrides taking into account the constituent data and methodology. Thus, both China and the United States in their arguments might find the AB’s characterization of “in accordance with” as the more rigorous standard to be useful: the United States for eligible quantity and China for applied administered prices. China might invoke the Annex 3 provision for support to be calculated “as close as practicable to the point of first sale of the basic agricultural product” (i.e., for unmilled rice). The Annex 3 provision for adjusting the fixed reference price “for quality differences as necessary” might also be brought to bear when the price observations relate to different qualities, such as milled and unmilled rice, which would favor the U.S. argument for using comparable prices.

Decisions that the WTO has made since 2013 concerning food stock acquisition in developing countries may also affect the assessment of the dispute settlement outcome. Under the heading “public stockholding for food security purposes,” the 2013 Bali Ministerial Decision designed an interim mechanism that essentially allows developing countries with existing support programs to provide unlimited MPS for traditional staple food crops without fear of legal challenge, provided that they meet conditions regarding notification and transparency. A 2014 decision allows the interim mechanism to remain in place until a permanent solution “is agreed and adopted.” The U.S. challenge of China’s support includes years following the 2013 Ministerial Decision and subsequent food stock decisions but seems to be independent of their contents and any arguments China might make under those decisions.

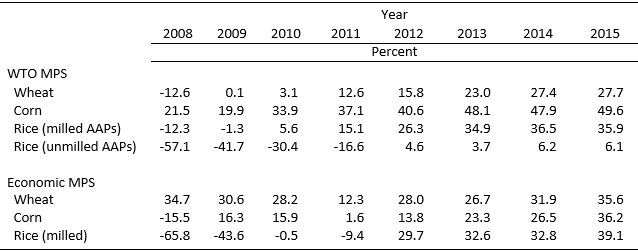

The United States has not made public its MPS calculations by product and year. The upper rows in Table 1 present MPSs (labeled WTO MPS) for China’s wheat, corn, and rice calculated using one possible interpretation of the WTO rules. These MPSs are based on the assumption that the total production of each grain constitutes eligible production, as the United States may argue, rather than any smaller or nil quantities that China may see as eligible production. The MPSs also presume that China’s administered prices are “applied administered prices” under the AA for this eligible total production. The analysis is limited to MPS and does not include any product-specific budgetary AMS components, which have been a relatively small part of China’s AMSs compared to MPS. The MPSs are given as percentages, which makes it easier to see when the nominal limits, which vary from year to year as the value of production changes, are exceeded and relatively by how much.

Sources: WTO MPS: Authors’ calculations; Economic MPS and value of production used to calculate the

percentages: OECD. AAPs are applied administered prices.

During 2012–15, using total production as eligible production and applying China’s administered prices to this quantity, China’s WTO MPSs exceed the limits of 8.5% of value of production, as the United States claims. For wheat they are larger than 15% of value of production in all years and for corn they are larger than 40%. An additional critical factor for rice is the adjustment of the administered prices to a milled basis. The WTO MPSs for rice are as large as 26% or more of the value of production in 2012–15 when the administered price is on a milled basis but are less than the limit of 8.5% using the unmilled rice administered prices. For the preceding period, 2008–11, WTO MPSs for corn are well above the limit of 8.5% in all years. The WTO MPSs for wheat and rice (with milled administered prices) change from negative to positive but exceed their limits only in 2011.

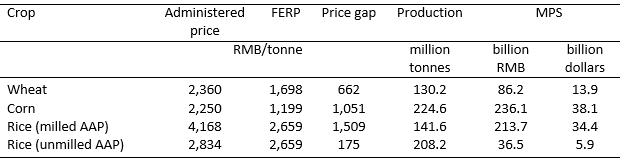

An example of the calculations of nominal values of WTO MPSs is shown for 2015 in Table 2. The WTO MPS amounts in 2015 sum to $86.4 billion, with each crop’s limit exceeded. The limits (not shown) sum to $19.0 billion, resulting in AMSs in excess of the limits of $67.4 billion.

Note: MPS in RMB converted at an exchange rate of 6.2 RMB/$.

The WTO MPSs in the two tables are based on total production, but it is uncertain how a panel or the AB might establish the proper level of eligible production for calculating China’s support. Thus, it is informative to calculate the share of total production of a crop that would generate an MPS large enough to equal its AMS limit. Eligible production corresponding to shares of production less than these levels would, as China may argue, result in AMSs not exceeding China’s commitment. Based on the calculations in Table 1, and depending on the year and crop, eligible production will need to account for at least a range of 17% of total production (corn, 2015, calculated as the 8.5% limit divided by 49.6% MPS using total production) to 54% (wheat, 2012) for the United States to prevail in its argument that China has exceeded its AMS limits, assuming that no other support is included.

While the determination of whether China’s AMSs have exceeded their limits will be made on the legal grounds of the WTO rules, an underlying objective of the AA is to limit agricultural support to reduce distortions in world markets. One measurement of distorting support that arises through policies that affect domestic prices is the economic MPS calculated by the OECD (2016). Economic MPS utilizes the difference between annual observed domestic market prices and contemporaneous border (international) prices. This observed difference results from myriad underlying policies—not only domestic policy instruments but also border instruments such as tariffs, including high over-quota tariffs, and non-tariff measures. The difference, whatever its causes, applies to total output. The economic MPS, which measures the policy-related incentives for producers compared to international prices, contrasts with the WTO MPS, which uses the applied administered price, FERP, and eligible production.

The economic MPSs from OECD are reported in the lower part of Table 1. While specific annual values differ, an alignment occurs during 2012–15: both the WTO MPSs (except rice with unmilled AAPs) and the economic MPSs for wheat, corn, and rice exceed the level corresponding to 8.5% of value of production. Economic MPS is not subject to WTO limits, but exceeding the limit can be considered an indicator of whether economic MPS is relatively high or low.

The instance of the WTO MPS and economic MPS both exceeding 8.5% in 2012–15 is a specific occurrence. In the four preceding years, wheat support in economic terms is at similar levels, but the WTO MPS only exceeds its limit in 2011. If the presumed U.S. interpretation of the WTO rules were to prevail, they could still not have served in 2008–10 to constrain the economic support for wheat. For rice, the WTO MPS also exceeds its limit only in 2011 (with milled AAPs). But, opposite of wheat, rice is a situation where a WTO challenge would not have been motivated on economic grounds in 2008–11, since the economic MPSs shows that rice was disprotected.

The WTO dispute on domestic support was initiated following several years of heightened concerns about market distortions from China’s agricultural policies, even as China has become the top destination for U.S. agricultural exports. Of 20 dispute cases the United States has initiated against China since its accession to the WTO in 2001, only the domestic support case and two others—China – Broiler Products and China – Tariff Rate Quotas for Certain Agricultural Products—exclusively concern agriculture. The United States requested the establishment of a compliance panel in its case against China’s anti-dumping and countervailing duties on U.S. broiler products on May 27, 2016. This dispute traces back to China’s imposition of high duties in 2010 and is one of several issues between the United States and China over such measures, including the imposition in 2016 by China of duties on certain feed imports from the United States, which so far has not escalated to a WTO dispute. The United States requested consultations with China on its administration of tariff rate quotas (TRQs) for wheat, corn, and rice on December 15, 2016. The United States alleges, inter alia, that China does not administer its TRQs for these grains on a transparent, predictable, and fair basis and alleges deficiencies in China’s administrative procedures and requirements. It bears emphasizing that China – Domestic Support for Agricultural Producers is a complaint about compliance with the AA, not adverse effects under the WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Duties, as was the case in the well-known United States – Upland Cotton dispute brought by Brazil. A domestic support complaint under the AA requires the complainant to demonstrate that the respondent has exceeded a limit on certain domestic support but does not require demonstrating adverse effects.

The relatively high levels of China’s economic MPS since 2012 coincide with the possibility that China’s WTO MPSs have exceeded their limits. This raises the prospect that the WTO rules on domestic support may effectively limit certain economic support. To meet its WTO commitments a country would in these circumstances need to limit the amount of economic support, or at least resort to different policy instruments than applied administered prices. In March 2016, China announced that it was modifying its price support program for corn. Lowering or eliminating China’s administered prices for wheat or rice could also be a policy response to reduce future vulnerability to legal challenges. In short, China may itself see merit in an alternative policy direction that relies less on administered prices and MPS.

Reducing the amount of MPS as measured under WTO rules does not automatically reduce economic support. Another possible implication is therefore that the outcome of China – Domestic Support for Agricultural Producers, along with the earlier ruling in the Korea-Beef case, could legitimize a policy landscape in which more WTO members design price support policies specifically to measure only modest support for announced procurement quantities under the rules of the AA without this limitation on the quantity having much effect on the economic MPS provided. The scope of implications from the present case will also depend on the interim WTO decisions taken since 2013 and those eventually given permanent legal effect for food stock acquisition and support measurement in developing countries. In short, the stakes in this case are substantial.

*Subsequent to this article initially being posted, the WTO announced on June 26, 2017

that following agreement of the parties a panel had been composed.

Brink, L., and D. Orden. 2017. “The United States WTO Complaint on China’s Agricultural Domestic Support: Preliminary Observations.” Paper presented at the International Agricultural Trade Research Consortium (IATRC), Scottsdale, Arizona, December 12, 2016, updated January 26, 2017. Available online: http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/253002/2/Session 2 - Brink and Orden Paper.pdf

Matthews, A. 2015. “Food Security, Developing Countries and Multilateral Trade Rules.” Background paper prepared for The State of Agricultural Commodity Markets 2015–16. Rome: FAO. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i5133e.pdf

Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). 2016. Producer and Consumer Support Estimates Database. Country files: China P.R. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/tad/agricultural-policies/producerandconsumersupportestimatesdatabase.htm

World Trade Organization (WTO). 2017. China – Domestic Support for Agricultural Producers, dispute settlement website, DS511. Available online: https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/cases_e/ds511_e.htm